Context

(The) Rhetorical Situation(s)

Students unfamiliar with the rhetorical situation may also find the following longform review of Bitzer's framework helpful.

- Lloyd Bitzer, “The Rhetorical Situation” (1968)

- Richard Vatz, “The Myth of the Rhetorical Situation” (1973)

- Scott Consigny, “Rhetoric and its Situations” (1974)

- Barbara Biesecker, “Rethinking the Rhetorical Situation from within the Thematic of Differance” (1989)

- Mary Garrett and Xaiosui Xiao, “The Rhetorical Situation Revisited” (1993)

- Jenny Edbauer, “Unframing Models of Public Distribution: From Rhetorical Situations to Rhetorical Ecologies” (2005)

Examples of the Rhetorical Situation

- Doss and Jensen, “Dolores Huerta's Shifting Transcendent Persona”

- Palczewski, “The 1919 Prison Special: Constituting white women’s citizenship”

- Cisneros, “Reclaiming the Rhetoric of Reies López Tijerina: Border Identity and Agency in “The Land Grant Question”

- Murphy, “George Bush and 9/11” “Political Economy and the 2008 Election,” “A Time of Shame”

The rhetorical situation is not a single framework, but an ongoing debate about where rhetoric happens, why it happens, and how human communicators are implicated. The successive modification of these theories often is framed as a debate, a back-and-forth between different authors that lead to revised versions of the same theory. If these “debates” typically comprise the substance of an academic literature review, it is important to know how you are either adopting the assumptions of one or another of these frameworks or, alternatively, building upon them to offer something new. It is also important to know what frameworks or assumptions we are not beholden to, so as to define the rhetorical contribution of our work more precisely for a scholarly audience.

The progression of readings on the rhetorical situation offered below was selected for three reasons.

- To offer an overview of the evolution of the “rhetorical situation” debate and how different theorists have made modifications to the theory over time

- To offer the “situation” and “ecology” as two enduring versions of this framework

- To offer examples of these frameworks, specifically, using readings that do not invoke them explicitly.

The point of these examples is to draw attention to how rhetorical critics signal their commitment to the “situation” or “ecology” model even when not citing these explicitly. I also encourage students to consider looking at the introduction of Palczewski’s “1919 Prison Special” as an example of how to scaffold an essay that embraces a rhetorical situation-derived framework.

The term “situation” is significant to rhetorical studies generally because of the way that it tied a theory of rhetoric to a specific set of elements. Written in the decline of neo-Aristotelian rhetorical criticism, Bitzer’s model offered an alternative to rhetorical critics, who could continue to be students of speech and history. Although the rhetorical situation is significant for the genre of rhetorical criticism it yielded (and which is still widely popular today), it is also important for the way that it has stimulated scholarly debate over what can count as rhetoric’s ‘situation,’ which has lead to a number of alternative theorizations. This breadth of approaches covered by these lecture notes models a “conversation” in the field, which here takes the form of a negotiation over the utility of a theory and its necessary modification across a generation of different commitments.

Lloyd Bitzer, "The Rhetorical Situation” in Philosophy & Rhetoric 1(1968): 1-14.

Formula: rhetorical situation →(determines)→ rhetor’s utterance/response

Bitzer defines the rhetorical situation as “the nature of those contexts in which speakers or writers create rhetorical discourse,” or a specialized kind of context that calls a discourse into being. It is “a particular discourse comes into existence because of some specific condition or situation which invites utterance.” The situation “dictates” the rhetorical response in the same way that a question controls the answer, or a problem shapes its solution. The rhetorical situation has 3 elements: (1) exigence (an imperfection marked by urgency), (2) the audience, (3) and the constraints which influence the rhetor’s relationship to the audience.

Why is context ≠ rhetorical situation? Rhetorical discourse is more than a meaning made intelligible by history, and more specific than what occurs in a setting with speaker, audience, subject and purpose (what else is circulating in that moment). To say “persuasive situation” is too general as well. Follows Aristotle (implicitly) to say that there’s an inherent capacity to be persuaded. The rhetorical situation is also not historical context: The rhetorical situation is to historical context as the tree is to the soil it grows from. Just as one cannot predict the tree that will grow from the soil alone, context does not determine the rhetoric of the moment. It’s not just because rhetoric has occurred at a precise historical moment that a situation is rhetorical -- it is because a confluence of three specific elements (exigence, audience, constraint) has yielded it.

What is Bitzer’s Definition of Rhetoric? Bitzer conceives of rhetoric as a spoken address, and defines rhetoric as pragmatic (i.e. as a meaning that can be derived from a specific surrounding context) and in terms of its function to enact action and change. He also states that rhetoric is a mode of altering reality (p. 219) and comes into being because of conditions that require a response. Rhetoric is always a particular utterance or a specific instance of speech, and is organized by the occasion to which it responds. “The rhetorical situation may be defined as a complex of persons, objects, events, and objects presenting an actual or potential exigence which can be completely or partially removed if discourse, introduced into the situation can constrain human decision or action as to bring about the significant modification of the exigence.”

The rhetorical situation’s constituent elements are defined as follows:

- The exigence is “an imperfection marked by urgency,” or the motivating crisis for the rhetorical act. It is located in reality and is objective and observable in public. Not all exigencies are rhetorical because not all crises can be altered through the intervention of a rhetorical discourse. (Imagine screaming into a hurricane) Ultimately, if you can’t modify the exigency through discourse, it’s not a rhetorical exigency. In a rhetorical situation, the ‘controlling exigence’ specifies the audience to be addressed and the change to be effected.

- The audience is circumscribed in a way similar to the exigence. It is not all the auditors present for a speech, but rather only those actors capable of making change. A campaign speech urging listeners to vote reaches far more people than its rhetorical audience, which would include those with rights of enfranchisement and who are not otherwise prevented from voting. By excluding unnaturalized citizens and children, for instance, the rhetorical audience is selectively defined against a backdrop of “mere hearers.”

- The constraints of the rhetorical situation include persons, events, objects, relations that are a part of situation because they have the power to constrain decision making. Bitzer identifies two classes of constraints that fall into the Aristotelian categories of artistic proof (those originating from the rhetor) and inartistic proof (those originating from an external world). Artistic constraints are those originated by the rhetor and their method, whereas inartistic constraints originate from the situation, and are thus outside of the rhetor’s control.

Taken together, the situation the rhetor perceives amounts to an invitation to create and present discourse. (222) Although rhetorical situation invites response, it doesn’t invite any response, but a fitting response. A response that is inappropriate to the situation to which it responds is not rhetorical; to be rhetorical, a response must be prescribed by the situation, it must fit the situation to which it responds: “One might say that every situation prescribes its fitting response, the rhetor may not read the prescription accurately.” (223) Rhetorical situations also exhibit structures which are simple or complex and more or less organized. A strong rhetorical situation is one that is rigorously structured like a courtroom. A weak rhetorical situation is one that is disconnected, scattered, or that has multiple exigencies. Finally, rhetorical situations come into existence, mature, and finally decay, persist, or recur.

Some important distinctions from the Bitzer framework:

- Bitzer’s framework, which remains popular today, was developed out of pragmatist assumptions about language in which the meaning of speech must depend on bounded, contextual features.

- A “context” is not the same as “rhetorical situation,” which is more narrowly defined as the confluence of “rhetorical exigence,” “rhetorical audience” and “rhetorical constraints.”

- “Rhetorical exigence” is (a) an urgency marked by imperfection and (b) is capable of being remedied by means of speech. There are many, many non-rhetorical exigencies.

- “Rhetorical audience” is not the same as the “auditors” or “recievers” of a speaker’s message, but those who possess rhetorical agency, or the capacity to act.

- “Rhetorical constraints” are those ideas attitudes and beliefs that limit what can be said or how what is said may be received. It is not the set of all possible limitations on a speaker, but is similarly bound by concerns of exigence and audience.

Richard Vatz “The Myth of the Rhetorical Situation.” Philosophy & Rhetoric 6 (1973): 154-161.

Formula: rhetor’s utterance/invention →(determines)→ rhetorical situation

If Bitzer argues that meaning is derived from its originating situation, then Vatz argues that meaning is determined by the originating rhetor. This is a reversal of the original claim: whereas Bitzer claims that exigences invite rhetorical utterances, Vatz claims that rhetorical utterances by skilled rhetors create the exigencies to which they appear to “respond”. In his words, “no situation can have a nature independent of the perception of its interpreter or independent of the rhetoric with which he chooses to characterize it.” Because there is always a choice of which situation that a speaker can respond, they can never run out of possible contexts that could define the situation. Information is not only chosen but translated into meaning, which is an interpretive and creative act. The rhetor must, in other words, decide whether or not to make certain features of context salient in their speech. When we see meaning as the result of a creative act and not a discovery, “rhetoric will be perceived as the supreme discipline that it deserves to be.”

Scott Consigny, “Rhetoric and Its Situations” in Philosophy & Rhetoric 7 (1974): 175-186.

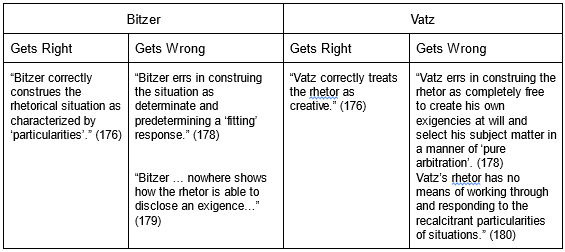

Scott Consigny enters the debate between Bitzer and Vatz as a mediating presence between the extremes of situation-determining-rhetor’s speech and rhetor’s speech-determining situation. He characterizes Bitzer’s position as arguing for an “objective rhetorical situation” that “dominates” and “determines” the rhetorical act, and Vatz’s as “emphasizing the role of the rhetor,” who ultimately creates the situation for their speech. He argues that “Bitzer and Vatz together pose an antinomy for a coherent theory of rhetoric ”and introduces “integrity” and “receptivity” as new concepts which help to bridge this divide. Consigny also argues for a shift away from “situation” and toward “topics” as a broader category for rhetorical analysis.

In response to this diagnosis, Consigny proposes that the rhetor “requires a capacity which allows him to be receptive and responsive to the particularities of novel contexts,” and labels rhetoric “a ‘heuristic’ art, allowing the rhetor to discover real issues in indeterminate situations” on condition of the rhetor’s integrity and receptivity:

- “As an integral art, the art of rhetoric provides the rhetor with ‘integrity’ such that he [sic] is able to disclose and manage factors in novel situations without his action being predetermined.” (180)

- “The art of rhetoric must meet the condition of receptivity, allowing the rhetor to become engaged in individual situations without simply inventing and thereby predetermining which problems he [sic] is going to find in them. (181)

The final move of the essay is to place “situation” under Aristotle’s larger umbrella term of “topics,” which is split into two sub-categories (instrument and realm).

- As an instrument, the “topic is a device which allows the rhetor to discover, through selection and arrangement, that which is relevant and persuasive in particular situations. … The mastery of topics permits the rhetor to enter into and function in a wide variety of indeterminate fields irrespective of subject matter.” (181) [Consigny argues that Bitzer misses this understanding of topic].

- As a realm, “the topic is a location or site, the Latin situs, from which we derive our term ‘situation’. … the ‘place’ of the rhetor is that region or field marked by the particularities of the persons, acts, and agencies which the rhetor discloses and establishes meaningful relationships.” (182) [Consigny argues that Vatz misses this understanding of topic].

Consigny finally proposes that “the two terms of [the] topic” may be treated as “contradictories” (i.e. an opposition in which “one becomes the negation of the other” [situation/speaker; anarchy/totalitarianism (184-5)] or as correlatives [“in which each term is necessary for the understanding of the other.” (185)] “Using topics,” Consigny concludes, “the rhetor has universal devices which allow him [sic] to engage in particular situations, maintaining an ‘integrity’ but yet being receptive to the heteronomies of each case. The real question in rhetorical theory is not whether the situation or the rhetor is ‘dominant,’ but the extent, in each case, to which the rhetor can discover and control indeterminate matter, using his art of topics to make sense of what would otherwise remain simply absurd.” (185)

Barbara Biesecker, “Rethinking the Rhetorical Situation from Within the Thematic of Différance,” Philosophy & Rhetoric 22 (1989): 110-130.

Biesecker enters the debate between Bitzer and Vatz by refusing the determinative logic that either use. Biesecker offers two observations to recalibrate the debate:

- First, Biesecker centers the idea of the text that is transacted from situation to rhetor (and vice-versa). In both cases, the text mediates the identity of the listening subject, which is constituted in a space that is external to the particular rhetorical situation.

- Second, Biesecker characterizes the conventional reasoning of the rhetorical situation as a logic of influence, which assumes a fully coherent subject whose identity is not up for re-articulation. Instead, she proposes (with Jacques Derrida) moving toward a logic of articulation in which a subject’s “fixed” identity is the provisional and practical outcome of a symbolic engagement between the speaker and audience.

Biesecker then turns to Jacques Derrida’s deconstructive reading strategy, which is claimed to be an appropriate way to reframe the Bitzer/Vatz rhetorical situation debate, and which allegedly takes the rhetoricity of texts seriously. As a reading strategy, deconstruction is a way of reading that seeks to come to terms with the way that all language attempts to form unity from existing conditions of division. In the rhetorical situation, this “division” describes the differentiated and contingent subject-positions that are potentially available for an audience.

Placed into the terms of the rhetorical situation, Bitzer and Vatz have equally incorrect understandings of the cause/effect relationship between the rhetorical situation and rhetorical invention. Bitzer sees all rhetoric as an effect structure of the rhetorical situation; Vatz sees the situation as an effect structure of the rhetor’s strategic rhetoric. But even as Vatz rejects Bitzer’s structure, he affirms a larger logic of influence. The underwriting logic of influence presumes that the speaker and/or situation have authority over the text, and that the audience is a sovereign and rational subject. Rhetoric in this context is a mediating force between fixed essences (audience identities) that encounter a variable circumstance (speaker/situation) which exercises control over them. But the fact that this subject seems so stable is an illusion, distracting from the possible subject-positions that rhetoric might activate.

The difficult-to-enunciate difference between the variants of audience that might be produced is ‘différance,’ or ‘difference with an a’. Différance marks an internal and originary division, and has a split definition: ‘to differ,’ or a difference of identity, and ‘to defer,’ or a difference in time or space. Derrida famously deconstructs Saussure and argues that language is neither references a particular underlying concept (a signified), nor does it refer to something primordial that pre-exists the sign system. Any positive value of language is constituted in and against a system of differences, and no element of a sign can function without reference to its difference from others in the sign system. Différance makes the movement of signification (changing meanings, identities) possible and “generates a discourse by a set of differences.” This discourse, the presumptive ‘whole’ of a text or audience, is possible because speech and writing suture and implicit difference that is foundational to language itself. Hence the need for a logic of articulation, which captures the constitution of audience as a temporary displacement of plurality into unity.

Mary Garrett and Xaiosui Xiao, “The Rhetorical Situation Revisited,” Rhetoric Society Quarterly 23 (1993): 30-40.

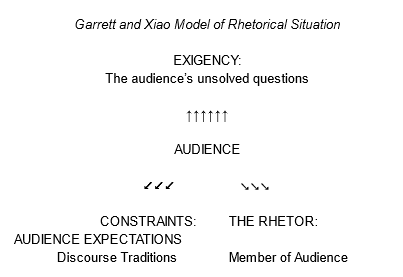

Garrett and Xiao claim that although there have been many theorizations about the rhetorical situation, even Biesecker does not reject the model, but only modifies it. They present a case study based on texts and political discourses from responses to the Opium Wars: “We started out explicating a collection of documents and, in the process, were led to make significant expansions and refinements in the notion of the rhetorical situation” (30) “Chinese themselves came to feel that Chines perception of the exigency presented by the wars lagged behind the historical events themselves.” This delay is now seen to have caused significant political and cultural harm, and their major question concerns the exigency lag. The authors make three major alterations to the rhetorical situation to account for their study:

- “Seeing the audience rather than the speaker as the pivotal elements as an active entity which is crucial in determining exigency, constraints, and the ‘fittingness’ of rhetor’s response.” (30)

- “Recognizing the powerful influence of a culture’s discourse tradition in shaping both speaker and audience perceptions of the same elements” (30-31).

- “Placing much greater stress on the interactive, organic, nature of the rhetorical situation” (31)

The authors are critical of the rhetorical situation because thus far, “much of the early [rhetorical situation] debate revolved around the facticity or “giveness” of the exigency.” The authors also make the claim that theory should be built in response to special cases. The “various improvements and interpretations” of the rhetorical situation “made a valuable contribution in highlighting certain aspects or possibilities of the rhetorical situation, yet none accounted for the complex interactions and nuances of the case we were pursuing.” (32) They adopt what they call the “discourse tradition,” a source and limiting horizon for a rhetor and for the audience of the rhetorical situation. A discourse tradition directly or indirectly participates in the rhetorical situation because it generates needs and promotes audience interests that must be met by new discourses, cultivates an audience’s expectations about the appropriate forms of discourses—subject matter, (38) and affects an audience’s recognition and interpretation of the rhetorical exigency (39). “It might not be going too far to say that, by creating or regenerating needs and promoting interests in an audience, a discourse tradition produces the conditions for its own continuity, recirculation, and reproduction.” (39) The authors then propose a model of the rhetorical situation out of the discourse tradition that suggests that it is possible to keep all three elements in a dynamic tension, and requires seeing AUDIENCE as the active center. The rhetor is usually NOT separate from audience, and rhetorical exigencies are expressions of situational audience’s unsolved: questions, concerns, anxieties,frustrations, or confusions -- all of which may be modified by discourse. Constraints reflect audience expectations for appropriate discourse in those circumstances.

Jenny Edbauer-Rice, “Unframing Models of Public Distribution: From Rhetorical Situation to Rhetorical Ecologies” in Rhetoric Society Quarterly 35 (2005): 5-24.

Edbauer-Rice operates from the assumption that rhetorical situations operate within a network of lived practical consciousness or structures of feeling, and seeks to “destabilize [the] discrete borders of a rhetorical situation.” In this new framework, an exigence should be conceived of within a context of “affective ecologies” comprised of material experiences and public feelings. The theory begins with Michael Warner’s “Publics and Counterpublics,” which (among other claims) critiques the sender-receiver-text model of communication. Edbauer cites Bitzer’s “The Rhetorical Situation” as a productive complication of the sender-receiver model. “This starting point places the question of rhetoric—and the defining characteristic of rhetoricalness squarely within the scene of the situational context.” Although “Bitzer’s theories as well as the critiques and modifications have generated a body of scholarship that stretches our own notions of ‘rhetorical publicness’ into a contextual framework that permanently troubles sender-receiver models,” (7) the rhetorical situation does not account for a situation’s “constitutive circulation.” Drawing upon Biesecker, Edbauer argues that “various models of rhetorical situation tend to describe rhetoric as a totality of discrete elements: audience, rhetor, exigence, constraints, text.” (7) To the contrary, however, “the exigence is more like a complex of various audience/speaker perceptions” there can be no pure exigence that does not involve various mixes of felt interests.” (8) What we dub exigency is “more like a shorthand way of describing a series of events.” (8)

Shifting from rhetorical situation to rhetorical ecology, Edbauer aims “to add the dimensions of history and movement (back) into our visions/versions of rhetorics public situations, reclaiming rhetoric from artificially elementary frameworks.” (9) Rhetoric is a public creation, and offers “rhetorical ecologies” as a substitute for “rhetorical situations.” Whereas rhetorical situations describe the conditions of possibility for rhetoric that responds to a situation, a rhetorical ecology describes the counter-rhetorics that develop between situations. Whereas traditional models of situation depend etymologically and conceptually on the situs, a static, noun-process that fixes locations, the distribution of ecology implies a viral, verb-process in which movement and emotion are central features. “A given rhetoric is not contained by the elements that comprise its rhetorical situation. Rather, a rhetoric emerges already infected by the viral intensities that are circulating in the social field.” (14) If situations-as-situs imply a border or limit, distribution implies affect or ecology of distributed physical, social, psychological, spatial, and temporal elements. If situations-as-situs take place, then distributions imply a process of becoming that involves multiple intersecting actors, locations, and discourses: a place in-process.

Edbauer’s case study investigates how the “weirdness” of “Keep Austin Weird” is distributed through ecologies that expand beyond the traditional boundaries of the rhetorical situation (audience/ rhetor/ constraints). Counter-rhetorics move between individual situations, responding to, resisting, amending an “original” rhetoric. When we temporarily bracket the discrete elements of rhetor, audience, and exigence in the Keep Austin Weird movement, we attend to processes that both comprise and extend those rhetorics.