The Police and The Detective

Paired Reading

Sarah Brayne, "Policing By Numbers"

The Police

- This section of the entry was assembled with assistance from undergraduate student and RA Dani Follett-Dion in Spring 2022.

In this class, "the police" describes those who monitor, surveil, and wield the state's "monopoly on violence." During and before the Civil Rights movement, the police worked to eliminate the ‘threat’ of communism and, by turning their gaze upon rights-seeking Black Americans, intensified anti-Black violence and deepened existing racial inequalities.

One prominent example of this kind of policing is presented by the Federal Bureau of Investigation's (FBI) pursuit of Martin Luther King Jr. in the 1960s and 70s. Following King’s involvement with the Montgomery bus boycott in December 1955, the FBI began monitoring him with the belief that he was connected to the communist party, particularly because of his ties to Stanley Levison, who allegedly maintained deep ties to communist Russia. King’s ability to mobilize the population as the president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) marked him as a danger to social order, despite his preaching of nonviolence in protest strategy. As Levison stood as an advisor to King, the FBI increased their surveillance, wiretapping Levison, Clarence Jones, and others who were closely connected to King. In the wiretapping of Jones’ home, the FBI discovered evidence of King’s marital affairs. It became imperative to J. Edgar Hoover, FBI director at the time, to gather evidence of King’s flawed personal life and use it to paint King as a liar. Once the authority was given to the Hoover-led FBI by the attorney general, Robert Kennedy, to wiretap King’s private life, they relentlessly pursued space to exploit King’s extramarital relations in order to contain the growing movement. Throughout this time of social unrest, the FBI worked to break apart organizations within the movement, particularly with the establishment of counterintelligence programs.

The COINTELPRO counterintelligence operation was subsequently used by Hoover and the FBI to undermine and disrupt related organizations which were widely depicted to white Americans as threats to national security. In 1967, Hoover’s initiation of the COINTELPRO-Black Nationalist Hate Group program began targeting Black activist organizations that merely posed a potential for inciting violence and uprising among Black communities, including Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), the King-led Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), and the Black Panther Party. Within this strategy to monitor and control these groups, the FBI also worked to conceal itself from other offices, their targets, and the public, particularly through anonymous communications.

Of course, the FBI was unable to fully conceal its covert and clandestine operations from the public. While questions of King’s sexual exploits came to light, Hoover’s own sexuality also came into question. Hoover was working tirelessly to uncover the secrets of Black-organized movements, but he was doing the most work to hide his own, as he led the FBI during a time of panic around homosexuality. Moral panic about sex crimes along with attention to sexual indiscretion, were tools used to redirect attention away from himself and back toward the public.

** sections below are intended for a future version of this class. The videos below are excellent and informative, and have direct tie-ins with "the police." Prospective (future) topics include omnipresent policing and lantern laws **

Omnipresent Policing

Prof. Simone Browne speaks at MozFest 2016 about surveillance and race online.

@marciahoward38thstreet Fuckery afoot. Salt-lick stolos. #nogozone #fyp #teacher #grandtheftauto #foryoupage #justiceforgeorge

♬ Taste It - Ikson

TikTok video by Marciahoward38thstreet documenting a police "salt lick" at George Floyd Square in Minneapolis, MN.

Lantern Laws

Dr. Simone Browne's "Acrylic, metal, blue, and a means of preparation: Imagining and living Black life beyond the Surveillance State." Presented during Microsoft Research's "Race and Technology" Lecture Series on October 27, 2021.

- "Lantern Laws were 18th century laws in New York City that demanded that Black, mixed-race and Indigenous enslaved people carry candle lanterns with them if they walked about the city after sunset, and not in the company of a white person. The law prescribed various punishments for those that didn’t carry this supervisory device. Any white person was deputized to stop those who walked without the lit candle after dark. So you can see the legal framework for stop-and-frisk policing practices was established long before our contemporary era." (Simone Browne, "The Surveillance of Blackness: From the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade to Contemporary Surveillance Technologies," Truthout March 3, 2016)

Policing in Critical and Cultural Theory

The police are also a prominent feature of late 20th century critical theory, where they represent not only a state monopoly on violence but also the use of language as a technique of social control. Frantz Fanon and Roland Barthes, for instance, describe the European colonial government as a "policing" force that uses ideologically-motivated images and messaging in order to persuade a mass public – both European colonizers and those African peoples who have been colonized – of the moral superiority of colonialism as a political and war-making project. Among the most famous cinematic depictions of this colonizer/colonized dynamic is the film The Battle of Algiers, which tells the story of colonial France's military incursion into Algeria and the resistance to it.

There are many other examples of "policing" as a core aspect of critical and cultural theory. Louis Althusser's example of "interpellation" is of a police officer hailing a passer-by on the street. Literary theorist Mikhail Bakhtin wrote about the polysemic qualities of language using the example of the police, stating that language may be so esoteric and specific for an 'in-group' so as to be undetectable in public, thereby avoiding the secret police. Both the Russian Bakhtin and German Walter Benjamin were apprehended by secret police in their lifetimes, leading to the former's exile and the latter's suicide. Among Antonio Gramsci's most famous works are "the prison notebooks," where he theorizes the force of hegemony in the twilight of fascist Italy. Michel Foucault, who is often credited with developing important concepts about the role of surveillance in contemporary culture, actively and prolifically wrote about prisons, asylums, and other policing institutions. In the United States, abolitionists like Angela Davis and Joy James have written extensively about mass incarceration and emancipation. All of these examples illustrate the centrality of policing and carcerality to the contemporary critical theory tradition, even if it is not often understood as central to theories of language, power, and government.

Here are some examples of this kind of theorizing, described in greater detail:

In Society of the Spectacle and Comments on the Society of the Spectacle: Treatise on Secrets, Guy Debord encourages us to think of the police in terms of ...

- An international, and not a local, scale of enforcement. The rhetoric of the police is one that disguises itself by being on the move in terms of the agencies and acronyms which are the centralized locus of enforcement.

- As always engaged in “preventative civil war,” in which the police are the state’s only authorized arbiters of violence, which they justify by reference to a perceived threat of violence. This also means that the violence that is prevented often has not occurred (i.e. “pre-emptive police violence”) but the alleged immediacy of the threat justifies brutality.

- As both an institutional affiliation and as a mindset or psychology. Post-structuralist philosophy is not exempt, and there is evidence that even this kind of thought has been under institutional surveillance.

According to Ersula Ore in Lynching: Violence, Rhetoric, and American Identity, rhetorical policing consists of (among other things)

- the argumentative tactics to “save face” and the “denial of lynching’s adaptive and transformative nature.” This includes but is not limited to the narrow signification of words like “murder” and “lynching” as well as an insistence upon small formal differences and not the overt motive.

- “Specific to this analysis is my rhetorical deployment of the term murder. Although the legal definition of murder varies from state to state, murder is generally understood as the unlawful killing of a person with intent, malice, and/or premeditation. While I cannot ignore the legal definition, I do resist that this narrow frame is all the term can hold.”

- “[N]arrow definitions for what constitutes a lynching permitted conservatives to deny the continuity between Trayvon and Emmett’s slayings and to conclude that those who read Trayvon and Emmett as 'the same thing' were more interested in stoking the fires of racial division than in encouraging racial unity.”

Finally, the theories of Frantz Fanon (1952) and Louis Althusser (1970) provide two similar accounts regarding the way that policing is a practice of naming. The core similarity between these theorists is that they describe rhetorical naming as a kind of policing.

- Fanon, a Martinique psychiatrist and anti-colonial thinker, describes the experience of walking down the street in a colonized territory and the way that naming is the repetitive and repressive experience of being positioned within the white colonizer’s gaze.

- Althusser, whose major theoretical framework is rooted in principles of labor power and exploitation, explains the concept of “interpellation” as a situation in which the police call out “hey you” to someone who is standing on the street, and the (mis-)recognition of this hail constitutions a mode of subjectivation, or an internalization of identity as a position that is subordinate to ideologically-enforced state power. One becomes subject to the state by responding to the hail, by recognizing oneself as the subject of the hail even before it is clear that they are the ones being addressed by it.

It is noteworthy that Althusser’s generalized theory of interpellation (anyone may be subjected to state power) is often (perhaps unnecessarily) prioritized in scholarship over Fanon's situated and semi-autobiographical critique of colonial power. Fanon's unique contribution is not a theory of "the" subject who is policed, but rather the understanding that not all subjects are equally subjugated.

Detective Fiction

Detective fiction is a literary genre or style of storytelling that helps us to understand why the practices of policing, most forgivingly called “detection,” have infiltrated public and popular culture. Detective fiction promoted secrecy as a kind of common sense about the way that the world worked because it created a narrative in which, for instance, the reader encounters the mystery as they are the “detective” who deduces or stumbles upon it. Resolution of the “detective” story relies upon a demonstration of how the inconspicuous details given at the beginning of the story allow the protagonist to pin-point the perpetrator of the crime or the location of a secret document, using primarily their logic. Less noticed but no less important is the way that detective fiction put the reader into the position of the detective. As English philosopher Thomas Hobbes puts it in the 1651 Leviathan, modern public law is founded on the idea that the state has a monopoly on violence. By fostering identifications between the popular reader and the detective protagonist, the door was opened for those publics to imagine themselves as executors of the law, called upon to be watchers on behalf of the state, in their everyday lives.

The “origin” of detective fiction is often attributed to the emergence of this style of novelistic writing in the 1800s. It was unique because it placed the “scientific” faculties of Enlightenment reason in the hands of the detective-protagonist, and the main characters of such narratives tended either to be police or worked alongside them. Edgar Allan Poe’s 1844 The Purloined Letter, for instance, tells the story of a palace scandal, in which a secret letter received by a Queen is stolen by a crafty minister. The detective of this story is Auguste Dupin, who Poe interestingly calls an “analyst”. Dupin finds the letter using probability and deduction, and which he compares to a childhood game of marbles, similar to “paper-scissors-rock.” Arthur Conan Doyle, writing at end of the 19th century, similarly establishes the detective as the counterpart of the police. His character, Sherlock Holmes, embodies a perfection of scientific observation and deduction who both works on behalf of the same legal apparatus as the police, embraces a procedural view of the law and its use of violence -- and, by performing the police's task more expeditiously than the police themselves, makes them appear foolish.

Scene from Season 3, Episode 3 of "Columbo," "Candidate for Crime."

Detective fiction is still organized around conventional plots and characters that create a familiar experience of tension, expectation, and desire. As literary theorist D.A. Miller explains, the genre of detective fiction lends the secret a predictable beginning and end: “Though the detective story postulates a world in which everything might have a meaningful bearing on the solution of the crime, it concludes with an extensive repudiation of meanings which simply ‘drop out’.” The secret always takes the form of “ordinary, ‘trivial’ facts” or “’telling’ details” that are inconspicuous until the right configuration of characters and testimony has been revealed. Detective fiction is like stumbling upon a password without knowing the encryption key, and the story is a gradual puzzling out of that key.

Ultimately, what detective fiction did was to make this kind of puzzling out common sense, and only because the reader is placed into the shoes of a detective who works on behalf of a private government institution. A further development in detective fiction was the emergence of a new character popularized in the beginning of the twentieth century: the spy. Like the detective, the spy was a character who worked for the state, solving its mysteries, but with a widened (and often international) scope. The policing work of detection now happened outside of the state’s jurisdiction. This was especially prevalent after World War II and the establishment of the first British and American counter-intelligence agencies. It’s important to note that some of the people who founded the first such agencies in the United States, such as Alan Dulles, were part of an American aristocracy who held anti-semitic beliefs and even doctored records to make it appear that they had discontinued their financial relationships with Nazi Germany. As someone who loved spy stories growing up, learning this information was difficult for me to internalize. By identifying with characters like James Bond or their American variations, these stories encourage ‘ordinary’ readers to imagine themselves as lawless plutocrats able to steer world events and uncover terrorist plots by force of will.

The Purloined Letter

From Atilla Hallsby, (2018) "Psychoanalytic Methods and Critical Cultural Studies" in The Oxford Research Encylopedia of Communication.

The “Seminar on ‘The Purloined Letter’” is a 1955 lecture delivered by Jacques Lacan that is published in Écrits (2006). It is noteworthy because Edgar Allan Poe’s (1844) short story “The Purloined Letter,” is among the earliest examples of detective fiction. Lacan's seminar about the short story draws together an array of psychoanalytic concepts, including repetition, the agency of the signifier, and the registers of the unconscious. It is therefore a uniquely valuable anecdote for summarizing the role of the secret in psychoanalysis that features an early example of a protagonist whose detection is aligned with positions of figural authority (the monarchy and the police). Poe’s story is split into two scenes:

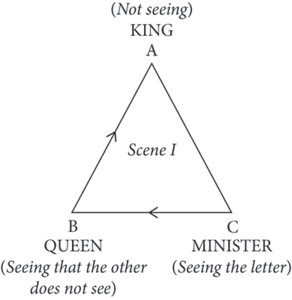

The first transpires in a ‘royal boudoir’ where the King and Queen are present. The Queen receives the compromising letter in the King’s presence, whereupon the Minister D- enters. The Minister quickly recognizes that the Queen is keeping a secret, and casually drops a decoy letter on the table. He then steals the dangerous document as the Queen watches, unable to stop him. The second scene features Poe’s analyst, Auguste Dupin. At this time, the Queen has commanded the Prefect of the Police to retrieve the letter. Although his officers employ state-of-the-art scientific techniques to find the letter, no amount of searching can uncover it. Exhausted by their failure, the Prefect consults Dupin for assistance. When Dupin enters the Minister’s home for a casual visit, he immediately sees the letter perched in plain sight, crumpled and “apparently thrust carelessly” between the legs of the Minister’s mantel. Artfully forgetting his snuffbox on the table, Dupin returns the following day, and substitutes the letter with a facsimile that bears his own signature. (Hallsby, 2015, p. 360)

Repetition (as belatedness/retroaction) is by far the star of the show. The recurrence of the second scene as a version of the first retroactively gives form and meaning to the events in the royal boudoir and organizes the narrative’s resolution. In the first scene (Figure 5), the King is blind to the letter, the Queen wishes for it to remain hidden, and Minister D- seizes the advantage of the intersubjective relationship he sees played out before him.

In the second scene (Figure 6), the police are blind to the letter, the Minister D- wishes for it to remain hidden, and Dupin — because he seizes upon the structure of Minister D-’s theft — takes advantage of D-’s blindspot. As Shoshana Felman (1987) explains, “[What] is repeated . . . is not a psychological act committed as a function of the individual psychology of a character, but three functional positions in a structure which, determining three different viewpoints, embody three different relations to the act of seeing – of seeing, specifically, the purloined letter” (p. 41).

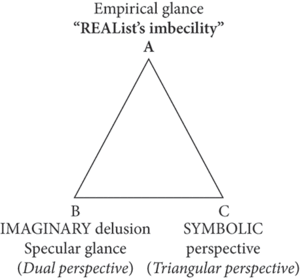

What are these “positions” or “relations” to the letter? (Figure 7)

- The first is the “realist imbecile,” the blind Other embodied first by the king and then by the prefect of the police.

- The second is the secret-keeper, who hides the letter, embodied first by the queen and then by the Minister D-. This position embodies the imaginary register and exists at the scale of the intersubjective dyad.

- The third is the secret-taker: it sees what the second sees and seizes the opportunity to remove the letter from its hiding place. The third position moves the letter from its place only to find himself occupying a different position in the intersubjective triangle. This relation is occupied first by the minister and then by Auguste Dupin. Each assumes the role of the symbolic insofar as they take a supra-position with respect to another intersubjective relation; by being in a position to “seize” the symbolic order, these characters identify themselves with it—only to find themselves “put into place” by the symbolic order.

The letter, of course, is the signifier that remains constant as characters and contexts shift around it.

When Lacan argues that the agency of the signifier is responsible for creating a network of intersubjective relationships, it is because the letter’s muted materiality organizes the range of intersubjective positions available to the characters in “The Purloined Letter.” At no point is the reader invited to read the letter’s compromising message, nor to consider why the Queen fears the King’s wrath. Instead, the recalcitrant signifier/letter has an agency of its own that draws characters into a network of dispossession and desire. The evidence of the signifier’s agency is that the logic of desire proceeds unhindered by the fact that the letter’s signified (i.e., its content or meaning) is completely obfuscated throughout the story. Moreover, the repetitious character of the triangular intersubjective relations of the story illustrates how the signifier (and not the legible secret that it contains) coordinates the distinct modes of desire that are oriented to it.

Additional Resources

Further Examples

- “Live PD exemplifies police transparency”/“Live PD destroyed evidence of brutality”

- Trailer for SWAT (2003)

- “No Coincidences at GFS”

- EJI Dedication of the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, AL

Detectives

- Joan Copjec, "Locked Room/Lonely Room" in Read My Desire: Lacan Against the Historicists

- Robert Terrill, "Put on a Happy Face: Batman as a Schizophrenic Savior"

Police

- Stuart Schrader, Badges Without Borders: How Global Counterinsurgency Transformed American Policing

- Patricia J. Williams, "Skittles as Matterphor"

- Joy James, Resisting State Violence

- Angela Davis, Are Prisons Obsolete?

- Angela Davis, Freedom is a Constant Struggle

- Alex Vitale, The End of Policing

- Alex McVey, "Point and Shoot: Police Media Labor and Technologies of Surveillance in End of Watch"

- Joshua Reeves and Jeremy Packer, "Police Media: The Governance of Territory, Speed, and Communication"

- Ines Valdez, Mat Coleman, and Amna Akbar, "Law, Police Violence, and Race: Grounding and Embodying the State of Exception"

- Shannon Winnubst, "The Many Lives of Fungibility: Anti-Blackness in Neoliberal Times"

- Ersula Ore, "Introduction" to Lynching: Violence, Rhetoric, and American Identity

- Guy DeBord, Comments XXVIII

- Louis Althusser, Selections from "Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses"

- Frantz Fanon, Selections from Black Skin/White Masks

To Cite This Page

- Atilla Hallsby (2022), "The Police and the Detective" in The UnTextbook of Rhetorical Theory: The Rhetoric of Secrecy and Surveillance. https://the-un-textbook.ghost.io/secrecy-and-surveillance-police/. Last Accessed (Day Month Year).