Who/what is the o/Other?

In psychoanalysis, the terms "other" and "Other" have a specific meaning. They refer to modes of identification, whereby the subject is granted some sense of their identity by referencing another person. Whereas the little-o other refers to a particular or specific other in the world, the big-O Other refers to a figural position of authority, someone who writes or guarantees the Law and enforces it as a measure of the rightness and wrongness of our actions. Sometimes, the big-O Other is called the "Superego" which can be both benevolent and cruel, leveraging an internalized voice of authority that both punishes and rewards.

Psychoanalytic Identification in Rhetoric

Early in the disciplinary history of American Rhetorical Studies (RS), the Freudian position was prestigiously associated with Kenneth Burke’s theory of identification. According to Diane Davis, Burke was enamored by Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams. In A Rhetoric of Motives, for instance, he glowingly cites “Freud’s notion of a dream that attains expression by stylistic subterfuges to evade the inhibitions of a moralistic censor.” Burke, however, also distanced himself from some of Freud’s more famous pronouncements. Namely, “he ditched the Oedipal narrative, arguing that the most fundamental human desire is social rather than sexual.” Whatever their differences, for Burke as for Freud, identification happens to a subject who first encounters their identity by way of being dispossessed: “Boy wants Momma, Daddy has Momma, so boy wants to be Daddy, identifies with him, takes him as the ideal model.” Identity is motivated not by the desire to have what the other has (in this case, the maternal love-object), but by the desire to become the other who has (or once had) what the subject cannot stop wanting. The fact that the other ‘has’ the (maternal love) object throws the desiring subject’s own dispossession (lack-of-the-object) into relief. Put somewhat differently, identification is not an obsession held in common with another subject, but rather how the assumed commonness of obsession enables the subject to put themselves in the other’s place. The difference between the identifying subject (A) and the subject with whom A identifies (B) is prominently featured in Burke’s own construction:

A [the subject] is not identical with his colleague, B. But insofar as their interests are joined, A is identified with B. Or he may identify himself with B even when their interests are not joined, if he assumes that they are, or is persuaded to believe so.

Identification is an imperfect and often imagined match between the interests of A and B. When A imagines their interests and desires as identical to B’s, they become identified. Even when the distinction between A’s desire and B’s desire is strictly policed (as, for instance, is the case in the distinction between boy’s/father’s desire for the mother), identification consists in the (mis-)recognition of this innate difference as sameness, and the other’s desire as “consubstantial” with one’s own:

While consubstantial with its parents, with the “firsts” from which it is derived, the offspring is nonetheless apart from them. In this sense, there is nothing abstruse in the statement that the offspring both is and is not one with its parentage. Similarly, two persons may be identified in terms of some principle they share in common, an “identification” that does not deny their distinctness.

Identification has a final crucial component: the introduction of a mediating third party. When A identifies with B by imagining themselves in B’s place, it is a third party – the (maternal) object or “some principle they share in common” – that authorizes A to become B while also relegating B to the status of an antagonist or competitor. The Freudian/Burkean inflection on identification stresses that there is no identity prior to the subject’s persisting attachment to that which they hold in common. For identification to occur, A must therefore make and break their relationship to B vis-à-vis the object they both hold dear.

Imaginary and Symbolic Identification

Unlike Freud’s repressed unconscious that must be discovered or unveiled, Lacan’s unconscious speaks through the subject with the associative logic of “impediment[s], failure[s], [and] split[s].” Lacan famously explains identification as a split in the subject occurring during the mirror stage, the moment a child first recognizes itself in its reflection. Before the mirror stage, the subject “… putatively lacks any sense of itself as an individual, crying when other infants cry and understanding its body and motions as unconnected fragments.” But when the infant confronts and recognizes itself in the mirror (“the exotic fixity of the child’s reflected image”) a split appears in the subject’s self-perception: “The image simulates the idea of an entity entirely independent of herself in a ‘looking glass’ or reflective surface.” This passage from putative wholeness to differentiated identity is identification: the process by which the subject recognizes itself by reference to a split in itself. Ultimately, the recognition of the image in the mirror (or "imago") is experienced as a loss for the subject, who thenceforth will ceaselessly attempt to “resolve, as I, his discordance with his own reality.”

Lacan’s elsewhere explains the identification as a different sort of splitting, this time between the subject’s attachments in the imaginary and symbolic registers. The splitting of identification is like the splitting of the signifier from the signified because it marks how Lacan’s unconscious privileges “impediment, failure, split” as the core feature of the subject.

- In imaginary identification, the subject “imitate[s] the other at the level of resemblance, we identify ourselves with the image of the other inasmuch as we are ‘like him’.” At this level, the subject relates to the other as an ego ideal (or little-o other): the subject that the subject would (or would not) like to become. Little-o others are those others who are more-or-less like us; they occupy the position of the want-to-be in the sense that we want to look, act, and achieve in the same way or, alternatively, look to this other as a negative example of how not-to-be.

In the case [of Charles ‘Lucky’ Luciano], the nickname tends to replace the first name (we usually speak simply of ‘Lucky Luciano’) … . … The nickname alludes to some extraordinary event which has marked the individual (Charles Luciano was ‘lucky’ to have survived the savage torture of his gangster enemies) – it alludes, that is, to a positive, descriptive feature which fascinates us; it marks something that sticks out on the individual, something that offers itself to our gaze, something seen, not the point from which we observe the individual. ... In imaginary identification we imitate the other at the level of resemblance – we identify ourselves with the image of the other inasmuch as we are ‘like him’. (Zizek, The Sublime Object of Ideology, 120-1)

- Symbolic identification is the position from which the subject judges their own actions and is likable to themselves. It is the internal voice of authority insofar as we measure the 'goodness' of our actions according to an internalized perspective in terms associated with the parent, the priest, the psychoanalyst, the teacher, or the president (and the list can go on). At the level of symbolic identification, by contrast, “we identify ourselves with the (big-O) Other precisely at a point at which he is inimitable, at the point that eludes resemblance.” This mode of identification situates the Ideal ego (or big-O Other) as the position of illusory authority from which the subject imagines their actions to be judged. These figural roles of authority describe "the [big-O] Other". This mode of identification allows the subject to assume a role in relation to the illusory completeness of an Other who decides or judges in the subject’s place.

"Incest Prohibition" as Allegory of the Big-O Other

Often, the figural voice of the big-O Other returns to us in the form of specific representations of authority like the police, the settler, the dictator, and the boss. Often, this authority is repressive, telling us what not to do as much as it authorizes us to act. As an illustration of this kind of voice of authority and the names it receives, consider the exchange below between historian and public intellectual Gore Vidal and conservative founder of the National Review William F. Buckley:

One of Freud's examples of the Superego as a repressive voice of authority comes in the form of the "Father" in the incest prohibition myth. Although the myth is problematic for the way that it makes a hypothetical primitive society a model for 'advanced' human behavior (and thus reinforces a distinction between "uncivilized" and "civilized" psychologies) it illustrates how “[the] tendency of culture to set restrictions upon sexual life” generates the repressive social function of the law. This is Freud’s myth of the primal father, who after exiling his sons and subordinates claims all the women for his own. This primal father figure, the subject of gratuitous pleasure, is subsequently murdered and a law prohibiting incest is instituted among the remaining tribe. Freud thus installs a repressed sexual motive as a founding social bond:

Though the brothers had banded together in order to overcome their father, they were all one another’s rivals in regard to women. Each of them would have wished, like his father, to have all the women to himself. The new organization would have collapsed in a struggle of all against all, for none of them was of such overmastering strength as to be able to take on his father’s part with success. Thus the brothers had no alternative, if they were to live together, but – not perhaps, until they had passed through many dangerous crises – to institute the law against incest, by which they all alike renounced the women whom they desired and who had been their chief motive for dispatching their father. In this way they rescued the organization which had made them strong – and which may have been based on homosexual feelings and acts, originating perhaps during the period of their expulsion from the horde.

The point of this admittedly strange story is that the murder of the father occurs because the law is too repressive, too reprehensible, too brutal – the father represents a kind of unrestricted pleasure without regard for the consequences or the pain it brings to others. The Law which is set up after the father's murder takes the place of this big-O Other as his symbolic substitute. Instead of an unrestricted, unrepressed Id, the Law assumes the form of a censorious Superego that says "thou shalt not" as a way to ensure that the kind of activity represented by the primal father – the original mythic figure of authority – never comes to pass again.

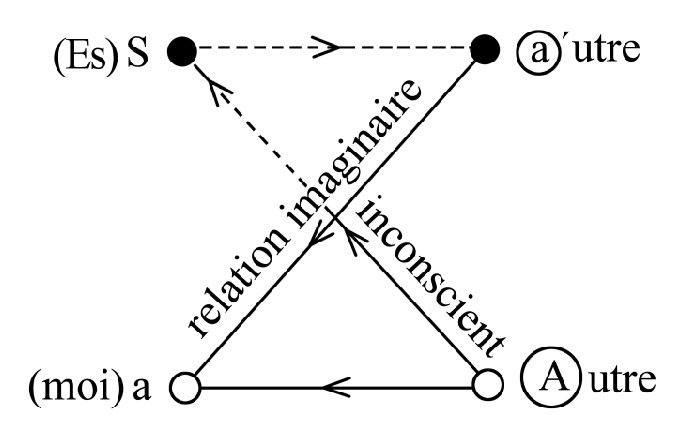

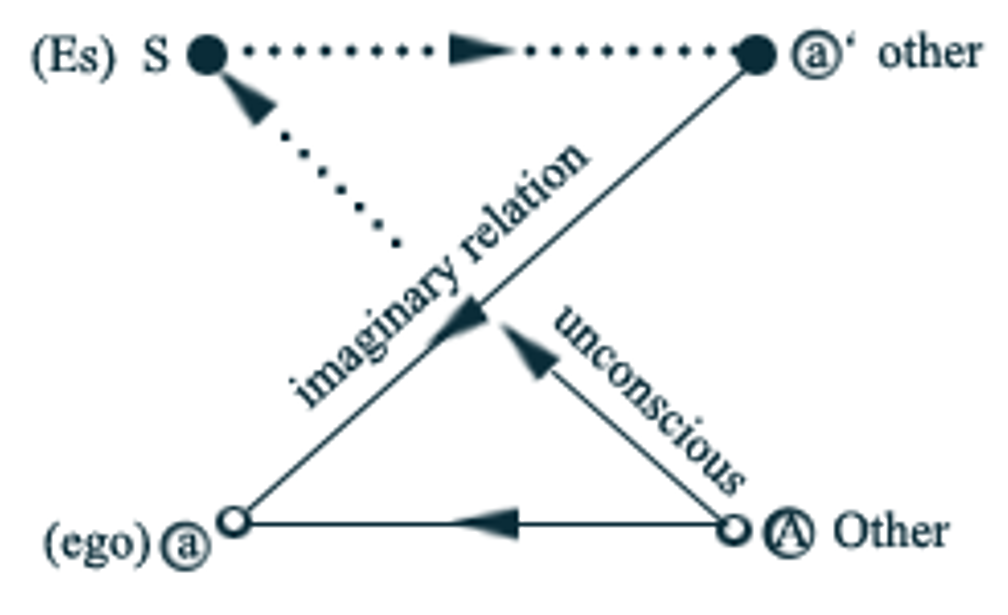

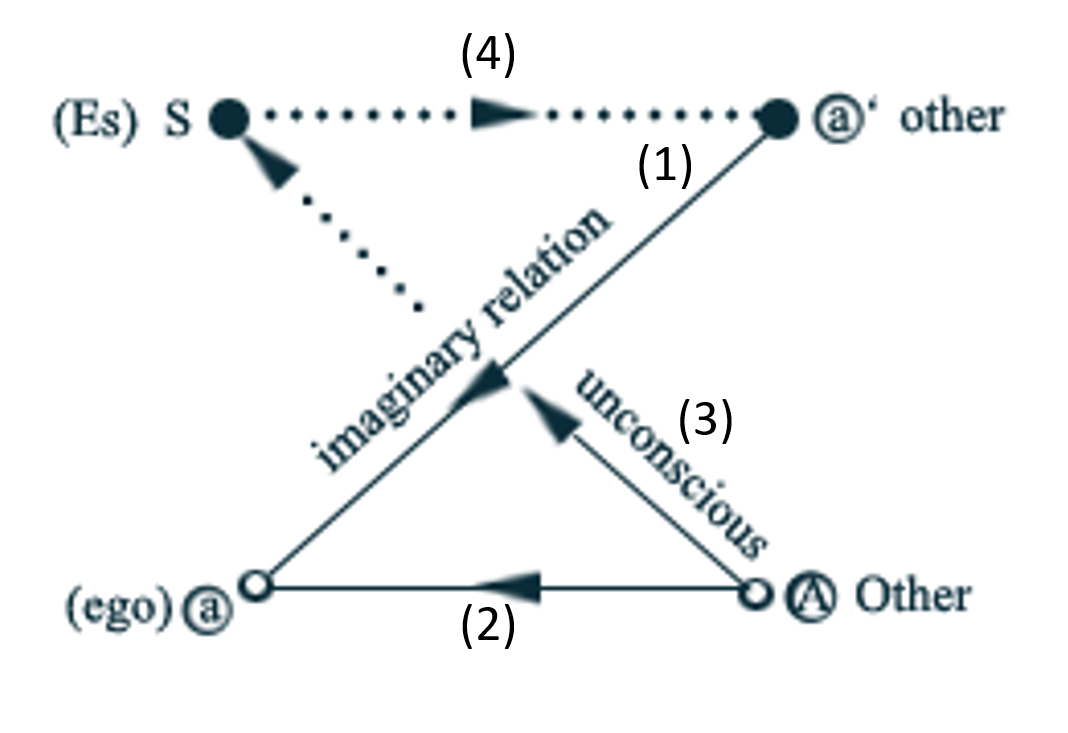

Schema L: There are always (at least) four parties to any interaction.

What about the diagram at the top of this page? What does that mean? How are the little-o other and the big-O Other involved? Admittedly, this is a complicated question with a complicated answer, which is not particularly obvious just by looking at the diagram.

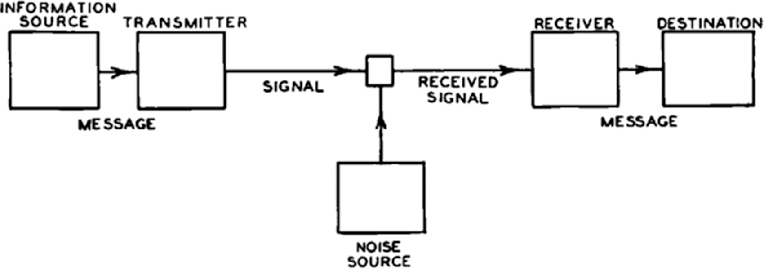

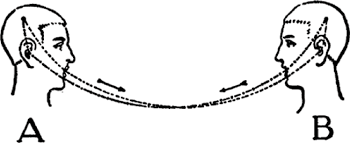

The first thing to note is that the diagram is intended as a modification and complication of the traditional sender/receiver model of communication. It may help to think of the total diagram less as two separate people engaged in a conversation and more as one person's projection of a relationship upon others, which is used as a template for interacting with any other person. In other words, it describes the baggage that a single subject brings to a given interaction and not the separate intentions that two different people bring to a dyadic conversation.

"[T]he ego isn’t even conceivable without the system, if one can put it this way, of the other. The ego has a reference to the other . . . [and] is constituted in relation to the other." ... [It] is an elaborate way of saying that subjects address others as objects to confirm their pre-existent understandings of the world. (Christian Lundberg, quoting Jacques Lacan. From Lundberg's Lacan in Public, 63)

There are at least two significant differences from the traditional model:

1. The Split Sender/Receiver

First, neither the sender nor the receiver is a unified and singular subject. Instead, each is split. Like the sender/receiver model of communication, the schema L is split along the vertical axis between the subject (on the left, represented by ‘Es’ and ‘ego’) and the other/Other (on the right).

- The "sender" is split between the "Es" ('it' or 'id'), the pre-mirror stage subject, and the "ego," the post-mirror stage subject who possesses consciousness and differentiates themselves from other subjects and objects in the world. The Es (upper left) is “the disorganized material, biological and experiential reality of having a body,” whereas the post-mirror-stage ego (lower left) is the “… image of identity that retroactively imposes both unity and meaning” onto the subject. You might imagine the "Es" as the babbling baby without language depicted in the video above, whose relationship to others is dictated by imitation and repetition, and which is a part of oneself that is difficult to consciously perceive. It is the part of the self that desires recognition and approval. The "ego" is the conscious self, the subject with language, who can perceive differences between mere babble and true speech.

- The "receiver" is split between the little-o other and the big-O Other, or the other of imaginary identification and the Other of symbolic identification. The imaginary little-o other (upper-right) is “the manifest addressee of speech,” and the symbolic big-O Other (lower right) is the superego, the voice of the Law and figural authority, which legitimates and judges the subject's thoughts and actions. The position of the little-o other and big-O Other is projected upon the interlocutor in an exchange. We consciously register our conversation partners through an imaginary register and project upon them the role of the big-O Other, which makes our actions either valid or immoral. As Christian Lundberg argues, the purpose of distinguishing little-o other and big-O Other is to highlight the greater importance of the big-O Other relative to the small-o others with whom the subject is usually engaged.

2. Reversing the Flow of Communication

Second, the message does not move from sender to receiver but from receiver to sender – that is, from the subject's unconscious to their conscious self. Even before we come to or begin speaking in communicative interactions, the other/Other is sending us a message, not the other way around. The mesh of dotted and solid lines illustrates the relationship between the subject’s ego and the particular others with whom they engage.

- (1) The little o-other (a) speaks to the ego. This is where the resemblance to the original sender/receiver model begins and ends. This relationship is represented by the solid line that moves from the little-o other (a) on the upper right quadrant to the lower left quadrant. This is also labeled as "the imaginary relation" in which the little-o other assumes the role of the 'want to be,' in which we consciously apprehend others as more or less like ourselves based on the noticeable signifiers the little-o other (a) presents to us. People in the world speak to us with their signifiers, and we as conscious subjects interpret what they say based on the representational frameworks with which we are most familiar.

- (2) The big-O Other (A) 'speaks' to the ego. This is the relation by which the big-O Other tells the subject how it may be likable to itself. We as conscious subjects (ego) can receive a message from the big-O Other, but can't send one back. We seek approval or authorization from a figural authority figure, but they do not seek ours. If a teacher tells you that you have great writing skills or a therapist tells you that you are engaged in a destructive pattern of behavior, that message comes through language from this figural authority figure, but the relationship of approval or judgment seems to go only in the one direction.

- (3) The big-O Other (A) 'speaks' to the subject (Es). This message is always distorted by the imaginary relation (1) and is therefore routed back to the conscious ego. The trouble is that the big-O Other never seems to speak to the subject's pre-linguistic, pre-symbolic self (Es) directly. Instead, this communication is always mediated by an imaginary relationship; we only get access to 'the' big-O Other through a particular little-o other. Earlier in this entry, I explained that the big-O Other is thought of in many ways: for example, as "the Law," "God," "the police," "the therapist," or "the father." These are all imaginary constructions of the big-O Other. However, there is no direct access to the big-O Other 'as such' in an unmediated or direct form. It may appear to the conscious ego that the big-O Other is speaking to us directly if, for instance, we are taken to task by a specific authority figure in our lives. However, this authority figure is only ever a substitute for the figural position of authority we internalize as the big-O Other. As Christian Lundberg explains, the broken lines on the diagram represent a relationship of immediacy, in the sense that these messages are not 'actually' coming from the figural authority figure, but are applied or projected by the Subject onto others.

The analyst [or therapist] who believes she is adopting the most dispassionate tone of voice in speaking to the analysand [or patient] is taxed with being hypercritical, like the [patient's] father ... [and this] persists despite every attempt to eliminate it. The [therapist's] remarks are still heard by the [patient] as coming from the person he imputes her to be, even if that is not who she feels herself to be, even if that is not where she is trying to situate herself. The person he imputes her to be is ... the [big-O] Other (the representative of his parents' or culture's ideals and values, an authority figure, or a judge, for example). Even when the [therapist] deliberately strives to assume [a neutral] role ... what she says is heard by the [patient] as coming from some [big-O] Other place and, moreover, as addressing something in him that is beyond his observing ego [the Es], something in him that is beyond the "cooperative" ego he tries to play the role of in the therapy relationship (Bruce Fink Lacan to the Letter, 7)

- (4) Finally, the subject (Es) 'speaks' to the little-0 0ther. This is how we as subjects, who retain the trace of our pre-linguistic selves, project our desires upon the others that we see, meet, and interact with. This desire isn't something that we say so much as something we assume, often without so much as realizing it. This relationship is one of expectation and wish-fulfillment, in the sense that we may wish for the other to like us, we may wish to be like the other, or in the sense that perceived similarity between the subject and other alerts us to something dislikable in ourselves. Similar to the pre-linguistic subject (i.e., the babbling baby) our relationship is here dictated automatically, unconsciously, on the basis of our likeness to the other even in the face of our difference from them.

Lacan explains the total movement of the schema-L with the phrase ‘the letter always arrives at its destination.’ In other words, the big-O Other in control of how we receive messages in any interpersonal interaction, and this internalized Other enables the unconscious subject to send a message to themselves through their interactions with others, who are effectively the medium for their own unconscious.

Additional Resources

- Franz Kafka, "Before the Law"