Nuclear Secrets

This entry (1) introduces major themes connecting the invention and disposal of nuclear materials and (2) deepens the connection between nuclear secrets and ongoing colonialist actions in the United States. The entry (3) ends with a synopsis of a guest lecture by Dr. Kurt Zemlicka of Indiana University, who describes how "deconstruction," a rhetorical reading strategy, can help us to understand the way that language shapes the sciences.

Paired Reading

Peter Galison, "Secrecy in Three Acts"

- How does the institutional management of nuclear secrets anticipate the way that secrets are part of public life in the United States today? What aspects of nuclear secrecy are familiar? What aspects of nuclear secrecy seem specific to the technical or scientific management of secrets?

Nuclear Science and Secrecy

The invention, disposal, and long-term maintenance of hazardous nuclear materials connect us back to themes of secrecy that we discussed previously in the class. There are at least three important connections:

- First that it invokes the idea of institutional secrecy which we discussed early in the class and in this case it really concerns secrecy management of nuclear technologies and the way that institutions that are devoted to developing nuclear technologies have safeguards languages, vocabularies all built up around the idea of needing to preserve security and also in the interest of making sure that secrets are preserved within a hierarchy that they can be maintained authorized disseminated in a controlled fashion. The idea of controlling secrecy in a lot of ways mirrors the idea of controlling nuclear waste because both of these things are things that get out and now suddenly there need to be protocols and all of this structure in order to protect either the literal physical nuclear waste or the metaphorical secret that risks getting out.

- Second, another connection to themes of secrecy and surveillance is the fact that the use and disposal of nuclear materials facilitate the erasure of Indigenous history, lands, and traditions. And in this case, it's a couple of things that are happening. It is first the dispossession of land rights of sovereignty of Indigenous nations but also the removal of traditions and knowledge that specifically reference what it is to these communities that have cultivated over time.

- Third, the metaphors that we use for secrecy and nuclear waste resemble each other. There's a close relationship between them. So metaphors including burial and secretion also refer literally to the actual solutions proposed and enacted to dispose of hazardous nuclear waste. We may talk about burying a secret in the sense of making sure it is locked away completely apart from what we know in public. We may also think about it in terms of a controlled release. Metaphors for secrecy and metaphors for nuclear disposal cohabitate with one another because there’s a close relationship between the way we talk about secrets and the actual practices we use in order to dispose of these hazardous materials. In Comments on the Society of the Spectacle Guy Debord opens with the following passage which is what gets us into the idea of nuclear colonialism, the idea that secrecy the spectacle, and the environmental devastation are closely linked together, and Debord says

The spectacle makes no secret to the fact that certain dangers surround the wonderful order it has established. [And “wonderful” should be read in big scare quotes here.] Ocean pollution and the destruction of equatorial forest threaten oxygen renewal; The earth’s ozone layer is menaced by industrial growth; Nuclear radiation accumulates irreversibly. It (the spectacle) merely concludes that none of these things matter. It will only talk about dates and measures. And on these alone, it is successfully reassuring - something which a pre-spectacular mind would have thought impossible.

The spectacle, which encourages a specific attitude toward secrecy, also encourages people to live with the environmental devastation with the very real risks that are all around them. And in some ways by inoculating the people to the fact that these things are happening they no longer become pressing issues to be addressed immediately urgently. It isn’t that all of these environmental issues are secret but rather that they are leaked into public and that leaking into public is the thing that allows them to creep into our lives without our noticing allows them to be perceived as secrets that pose an ever-increasing risk to human life.

The Rhetoric of Nuclear Colonialism

In the article, "The Rhetoric of Nuclear Colonialism," Danielle Endres makes reference to the following quotation from The Indigenous Environmental Network:

“... the nuclear industry has waged an undeclared war against our Indigenous peoples and Pacific Islanders that has poisoned our communities worldwide. For more than 50 years, the legacy of the nuclear chain, from exploration to the dumping of radioactive waste has been proven, through documentation, to be genocide and ethnocide and a deadly enemy of indigenous peoples … United States federal law and nuclear policy has not protected Indigenous peoples, and in fact has been created to allow the nuclear industry to continue operations at the expense of our land, territory, health and traditional ways of life … This disproportionate toxic burden -- called environmental racism -- has culminated in the current attempts to dump much of the nation’s nuclear waste in the homelands of the indigenous peoples of the Great Basin region of the United States.”

One example is the Hawaiian Island of Kahoolawe which is a nuclear test site conducted by the US government during World War 2. The government dropped a tremendous amount of nuclear "ordinance" on top of this island, a sacred site for the Indigenous peoples of Hawaii, and effectively cracked the water table so that it is uninhabitable at this point and now is a reserve or a preserve but effectively cuts off access to Indigenous lands.

According to rhetorical theorist and critic Danielle Endres, the rhetoric of nuclear colonialism refers to "a system of domination through which governments and corporations target indigenous peoples and their lands to maintain the nuclear production process" (41). It is a process that relies upon ignoring the land ownership rights of colonized peoples, and which uses the legal and political system to limit their rights. It is also a process that uses the colonizer's language and rhetoric to justify the colonial project while enabling colonizers to escape the experience of shame or guilt for having perpetrated historic and present-day harms. As Endres notes, "approximately 66 percent of the known uranium deposits are in reservation land, as much as 80 percent are in treaty-guaranteed land, and up to 90 percent of uranium mining and milling occurs on or adjacent to American Indian land.” (41)

Endres attends to the Yucca Mountain facility, which is embedded into the landscape. Images of this site include is a system of tunnels a network of tunnels that literally puts the nuclear waste out of sight. Rhetoric takes the form of justifications, strategic silences, and official practices of naming that allow this project to continue. The effect is to dispossess the Indigenous peoples who occupy these territories of their rights of land sovereignty.

The rhetoric of nuclear colonialism reinforces resource colonialism, which “depends upon ignoring the land ownership rights of the colonized [and] relies on the country’s legal and political system to limit the rights of the colonized ...” (43) It is “the language used by colonizers which acts as a crucial justification For the colonial project.”(44) They set up a “vast justification system that allows the colonizers to prevent themselves from feeling guilty”(44). The rhetoric justifying the Yucca Mountain facility and the rhetoric of nuclear colonialism generally are manifestations of colonialism. Included in these are legal practices of naming that reduces the status of Indigenous nations to a lesser status than the American federal government:

“This strategy names American Indian nations as part of the US public by denying government-to-government negotiations, forcing participation in the public comment period and describing all opponents as public critics. This simultaneously deflects the sovereignty of American Indians and hails them as assimilated members of the US public, resulting in the rhetorical exclusion of American Indians from the public comment period. Furthermore, forcing American Indians to participate in the public hearings also serves to exclude their arguments about land rights, sovereignty and government-to-government negotiations because, as discussed above, current models of public participation excludes non-scientific arguments. Although American Indian nations had asserted their land rights and political sovereignty in the public comment period, they and their arguments were rhetorically erased by a discourse naming them part of the US public. (50)

Because Indigenous nations because American Indian nations were only really allowed to intervene during a “ public comment,” that act of naming alone relegated them to “the public” because it cut off their ability to wager arguments that work otherwise considered to be not legitimate or not scientific. It also dismissed their sovereignty. The way that we name peoples and allow their own participation under certain headings is exactly how persuasion communication happens because it sets the stage for the kinds of debate that can occur. And even though there is any mention of secrecy specifically the article does address these practices such as silencing and naming to talk about the argument tactics of deflection that are used by representatives of the US government The last thing that I wanna talk about in this article, in particular, is the sort of larger feel in which this rhetoric is set or the way that this rhetoric address more than just the Yucca Mountain controversy but areas topics territories that are well beyond it.

“By 2035, there will be approximately 119,000 metric tons of high-level nuclear waste (well above the 77,000 metric ton limit) at the Yucca Mountain site. 51 In anticipation of the current waste crisis, Congress passed the Nuclear Waste Policy Act (NWPA, 1982, amended 1987), which vested responsibility with the federal government for permanently storing high-level nuclear waste from commercial and governmental sources, The NWPA provides an immense subsidy for nuclear power industry because it stipulated that Congress assume billions of dollars of financial responsibility for nuclear waste storage. In 2002, the Secretary of Energy, the President, and Congress officially authorized the Yucca Mountain site as the nation’s first high-level nuclear waste repository. The site authorization was widely opposed by Westerrn Shoshone Paiute nations who claim treaty-based and spiritual rights to the land.” (47)

But at the same time, this is sort of kicking the door wide open right? And that’s the step that takes us to other nuclear waste sites and the problems of nuclear colonialism that aren’t just inclined to the Yucca Mountain site but are certainly included.

The Erasure of Indigenous Fossil Knowledge

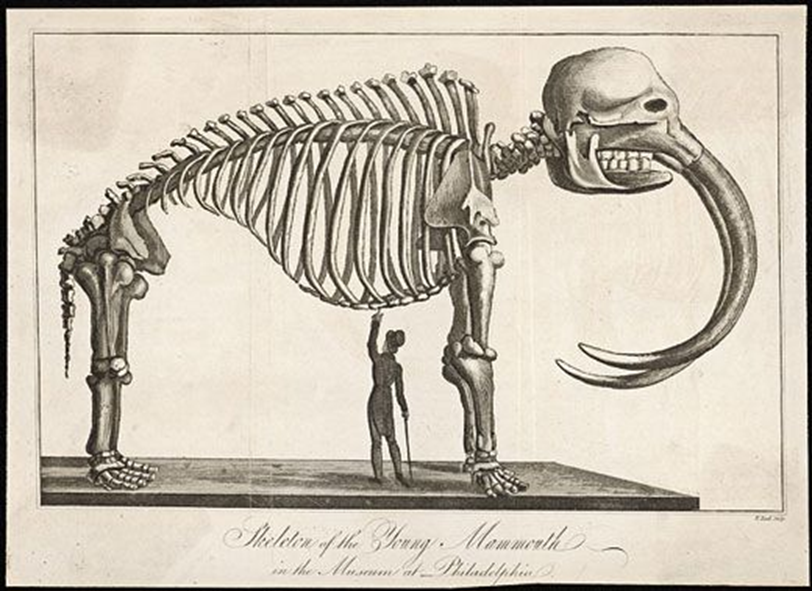

The chapter "Suppression of Indigenous Fossil Knowledge" by Adrienne Mayer describes Evangelical Christian encounters with an Indigenous fossil record. Mayer argues that Indigenous knowledge was simultaneously informative for evangelical settlers and deemed untrustworthy. It describes how language and its discourse facilitate acts of erasure. Mayer for instance describes the enactment of erasure in her description of Cotton Mather:

In his (1712) letter to the Royal Society, [Cotton] Mather argued that the bones belonged to a giant victim of the flood. This and similar finds in North and South America were ‘scientific proof’ that giants had once inhabited the Americas and died when the flood inundated the whole world. To support these claims, Mather referred to local Indian lore. ‘Upon the Discovery of this horrible Giant,’ Mather wrote, “the Indians within an Hundred Miles’ maintained that giants were described in their ancient traditions, passed down over ‘hundreds of years.’ For example, among the Albany Indians, ‘continued Mather, the giant’s name was Maugkompos.’ But Mather suddenly breaks off to ridicule Native AMerican languages, with their ‘disagreeable’ sounds and ludicrously long names. He digressed to spell out a long Algonquian word of fifty-four letters, with a jocular aside to the poor printer who has to set the line of type. Mather dismisses the topic abruptly: ‘There is very Little in any Tradition of the Salvages [sic] to be relied upon.

You can see the two gestures of erasure happening: there’s this reference to indigenous knowledge then completely dismissal of that knowledge in favor of Mathers Scientific but also a deeply religious account of the event. Additionally, the article draws attention to the need for ignorance The need for leaving fossil sites alone and at the end of the article Mayor draws attention to the following:

“Many Native American groups traditionally believe that fossils contain powerful ‘medicine’ or magical forces for good or ill. Some fossil traditions are sacred, secret knowledge, which should not be made available to the uninitiated or vulnerable or to outsiders. I have participated in maintaining this kind of ignorance: in interviews on reservations. I promised not to publish new oral fossil knowledge unless something similar had already been published. Some knowledge of fossils is not just withheld from outsiders but within the tribe. Collection of large animal fossils or attempting to obtain power from them is forbidden in some native cultures. For example, many traditional Navojos avoid touching or talking about anything to do with death, including dinosaur fossils in their lands. In the fossiliferous West, many Plains Indian groups traditionally avoid disturbing petrified bones. ”

The Waste Isolation Pilot Plant (WIPP)

The WIPP is a nuclear waste disposal site similar to the more infamous Yucca Mountain site. Across the American Southwest in the late 20th century, American Indian nations were targeted for temporary waste storage through the now-defunct Monitored Retrievable Storage or the MRS program. A proposal by the private fuel storage and Skull Valley Goshute to temporarily store nuclear waste at Skull Valley go to the reservation was defeated by activists working with the state of Utah. But this hasn’t stopped the US government from continuing to set up nuclear storage sites specifically on indigenous land and most especially on the US Mexico border which is where we find the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant in New Mexico.

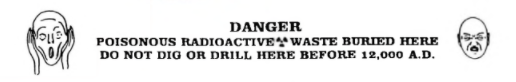

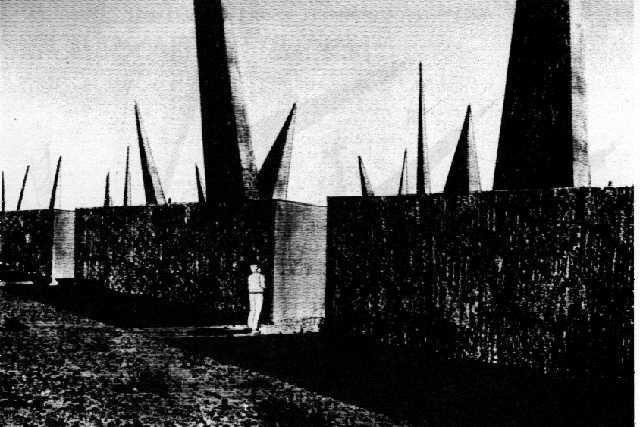

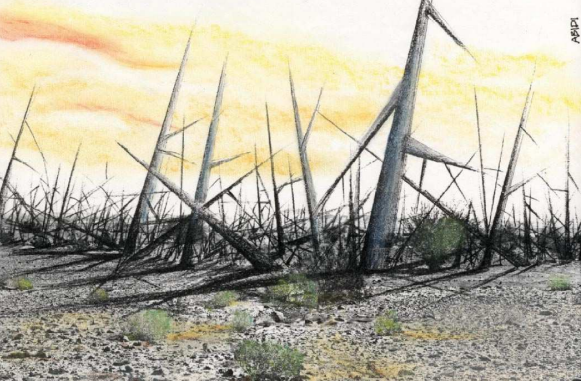

The WIPP is the world's 3rd deep geological Repository licensed to store transgenic radioactive waste for 10,000 years. Which is significant. 10,000 years is approximately the entire length of available, recorded human history. The plant started its operation in 1999 and the project is estimated to cost $19 billion in total. The WIPP has been disposing of legacy transuranic waste since 1999 claiming up to 22 generator sites nationwide. The WIPP was constructed for, according to the government's own website, the disposal of the defense-generated TRU waste from DOE sites around the country. Transuranic radioactive waste contains consistency of clothing tools, rags, residue, debris, soil, and other items contaminated with small amounts of plutonium and other man-made radioactive elements. It is disposed of in rooms mined in underground salt at a layer of over 2000 feet from the surface. So it is very deep underground and if you were to encounter it would look somewhat familiar: it would just look like ordinary, banal objects saturated with radioactive waste. The WIPP is located approximately 26 miles east of Carlsbad, New Mexico. In an area known as the Southeastern New Mexico Nuclear Corridor which also includes national enrichment facilities near Eunice, New Mexico. The waste control specialist low-level waste disposal facility just over the border near Andrews Texas and the international isotopes facility to be built near EuniceNew Mexico which may also already be in existence. The storage rooms are again 2150 feet underground in a salt formation.

There are a lot of details here about how this came to be: it was authorized in 1979 when Congress redefined the level of waste to be stored in the WIPP from high temperature transuranic or low-level waste. This waste consists of items that have been saturated with Plutonium or uranium radioactive radiation. This includes gloves, tools, rags, and machinery. Construction remains costly and complicated. In November 1991 a judge ruled that Congress must approve WIPP before any waste even for testing purposes in the facility. This indefinitely delayed testing until Congress gave its approval which led to a large amount of deliberation about how it was that the waste was to be stored as well as how to communicate this message that the waste was going to be stored for the period that it will remain radioactive.

The final legislation demanded that the EPA or the Environmental Protection Agency issued a revised safety standard facility and required the EPA to approve testing plans. The first extensive testing was in 1988 and yet it did not actually start until 1999. Then in 2014 mishaps at the plant property brought focus to the problem of what to do with this backlog of waste and whether or not the WIPP would be a depository. The 2014 incident involved a waste explosion and an airborne release of radiological material that exposed 21 plant workers to internal doses of plutonium. The radioactive material leaked from a damaged storage truck but it also begs the question of whether any of the deliberations that happened in the 1990s was sufficient in order to actually protect the material there because given that it was supposed to last as long as it was the period of 15 years it’s not that much. And so the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant provides an important case study for thinking about how it is that nuclear colonialism perpetuates itself and how this rhetoric of well we are completely protected or well there is this susceptible level of radiation or well this is the way that we’re going to build a rhetorical perimeter around this facility how all of these efforts are liable to come apart.

In Comments on the Society of the Spectacle Debord talks about how the standards for nuclear waste or for nuclear waste disposal or not nuclear waste disposal actually maintaining of the facility that Produces nuclear energy changed over time.

“In June 1987, Pierre Bacher, deputy director of installations of Bectricte de France, revealed the latest safety doctrine for nuclear power stations. By installing valves and filters it becomes much easier to avoid major catastrophes like cracks or explosions in the reactors, which would affect a whole ‘region’. Such catastrophes are produced by excessive containment. Whenever the plant looks like blowing, it is better to decompress gently, showering only a affected area of a few kilometres, an area which on each occasion will be differently and haphazardly extended depending on the wind. He discloses that in the past two years discreet experiments carried out at Cadarche, in the Drome, clearly showed that waste - essentially gas - is infinitesimal, representing at worst one percent of the radioactivity in the power station itself.’ Thus a very moderate worst case: one per cent.”

But one percent doesn’t communicate a lot in that number it doesn’t give us the sense of how likely it is that someone would develop cancer how likely it is that some people would be contaminated or how wind fluctuations can change this equation entirely

“Formerly, we were assured there was no risk at all except in the case of accidents, which were logically impossible. The experience of the first few years changed this reasoning as follows: since accidents can always happen, what must be avoided is their reaching a catastrophic threshold, and that is easy. All that is necessary is to contaminated little by little, in moderation.”

And to be clear and I want to be very direct about this, Debord is not endorsing this but this is the way that the rhetoric of nuclear Colonialism, how secrecy and the atom prolong themselves. And we only find out about the effects of these belatedly after the fact after the standards are revised or after something like what happened in 2014 at the WIPP happens after the procedures that are set up just do not succeed.

Dr. Kurt Zemlicka: On Deconstruction and the Sciences

Deconstruction is a reading strategy that looks at binaries, and what it wants to do is show how it underpins or explains something taken-for-granted in the world, like the distinction between humans and animals. Let's start by thinking about the “why” of deconstruction. What’s the point? The thing that deconstruction does is that it makes simple things stupendously complicated. It’s difficult because making something obvious difficult to follow, there has to be a payoff. The utility is that by making simple things complicated, it allows us to think about discourse in a new way. We can explore their potential difference and how they could be as opposed to how they are.

Deconstruction points out how that binary is both false and necessary. We intuit that there is a difference between humans and animals, but we don’t necessarily draw attention to the “bright line,” the firm distinction between them. The concept of human and animal don’t have positive meaning -- they are defined negatively or against one another; animals as not-human, humans as not-animal. So the distinction between the two is arbitrary. What you cannot do, then, is that you cannot say that we “privilege humans too much, and so we need to prioritize animals instead!” You can’t just say that there is a term that is dominant and another that is not, and we need to ‘flip’ and end of story. That reinstalls a similar problem at a different level.

Let’s talk about deconstructing the binary between OBJECTIVITY and SUBJECTIVITY, particularly as it relates to science. We intuitively know that the difference between the sciences and the humanities is that the former is more objective than the latter. We somehow relate objectivity to what it is that the sciences ‘make’ or ‘produce.’ A natural law apparently exists independently of our ability to perceive it. Gravity is gravity under all circumstances. If there is any type of subjectivity there, then it would break the ability of science to make the kinds of claims that it does.

In the context of teaching “the rhetoric of science,” this phrase often connotes to people that you’re reducing all science to a subjective perspective, where everything is relative and nothing is stable. Objectivity aims to purge notions of subjectivity, position, and point of view from itself; and so there is the bright line of objectivity as defined as not-subjectivity and vice versa. And this distinction is policed or patrolled because of the fact that it makes advocacy for science possible, and it safeguards the authority/ethos of objective scientific practitioners.

How does science announce its objectivity? The way that science is communicated is different than humanities, English, and Communication philosophy is communicated. Experiments are typically this difference, independent/dependent variables interact and they produce or yield some consistent set of results, which once repeated, point to a natural law. Knowledge needs to be communicated; to share knowledge about something.

- Constative: what it says (“the literal or denotative function of knowledge/language”)

- Performative: how it says it (“how knowledge is stylized as a recognizable article format”)

If the goal of an experiment is to make an observation about something specific and then infer a natural law from that observation, anyone who has taken a basic logic class would know that’s not possible. Hume’s inductive fallacy and the example of the billiards table is the reason: you cannot combine any number of specific instances to predict what happens in the future. Moving from the specific to the general is impossible because there is no guarantee that we move from the specific to the general.

“If it is raining then the grass is wet” is another example. If we start with the general principle and then move to a specific example. But you can’t move the other way: “the grass is wet,” therefore “it is raining” is bad reasoning. Even if there are a billion instances of that happening, it’s still not a natural law.

The constative element of an experiment is contradicted by its performance; the individual experiment is intended to -- but can’t -- prove a natural law. You’ve then flipped the binary, but you haven’t shown us what the value is, you may even have done more harm than good in this instance.

Any kind of communication has to have a subjective element. Objectivity is subjectively constructed or built. It is communal and commonly built. Scientific articles today are very different from those in the past. Our standards for objectivity change over time because that objectivity is always performed or enacted. So

- (1) Scientific objectivity is subjectively constructed.

- (2) Science is subjective and yet

- (3) it is the most objective thing that we have.

Science is the only form of knowledge that we know can produce natural laws. We cannot abide by a merely subjective understanding of science because we still need to communicate the realities of, for instance, pandemic disease, war, and climate change.

On a broader level, what analysis like this shows us is that the relationship between deconstruction and politics is more than navel-gazing. What you do with this means that deconstruction ‘itself’ isn’t a political act, but because it allows us to open a space for thinking otherwise and therefore acting differently. There is something that is closed off when we think uncritically in terms of binaries. In that contingency, there is the possibility of politics. That’s why deconstruction and rhetoric go well too -- the upholding of binaries in discourse relies on performative -- that is rhetorical -- acts. That is the mechanism for us to think about what it is that we can do once we’ve moved through the deconstruction. That’s the usefulness of the idea of “impossible but necessary,” or “false but necessary” thinking. Rhetoric takes things that are simple and complicates them. When we look at discourse, we want to as rhetoricians show how the modes of persuasion are operating, not that there is an objective format for communication but that it is an ongoing process of meaning-making. That’s why deconstruction isn’t navel-gazing, but a possibility of thinking otherwise about a topic.

Additional Resources

- Peter C. van Wyck, Signs of Danger: Waste, Trauma, and Nuclear Threat

- Calum Matheson, Desiring the Bomb: Communication, Psychoanalysis, and the Atomic Age

To Cite This Page

- Atilla Hallsby (2022), "Nuclear Secrets" in The UnTextbook of Rhetorical Theory: The Rhetoric of Secrecy and Surveillance. https://the-un-textbook.ghost.io/secrecy-and-surveillance-nuclear/. Last Accessed (Day Month Year).