Speech Acts, Signs, and the Personae

Speech Acts

- Austin, How to Do Things with Words

- Butler, “Burning Acts, Injurious Speech,” and “On Linguistic Vulnerability”

- Gunn, “On Speech and Public Release”

The Sign

- Saussure, Course in General Linguistics

- Barthes, Mythologies (Atilla's notes on Saussure and Barthes from ~2009)

- Culler, The Pursuit of Signs: Semiotics, Literature, Deconstruction

- Gates Jr., The Signifying Monkey: A Theory of African-American Literary Criticism

- Silverman, “Liberty, Maternity, Commodification”

- Norton, “The President as Sign” in Republic of Signs

Persona

- Black, “The Second Persona,”

- Cloud, “The Null Persona: Race and the Rhetoric of Silence in the Uprising of ‘34”

- Wander, “The Third Persona: An Ideological Turn in Rhetorical Theory”

- Morris IV, “Pink Herring & the Fourth Persona”

- Ede and Lunsford, “Audience Addressed/Audience Invoked”

Background on Speech Acts, Signs, & Persona

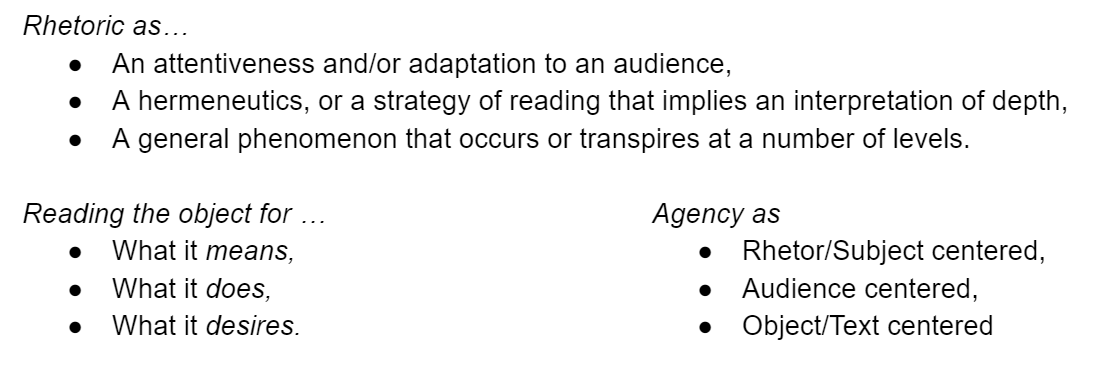

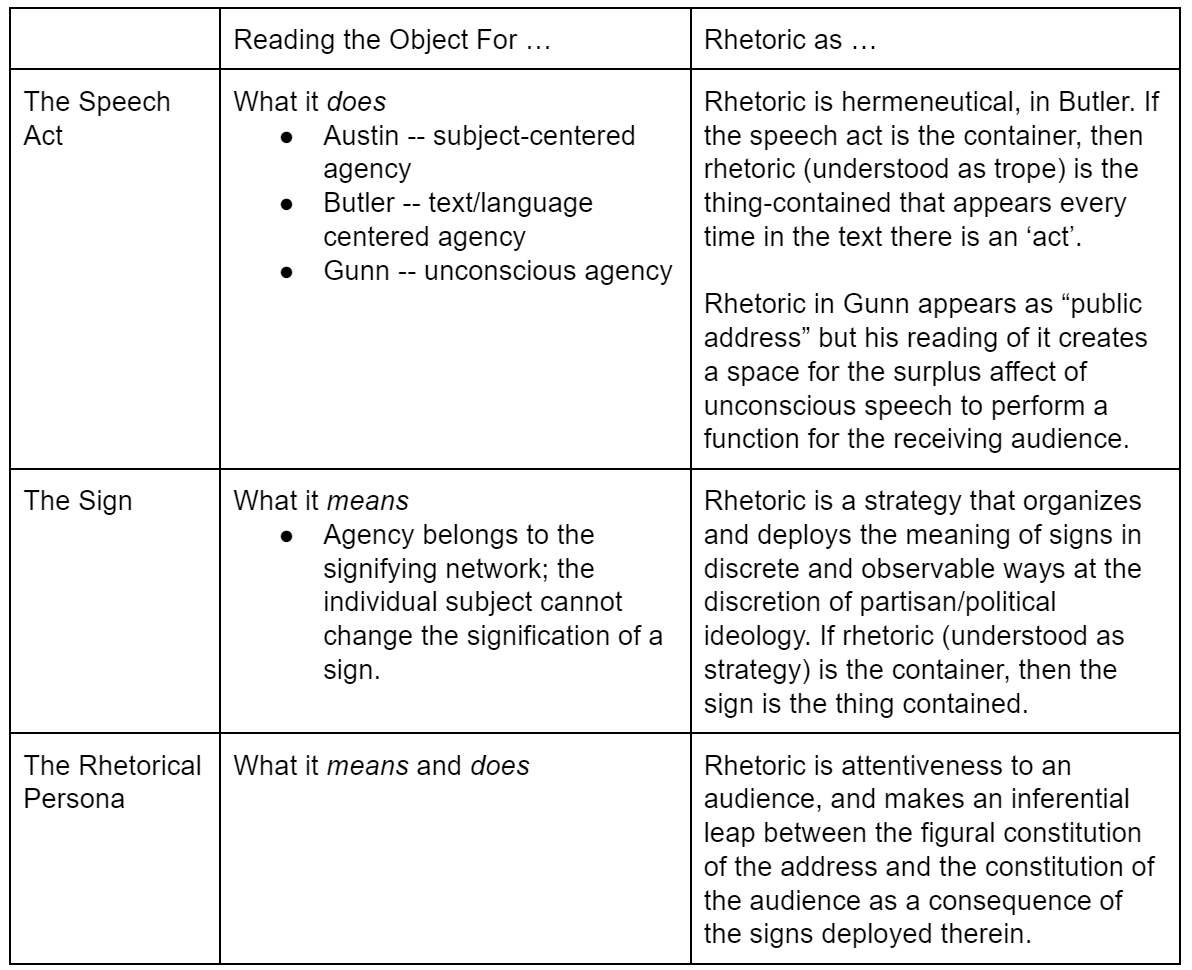

The purpose of presenting these three topics together is to consider what makes each of these objects of rhetorical criticism unique. In previous sessions, we discussed the following:

My purpose for focusing in on the speech act, sign theory, and rhetorical personas is twofold:

- first, to illustrate how these are related theories, and that a rhetorical critic could ostensibly read the *same* text at each of these levels, yielding a different kind of interpretation in each case. From that point of view, we might consider thinking about a central, focal ‘text’ and how each of the theories described today -- speech act, sign, and persona -- could be systematically applied to it.

- Second, to indicate that these are different frameworks or perspectives that underwrite many rhetoricians’ assumptions when they perform the criticism of a speech or otherwise rhetorical text.

Below, you will find a short review of speech act, sign, and persona.

Speech Acts

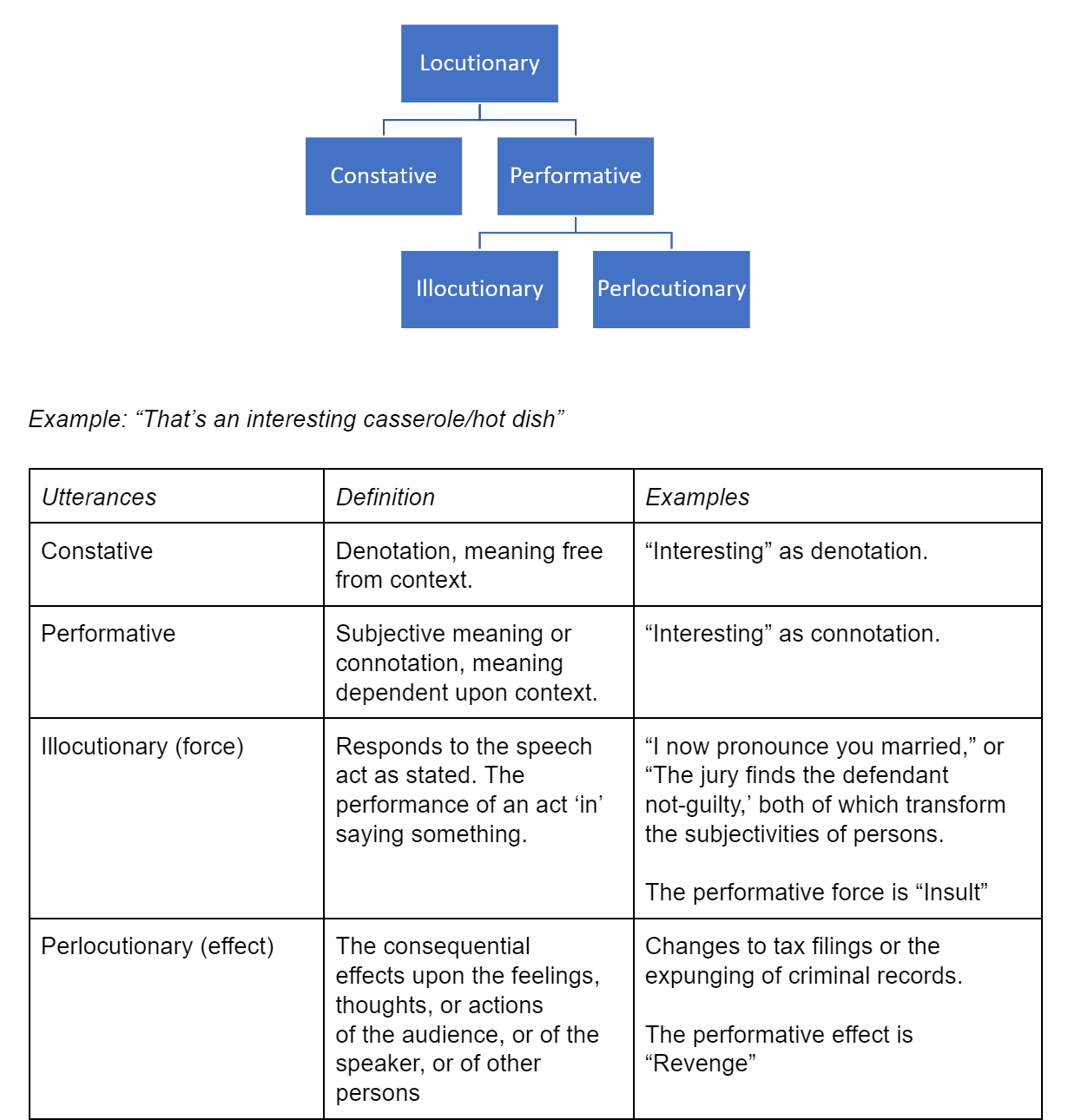

The theory of speech acts is typically attributed to J.L. Austin, a British ordinary language philosopher. His schema of the locution (shown below) offered important and widely cited distinctions between the constatives and performatives, and within the category of performatives, illocutionary force and perlocutionary effects. Austin’s work is featured in the work of John Searle (another linguist/pragmatist), Jacques Derrida (the originator of ‘deconstruction’) and Judith Butler (theorist of gender whose work is deeply informed by deconstruction). When we talk about speech acts today, it's typically in reference to their use in the way Derrida and Butler theorize them.

If Austin sets up a set of exclusive categories and divisions, deconstruction as a reading strategy addresses itself to the way that categories that are supposed to be mutually exclusive are in fact mutually dependent. Derrida addresses the layer of the “constative” (or not context dependent for meaning) and “performative” (depending on context for meaning) to illustrate how there is no utterance that is not itself dependent on a context, or a performative utterance. Butler attaches the performative to a series of important political questions related to injurious speech as a “violating interpellation”:

If performativity requires a power to effect or enact what one names, then who will be the "one" with such a power, and how will such a power be thought? How might we account for the injurious word within such a framework, the word that not only names a social subject, but constructs that subject in the naming, and constructs that subject through a violating interpellation? Is it the power of a "one" to effect such an injury through the wielding of the injurious name, or is that a power accrued through time which is concealed at the moment that a single subject utters its injurious terms? Does the "one" who speaks the term cite the term, thereby establishing him or herself as the author while at the same time establishing the derivative status of that authorship? Is a community and history of such speakers not magically invoked at the moment in which that utterance is spoken? And if and when that utterance brings injury, is it the utterance or the utterer who is the cause of the injury, or does that utterance perform its injury through a transitivity that cannot be reduced to a causal or intentional process originating in a singular subject? (Excitable Speech, p. 49)

Tropes and Performative Speech Acts

Butler addresses the distinction between illocutionary force and perlocutionary utterance and attaches trope to the illocutionary force of the utterance. The rhetorical structure of a text or performance is what it does ‘in the saying,’ whether we are talking about a drag show (irony in Gender Trouble) or a legal document (metaphor, metonymy, and synecdoche in Excitable Speech). As Butler writes,

If a word in this sense might be said to "do" a thing, then it appears that the word not only signifies a thing, but that this signification will also be an enactment of the thing. It seems here that the meaning of a performative act is to be found in this apparent coincidence of signifying and enacting. And yet it seems that this "act-like" quality of the performative is itself an achievement of a different order, and that de Man was clearly on to something when he asked whether a trope is not animated at the moment when we claim that language "acts;' that language posits itself in a series of distinct acts, and that its primary function might be understood as this kind of periodic acting. (Excitable Speech pp. 44-45)

Signs

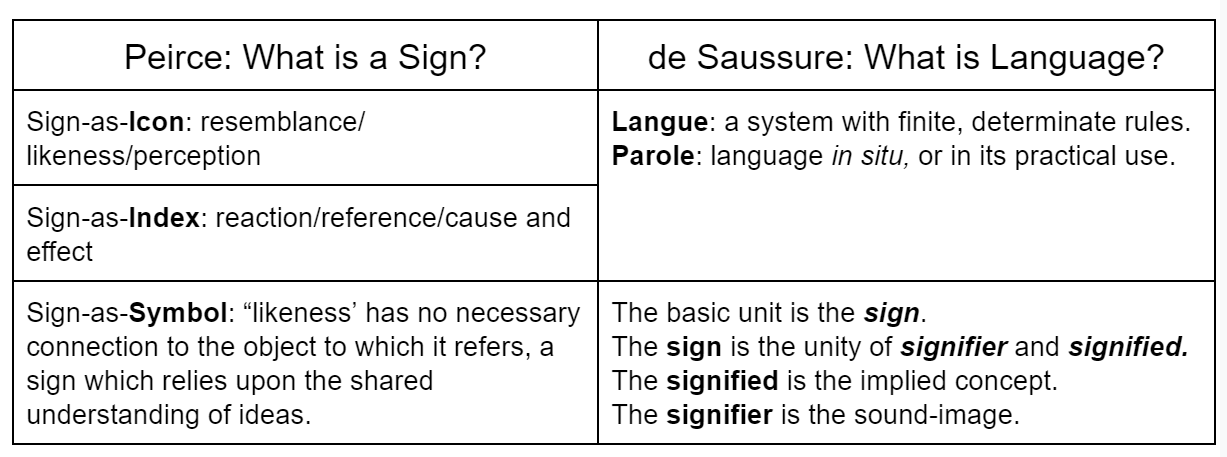

The theory of the sign is often attributed to one of two 20th-century philosophers: Ferdinand de Saussure and Charles Sanders Peirce (pronounced ‘purse’). Peirce developed, among other theories, a three-part theory of the icon (a sensory resemblance), the index (a referential relationship) and the symbol (a meaning governed by convention). Saussure is known for his modernist theory of the language, in which the sign gives a structure and form to meaning and its transformation over time.

Signs and Ideology

Saussure’s theory of language is revised by Roland Barthes who proposes that ideology works through the process of second order signification which he also terms myth. When ideology operates through the logic of the sign, it means that the concepts implied by our language contribute signifiers to a larger reservoir of shared meaning-making that defines our relationships to governing (imperialist or capitalist) structures.

It should also be noted that Barthes’s demonstration of second-order signification is a magazine cover whose mythic signification is French colonialism in Algeria. The Lacanian extension of this reasoning by Slavoj Zizek in The Sublime Object of Ideology describes the disavowal of the commodity-form as a fundamental operation of ideology. Disavowal takes the form of a logical excusal or self-justification: “I know very well that …, but nonetheless ….” For example, I know very well that capitalism is causing climate change and that my consumption habits partake in the problem, but nonetheless I continue purchasing products and goods, to the point of purchasing “eco-friendly” and “greenwashed” products to compensate for my complicity in that system. To the extent that we use language to keep what we know at bay, ideology is both unconscious and exists at the level of the signs we use.

The Differential Play of Signs

One important aspect of the sign is that it gains its force and value through its differential relationship to other signs. A sign is a sign by virtue that it is not other signs, that it means something in its difference from other signs that inhabit the sign system. This is, for instance, how Michael McGee (who borrows from Roland Barthes without citing him) conceptualizes the ideograph, which at a given (synchronic) moment of time, draws its meaning from other ideologically-charged signs. Similarly, the statue of liberty achieves its sign value through the play of signs, such as the artwork of Bartholdi, Delacroix, and Daumier.

Rhetorical Persona

A persona is a figure constructed by the speaker, and most often refers to the implied audience or the audience as it is constructed by the speaker. It can refer to the speaker themselves (1st persona), the ideologically conditioned audience (2nd persona), an implied-but-excluded audience (3rd persona), the subversive “collusive” audience that is ‘in’ on the speaker’s double entendres (4th persona), the self-negation of the speaker and the creation of the text of an oblique silhouette indicating what is not utterable (null persona) or a strategy used by those who have achieved or experienced something beyond traditional expectations (transcendent persona). Rhetorical personas take features of text and context and use them to draw conclusions about who that audience was and was meant to imagine themselves -- and the speaker -- to be. Many times, the rationale for attending to a text’s persona is its present-day perlocutionary effects, which are presumed to be tied to the illocutionary force of the speech supposed to have constituted its audience.

Part 1: Speech

Presentation by Brandi Fuglsby

- J.L. Austin, “Lecture I: Performatives and Constatives,” and “Lectures V-IX,” in How to do Things with Words, 1-11; 53-120.

- Judith Butler, “Burning Acts, Injurious Speech” in Excitable Speech: A Politics of the Performative 43-70.

- Supplemental Reading: Judith Butler, “On Linguistic Vulnerability” in Excitable Speech: A Politics of the Performative 1-42.

- Joshua Gunn, “On Speech and Public Release “in Rhetoric and Public Affairs 13 (2010), 1-42.

By taking “speech” as an object this week, we are moving away from the exclusive understanding of speech as political oratory, and instead broadening it to a form of everyday communication practice. A foundational thinker for this mode of thinking in rhetorical studies was JL Austin, who was both an ordinary language philosopher and a member of the Pragmatic disciplinary orientation to Linguistics. There are hints of Austin’s pragmatic approach in Bitzer’s The Rhetorical Situation, although speech act theory has been taken up by critical theorists to describe the discursive making of identity (such as Butler). Austin makes a number of distinctions in How to do Things with Words. For example, constative utterances (utterances which may be ‘true’ or ‘false’) are distinguished from performative utterances (utterances that are not truth-evaluable but either ‘felicitious’/successful or ‘inflecitious’/unsuccessful). Within the category of performative utterances, Austin’s distinguishes between the three parts of the speech act:

- Locution: the level of description, the semantic or literal significance of the utterance.

- Illocution (or illocutionary force): the intention of the speaker, the point of an utterance, and the particular presuppositions and attitudes that must accompany that point. Illocutionary force distinguishes the following types of acts (for example):

- Asserting, Promising, Excommunicating, Exclaiming in pain, Inquiring, Ordering

- Perlocution (or perlocutionary effect): how the utterance was received by the listener or viewed at the level of its consequences. The perlocutionary effect

- Persuading, Convincing, Scaring, Enlightening, Inspiring

Judith Butler’s concern with the performative utterance merges Austin’s formula with Louis Althusser’s theory of interpellation, which explains how “being called a name is also one of the conditions by which a subject is constituted in language.” (2) Butler also follows Jacques Derrida’s critique of Austin in Signature Event Context, arguing that a logical contradiction in the definition of the illocutionary speech act prevents Austin from being able to sufficiently theorize the kinds of claims we make “when we claim to have been injured by language.” (Butler, 1) The distinction between illocutionary and perlocutionary speech act is explained in the following way:

- [Illocutionary speech acts are] speech acts that, in saying do what they say, and do it in the moment of that saying;

- [Perlocutionary speech acts] are speech acts that produce certain effects as their consequence; by saying something, a certain effect follows.

- The illocutionary speech act is itself the deed that it effects; the perlocutionary merely leads to certain effects that are not the same as the speech act itself. (Butler, 3)

However, Austin also claims that illocutionary speech acts must be “ritual or ceremonial,” even though their defining quality is that they are done ‘in the moment,’ or ‘in the saying’. In Butler’s words, “The illocutionary speech act performs its deed at the moment of the utterance, and yet to the extent that it is ritualized, it is never merely a single moment.” If the illocution, the deed (injury) done in the saying happens as “an effect of prior and future invocations that constitute and escape the instance of utterance,” then it is not because there is a single specific context that defines the illocutionary utterance (e.g. the “I do” of marriage) but rather a lack of singular (i.e. plural) context that gives injurious speech its force. (3) Butler’s use of speech act theory underwrites the idea of injurious speech that gets its force because it is an act that both has and could beset the subject anytime and anywhere.

To be injured by speech is to suffer a loss of context, that is, not to know where you are. Indeed, it may be that what is unanticipated about the injurious speech act is what constitutes its injury, the sense of putting its addressee out of control. The capacity to circumscribe the situation of the speech act is jeopardized at the moment of injurious address. To be addressed injuriously is not only to be open to an unknown future, but not to know the time and place of injury, and to suffer the disorientation of one’s situation as the effect of speech. (Butler, 4)

Introduction

So far this semester, we’ve read pieces centered around rhetoric as meaning. This week’s readings, however, represent a switch in that stance to rhetoric as doing. The first few readings for this week focus on everyday speech (as opposed to text) as an object and offer examples of this switch from speech meaning something to doing something. In other words, speech isn’t simply an utterance of one person’s interpretation of a topic, nor a collection of symbols presented by the speaker; instead, multiple factors, including those from the past and future, contribute to the message to elicit action. The meaning-making of a speech extends beyond the speech itself by drawing on past events/connotations and an acknowledgement that the message will change/be interpreted differently in the future. What follows is a more in-depth summary of each essay’s main argument, an explanation of how these essays connect, and an assertion of how these pieces center rhetoric.

J. L. Austin’s How to Do Things with Words

In his lecture collection, Austin claims that the established types of sentences (declarative, interrogative, exclamatory, and imperative) leave out a set of sentences he calls “performative utterances.” Throughout the lectures, then, he attempts to define, explain, and taxonomize these utterances, which he describes as “the performing of an action” (6). He contends that performative utterances are neither truths nor lies; they merely state an act that a person is claiming to do. He offers examples of these performative utterances throughout his lectures, including these:

- “I name this ship the Queen Elizabeth” (5).

- “I congratulate you” (40).

- “I argue (or urge) that there is no backside to the moon” (85).

These examples demonstrate how the speaker intends to or claims to perform an action, despite not necessarily following through. As such, they are performative utterances, as opposed to the other types of sentences.

After establishing the definition of a performative utterance, Austin then explained that performative utterances end in either a “happy” or an “unhappy” way, depending on six conditions (listed on pages 14 & 15). Austin explains that if even one of those conditions fails to come to fruition, then the outcome is an infelicitous one.

Perhaps the most important takeaway from Austin’s work is his division of the performative utterance into two parts: the illocutionary and the perlocutionary acts. Both acts refer to the responses of the audience—after the speech act has taken place. The illocutionary act refers to an act that responds to the speech act as stated; the perlocutionary act refers to an act that responds to the speech act contrary to what was stated (Austin 99-101). As a speech act taxonomy, the central terms mentioned throughout his lectures relate to one another in this way:

Judith Butler’s “Burning Acts, Injurious Speech” and “On Linguistic Vulnerability”

In the next readings, Judith Butler argued that the speech act, including an injurious one, can produce a physical response, such as temporary paralysis (2) or disorientation (4). She began by describing the effects of name-calling, both in a positive sense, as a pleasant hearing of our own name that has marked us for “social existence” (2), and in the negative, as being “injured” from a demeaning remark (2). She then argues that, “by being interpellated within the terms of language […] a certain social existence of the body first becomes possible” (5). However, because of the relationship of the body to language, language can harm the body. To demonstrate her point, Butler cites Tony Morrison’s parable of some children cruelly asking a blind woman whether the bird that they hold is alive or dead. The woman refuses to answer the question, one which she couldn’t have answered with certainty, and instead states what she does know: that, literally, the bird is in their hands and that, metaphorically, whatever state the bird is in is due to the children’s cruelty. Butler uses Morrison’s parable (as Morrison herself used it) to demonstrate that “‘oppressive language . . . is violence,’ not merely a representation of it” (9). In this case, the children attempted to humiliate the blind woman and thus transfer their violence from the (dead) bird to the woman.

Another main point in Butler’s essay is that, although injurious language “carries trauma” (38), ignoring that language altogether is not the answer. Instead, that language needs to be confronted and spoken so that “appropriating, reversing, and recontextualizing such utterances become possible” (39). Earlier in the piece, she had offered the example of “queer” as having been rightfully “‘returned’ to its speaker” (14).

In the second piece, Butler applies her injurious language theory to a case study, specifically, R. A. V. v. St. Paul, where “[a] white teenager was charged under this ordinance [Section 292.02] after burning a cross in front of a black family’s house” (52). Throughout this chapter, Butler shows how the courts ignored the injuriousness—in this case, the context—under the guise of the First Amendment. The ordinance, by explicitly outlawing cross burning, came across as contradicting the First Amendment’s essence. Siding with the city would have meant “the incineration of free speech” (55) and would have conveyed a perceived threat on those who defend the Constitution for a living, those in power. Another example was the court’s use of the phrase “someone’s front yard,” thereby effecting “[t]he stripping of blackness and family from the figure of the complainant” (55). Erasing the family’s blackness “refuses […] the racist history of the convention of cross-burning by the Ku Klux Klan” (55). Through these examples, Butler demonstrates how injuriousness recirculated by the court ignoring the context: “The reality of ongoing racism and exclusion is erased and bigotry is redefined as majoritarian condemnation of racist views” (60). The past, present, and future all clearly play an important role in this situation, yet the court ignored the context and thereby perpetuated racism, rather than confronting it.

Joshua Gunn’s “On Speech and Public Release”

In this last reading, Joshua Gunn argues that speech is an intimate act between the speaker and audience, and the most eloquent speaker is the one who can keep “uncontrolled speech” unspoken. “Uncontrolled speech” refers to the risks involved when one partakes in the object of speech and includes (but is not limited to) cries, stammers, screams, hiccups, grunts, and belches. He offers numerous examples throughout his essay, including tennis athletes’ once controversial grunting, Howard Dean’s career-ending “I Have a Scream Speech,” and Sally’s unforgettable fake orgasm in When Harry Met Sally. These examples demonstrate uncontrolled speech being “of the body; it reminds the hearer of a body, the body” (11), a physical and sexual entity that “measured speech always threatens to reveal” (5). It “gives one a glimpse of the unscripted, unconscious self” (15), for “speech can betray what we wish to conceal” (15). Here, he places Hilary Clinton in her “Shame on You” speech. At the other extreme, as identified by Gunn, is the overly controlled speech, a monotonous one. Gunn places two “boring” speakers, Senators Harry Reid and John McCain, on this end. Finally, strategically balancing the two extremes is Barack Obama, as described next.

Gunn uses Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton’s respective 2008 primary speeches as his main examples of controlled and uncontrolled speech. He showed how Obama managed to reference uncontrolled speech without falling into its trap himself. Obama had mentioned his reverend’s controversial and “incendiary” (Gunn’s term) statements regarding foreign policy—statements with which Obama himself disagreed. Gunn says that Obama “walks right up to the grunt in this speech, but doesn’t go all the way like his pastor did” (21). Overall, Obama successfully maintained balance between the two extremes to convince his audience of the command he has of speech. Clinton, on the other hand, lost control in her “Shame on You” speech, where she criticized Obama for his “attack” on her for presenting a universal health care plan. She fervently expressed her disagreement with Obama’s tactic and, seemingly with little control, cried “shame on you Barack Obama!” (23). In contrast to Obama, whose calm voice Gunn likened to Elvis Presley’s in “In the Ghetto,” Clinton comes across as “angry,” even shrill, as Gunn likens Clinton’s tone to the Wicked Witch of the West’s (24). As described next, however, Gunn identifies something much more situated as affecting the audience’s interpretation of Clinton’s speech—something beyond the content.

Gunn describes Clinton’s speech in another way: as an example of the uncontrolled representing femininity. He cites Lauren Berlant, who complicates the public/private sphere by arguing that social media and changing work roles (particularly for women) have produced “public intimacy” (6). Further evidence of the intimate/private becoming public is the attention given to private issues, including same-sex marriage and abortion (7). Since the noises and utterings of uncontrolled speech take place in the privacy of one’s own home, a domain traditionally allocated to women, women became associated with the physicality of uncontrolled speech. Gunn furthers this argument by mentioning Adriana Cavarero, who described the need of all children to individuate by separating from the mother, thus distancing oneself from the feminized body and voice (11-12). Lastly, Gunn describes Lacanian psychoanalytic theory as a factor in uncontrolled speech through parapraxes, “slips of the tongue, verbal missteps, and seemingly involuntary blurts” (15). Taking these concepts together, Gunn presents a more complex interpretation of the responses to Clinton’s speech, including the following: he contends that Clinton provoked fear in a (nagging) parent sort of way (24-25); failed “to perform femininity properly” (25); and sounded like the mother figure from whom the audience is attempting to separate.

Key Terms used throughout:

Austin: constative statement, performative utterance, illocutionary, and perlocutionary.

Butler: interpellation, Austin’s illocutionary and perlocutionary, and speech vs. conduct.

Gunn: uncontrolled speech and speech as object.

Connecting the readings:

The speech pieces this week connect in three ways. First, they all identify speech as an everyday object, not merely a tool for politicians. Austin describes speech as an “object” because we use it for all utterances we make. In fact, he attempts to establish a taxonomy for these everyday utterances throughout his lectures. Furthermore, Austin argues that many acts happen only if an utterance has preceded it (8); as such, the speech act is the thing that prompts the act, the doing. Butler also analyzes speeches, as well as gestures, as objects; these were apparent in her analysis of the court officials’ assertions and the burning cross, respectively. Finally, Gunn’s focus on journalists’ responses to politicians’ speeches shows his interest in everyday speech as object.

A second way in which these pieces connect is that they all demonstrate a switch from speech as meaning to speech as doing. Austin contends that “to say something is in the full normal sense to do something” (94). Butler acknowledges this point, too, when she says that “what is spoken in language may prefigure what the body might do” (10). However, Butler argues against Austin’s claim that words of the illocutionary act constitute “not only conventional, but in Austin’s words ‘ritual or ceremonial’” (3) because words’ meanings change regularly. As such, “[t]he illocutionary speech act performs its deed at the moment of the utterance” (2) but can’t promise that the word’s meaning hasn’t changed by the time its audience receives the message. In other words, the meaning of the words is unreliable; what’s worth analyzing is the action of what happens after the audience has received the message. The factor of time (past, present, and future), then, exists in Butler’s conception of the speech act. Overall, Austin’s perlocutionary act seems closest to what all three would agree to since it focuses on what’s not stated, on the consequences of the speech (i.e., the doing). Gunn provides a fitting example of this when he described Clinton’s audience as not hearing the speech (her arguments, standpoints, etc.), but as hearing her femininity. He maintains, “we don’t simply think in discriminatory ways, we hear in sex” (25). Gunn’s piece also serves as a fitting juxtaposition from last week’s Nixon pieces. In his assessment of Nixon’s speech, Hill assessed how Nixon presented his four plans to end America’s involvement in Vietnam. He focused on Nixon’s word choice—what was explicitly stated—to argue that Nixon pushed the audience to favor one of the plans over the others. By contrast, Gunn described what was implicitly stated in Obama and Clinton’s speeches to prove his point; he focused on what the speech did (the consequences of what the speakers said), rather than on the meaning of the words presented.

Finally, they connect because they all acknowledge that we can’t rely on speech doing what we expect it to do. At times (and often), we can’t control it. We see this played out in Austin’s perlocutionary act, where “what we bring about or achieve by saying something” can play out as persuasion, surprise or even deception (108). Butler, likewise, identifies the unreliability that arises with the speech act when she cites Shoshana Felman, who “reminds us that the relation between speech and the body is a scandalous one, ‘a relation consisting at once of incongruity and of inseparability’ … the scandal consists in the fact that the act cannot know what it is doing” (10). She furthers her discussion by stating, “Felman thus suggests that the speech act, as the act of a speaking body, is always to some extent unknowing about what it performs” (10). Her incorporation of Felman’s points certainly resembles Gunn’s argument about uncontrolled speech. The speech act, Butler contends, breaks down the mental/physical dichotomy (11), often in unexpected ways, and she explicitly states, “[m]y presumption is that speech is always in some ways out of our control” (15).

Centering Rhetoric:

The authors attended to rhetoric in two similar ways. First, they analyzed the consequences of a speech, rather than the speech itself. For instance, Gunn mentions how various journalists described Howard Dean’s scream (“battle cry,” “primal scream,” and “meltdown” [14]) and how many times news networks played the clip. For Gunn, these commentaries point to the public’s affective state, causing Gunn to call for a “reprivileging” (1) of pathos. Butler, likewise, argues in favor of moving beyond the speech; at one point, she said, “[t]he failure of language” is that it hasn’t “rid itself of its own instrumentality” (8). She then analyzed the consequences of speech in her analysis of the court case, where she pointed out how ignoring the historicity of language holds our society back from eliminating racism.

Second, they all seemed to reject agency as situated at its two extremes: it is neither complicit (and led by convention) nor sovereign (and fully reliant on the speaker), as displayed below.

Instead, agency seems to lie somewhere on the spectrum between the two. For instance, as Butler describes, “[t]he subject who speaks hate speech is clearly responsible for such speech, but that subject is rarely the originator of that speech” (34). Ultimately, the more we try to control speech (whether as an individual or as a society), the less agency the speech itself has to contribute.

While Austin, Butler, and Gunn all fit in the speech as object category, they do highlight rhetoric in different ways. For starters, Austin, a speech act theorist, doesn’t use the term rhetoric at all. However, his conception of felicitous and infelicitous outcomes do fit with the notion of persuasion. Butler explicitly uses the term rhetoric and emphasizes the importance of analyzing speech, particularly when language is injurious and when language “acts upon its addressee in an injurious way” (16). Her critique of the profession is that too much focus is placed on the language used, rather than on the effects that language has and how that language evolves or remains stagnant. Her whole book addresses how injurious language is “both rhetorical and political” (15). Gunn takes a deeply psychological approach to rhetoric. He argues for us to focus on uncontrolled speech in an attempt “to retrieve that affective or pathetic dimension of rhetoric that has been repressed” (5). For Gunn, the purpose of rhetorical criticism is to expose how rhetors address and even manipulate the public’s affective state.

In conclusion, Austin, Butler, and Gunn all view speech (as opposed to text) as an object of study, and they view spoken language as doing something, not just representing something. Despite some important differences between them, they all assert that speech isn’t necessarily the most genuine expression of the mind. In fact, speech often masks the actual message. Knowing this, they seem to challenge readers to read between the lines, so to speak, to search for the unstated messages that speeches are presenting.

Discussion Questions:

- What is speech as an object? How does this differ from our last unit?

- What examples can you provide of the perlocutionary act at play?

- How would you describe interpellation?

- What stood out to you from these essays that I didn’t cover?

Additional Sources:

- Adriana Cavarero, For More than One Voice: Toward a Philosophy of Vocal Expression, trans. Paul A. Kottman (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2005).

- Lauren Berlant, The Female Complaint: The Unfinished Business of Sentimentality in American Culture (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2008).

- Mari Matsuda, “Introduction,” in Words that Wound: Critical Race Theory, Assaultive Speech and the First Amendment, eds. Mari Matsuda, Richard Delgado, Charles Lawrence III, and Kimberle Crenshaw (Boulder: Westview Press, 1993).

- Shoshana Felman, The Literary Speech Act: Don Juan with J. L. Austin, or Seduction in Two Languages, tr. Catherine Porter (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1983).

Part 2: Sign

Introductory Materials on “Sign”

- Ferdinand de Saussure, “Part One: General Principles” in Course in General Linguistics, 65-98.

- Roland Barthes, “The World of Wrestling” and “Myth Today” in Mythologies, 15-25; 109-164.

- Anne Norton, “The President as Sign” in Republic of Signs: Liberal Theory and American Popular Culture, 87-122.

- Supplemental reading: Richard Harland, “Saussure and the concept of ‘langue’” and “Barthes and Semiotics” in Superstructuralism, 11-19, 52-64.

Ferdinand de Saussure understands language as non-referential. It is a theory of pointing, in that language is an indication of what the thing is. The term ‘c-a-t’ points not just to the thing, but to the category of the thing. Through the sign, the category of the cat is as real as the singular cat. What Saussure says is that (all meaning systems) are defined by relation, he means that the material world is unhinged from language. The vowel sound in ‘hat’ is defined by similarities between vowels as opposed to those between consonants. Your understanding of that sound is defined by that system of relationships’ opposition and similarity. All meaning is defined in the same way – at the level of meaning and not just at the level of consonants. All meanings are defined relationally, rather than absolutely. Where the scientific revolution was about laws, Saussure provides rules, not determinate but breakable.

Saussure is thus after a deep structure of rules for language. Although an infinite number of utterances are possible, the language system (langue) is a closed totality: "At every moment it is total and complete." Out of the production of signs emerges an infinite number of utterances. The Sassurian project is to derive linguistic rules (langue) from the utterances (parole)

- Parole: utterances or language in use.

- Langue: the underlying system or rules of language which are both finite and determinate.That is the condition of possibility for interpretation is the assumption of totality. Any given moment might have a different given totality.

At any synchronic moment (the momentary cross-section of linguistic relationships) langue is total and complete in itself. Language does not function by a system that exists outside of or before it, but constitutes its diachronic dimension: its longitudinal history of linguistic rules, relations, and transformations. The decisive contribution of The Course in General Linguistics is that 'the word isn't the thing.' Saussure shifts the point of focus from words to signs, and from a substantive to a relational theory of meaning in which the value of the sign is determined by its difference from other signs. Put differently, the value of the sign in the sign system is determined by its negative/differential relation to all the other signs operative in the system at that moment. No element has significance by itself. The significance of an entity or an experience cannot be perceived unless or until it is integrated into the structure of which it is a part. The world does not consist of independently existing objects (or referents) or in the things themselves (existential phenomenology. The sign comes into existence when the signifier is bound to the signified, or when the relationship between these terms appears fixed.

The sign is the conjunction of the signifier and the signified.

- The Signifier (sound-image)

- (t-r-e-e)

- (f-a-m-i-1-y)

- (w-o-m-a-n)

- The Signified (the concept, not the referent)

The relationship between signifier and signified is arbitrary, meaning that there is no necessary or inherent relationship between these terms. Why is it important that the relationship between signifier/signified be arbitrary? The arbitrariness of the sign means (1) that the signifier can change (2) By virtue of the fact that it's an arbitrary relationship, there is no necessary reason why the signifier should or should not change, and (3) Language is bigger than individual will, a change in the system cannot be willed.

Roland Barthes, on the other hand, theorizes myth. Myth is a semiological system of the second order that describes ideology as a recursive process of signification. The traditional notion of the sign as the arbitrary unity of the abstract signifier and a conceptual signified becomes a consolidated unit in myth. What is myth?

- " ... Myth cannot possibly be an object, a concept, or an idea; it is a mode of signification, a form." (109)

- "Mythology can only have a historical foundation, for myth is a type of speech chosen by history: it cannot possibly evolve from the 'nature' of things." (110)

- "Mythical speech is made of a material which has already been worked on so as to make it suitable for communication: it is because all of the materials of myth (whether pictorial or written) presuppose a signifying consciousness, that one can reason about them while discounting their substance. (110)

- " ... Myth itself, which l shall call metalanguage, because it is a second language, in which one speaks about the first. When he reflects on a metalanguage, the semiologist ... will only need to know its total term, or global sign, and only inasmuch as this term lends itself to myth." (115)

Sign as Object Presentation by Austin Fleming

- Ferdinand de Saussure, “Part One: General Principles” in Course in General Linguistics, 65-98.

- Roland Barthes, “The World of Wrestling” and “Myth Today” in Mythologies, 15-25; 109-164.

- Anne Norton, “The President as Sign” in Republic of Signs: Liberal Theory and American Popular Culture, 87-122.

- Supplemental reading: Richard Harland, “Saussure and the concept of ‘langue’” and “Barthes and Semiotics” in Superstructuralism, 11-19, 52-64.

Saussure, Barthes, and Norton develop the sign as object of rhetorical analysis. As a network of associative links, the sign moves rhetoric from occurring in a text, and instead at the level of culture. In doing so, semiology makes possible ideological critique, by identifying the employ of signs to mask history and naturalize the status quo. In this presentation I trace the development of semiology through Saussure, Barthes, and Norton before identifying the sign’s implications for the study of rhetoric.

Ferdinand de Saussure, Concepts of General Linguistics

Saussure is clear that language is more than a list of words equating to a list of ideas, but instead exists as a linguistic sign, which is “not a link between a thing and a name, but between a concept and a sound pattern” (66). Composed of a signal and signification, the two in concert form the sign as a whole. In practice, the two are connected such that the sound pattern “t-r-e-e” is linked to the tree as a concept forming the association as a whole.

The connection between signal and signification is arbitrary however, as there is nothing, for example, inherently treelike about “t-r-e-e.” The arbitrary nature of the linguistic sign is important, as it allows for signification to change over time. Saussure provides ample evidence for the evolution of language, noting such change is too complex to be initiated by any single language user immediately, and instead must occur over time when adopted by a multitude of speakers. Saussure therefore draws a distinction between linguistic structure, “the whole set of linguistic habits which enables the speaker to understand and to make himself understood” (77), and the linguistic community, who actually use speech at any given time.

Language, in its two components, may thus be studied in two ways: linguistic structure lends itself to diachronic analysis, or changes over time, and the linguistic community synchronically, or the static use of language across all users at any given moment. Saussure uses a chess board as a metaphor for the study of language. One can analyze the game diachronically by tracing the changing position of pieces over time, or synchronically by examining the potential moves available at each turn.

Saussure uses the chess metaphor to illustrate an important aspect of signs, in that their value derives from their relationship to other signs. The value of a chess piece depends on its relationship to the pieces around it, which is constantly changing as the position of the pieces move throughout the game. Signs hold value not because they are assigned a value, but because they stand in contrast to all other signs. Just as one move on the chess board may change the value of each other piece, one change in a sign’s value may change others by altering associations and relationships.

Roland Barthes, “Myth Today”

The purpose of Barthes’ project is to trace the ways in which history is erased in culture, that is the “naturalness with which newspapers, art and common sense constantly dress up a reality which, even though it is the one we live in, is undoubtedly determined by history” (10). Drawing from Saussure, Barthes uses semiology to illustrate this “naturalness” as specific type of speech: myth. Though identified as a type of speech, Barthes is sure to note that myth is not limited to just oral speech, as it is not limited by form or material. Myth is a second-order semiological system, in which the sign, composed of signifier and signified, become the signifier for a new sign. Myth is therefore a metalanguage, as it is language which speaks about language.

Barthes provides a (dated) example of myth in action:

I am at the barber’s, and a copy of Paris-Match is offered to me. On the cover, a young Negro in a French uniform is saluting, with his eyes uplifted, probably fixed on a fold of the tricolor. All this is the meaning of the picture. But, whether naively or not, I see very well what it signifies to me: that France is a great empire, that all her sons, without any colour discrimination, faithfully serve under her flag, and that there is no better answer to the detractors of an alleged colonialism than the zeal shown by this Negro in serving his so-called oppressors. I am therefore again faced with a greater semiological system: there is a signifier, itself already formed with a previous system (a black soldier is giving the French salute); there is a signified (it is here a purposeful mixture of Frenchness and militariness); finally, there is a presence of the signified through the signifier. (115)

Barthes provides further elaboration on how myth operates, and the purposes it serves. He further notes, “myth hides nothing” (120). It does not deny a history, it simply elides it. It is motivated speech, not arbitrary like the linguistic sign. It is interpellant in nature, directed at those who receive it. It transforms history into nature, cementing status quo as that which has always been. As depoliticized speech it speaks about reality, but denies the complexity of history that has shaped the present moment.

As myth is motivated to maintain the status quo, Barthes argues that it is ideological in nature. Drawing from Marxist principles, Barthes argues that myth serves to benefit the bourgeoisie. Myth, therefore, stems almost exclusively from the political right which holds a monopoly on the social institutions of human life.

Anne Norton, “The President as Sign”

Norton illustrates the symbolic function of the presidency, locating it in a network of signs which shape the ways in which the office is understood and operates ideologically. As a symbol, the president serves as a sign which may represent the electorate, nation, and their political party simultaneously, depending on circumstance, and subject to change with shifting contexts. Using Ronald Reagan and Franklin Delano Roosevelt as examples, Norton demonstrates the “variety of representative strategies made available to Presidents through the interplay of signifier and signified in the sign” (93), and revealing the complex history of personality traits and circumstance that help shape presidential history.

Reagan’s authority and reputation as president in part derived from his career in acting. Though he had not served in actual combat, he had portrayed it on screen, lending credibility to his calls for military action. Reagan’s self-aggrandizing bears resemblance to the boasting of Davy Crockett, frontiersman turned congressman. Reagan’s own boasting alludes to this history of the mythic Westerner, explaining the personal exceptionalism that allowed him to transcend from actor to president.

Roosevelt, with famously limited mobility due to polio, took office during the Great Depression. His prominent disability was analogous to the hardship the entire nation faced, and when he spoke of national recovery he could therefore be trusted. When the United States eventually emerged from the Great Depression, Roosevelt garnered comparisons to Lincoln, as the nation’s second savior.

As Reagan and Roosevelt illustrate, the office of the presidency holds meaning as a result of those who have previously held office, personality traits, and simultaneous political contexts. This is made possible as a result of the president’s visibility to the public, as the president is seen by the public they are able to see themselves reflected in the president “singular, united, with a common material form and a single will” (121).

Connection Between Readings

Saussure, Barthes, and Norton can be read chronologically as the development of semiology. As Saussure develops his theory of the sign, he envisions semiology as a new field of study which will continue to develop. His major contribution here is the sign itself, as well as the notion that signs derive their meaning from the relationship to one another. That is to say, a sign’s value is not because it positively means something, but because it negatively does not mean everything else. Existing in a network, a change in association of one sign may lead to a rippling change in all other signs.

Barthes’ theory of myth develops semiology by presenting myth as a unique type of signification. As a second-order signification, myth exists in a network of signs by chaining complete signs into the signifier for a new sign. Ideological in nature, Barthes uses wrestling to demonstrate the complexity of sign networks. Wrestling is a spectacle, in which nuance is set aside for monolithic display of suffering, catastrophe, defeat, good, and evil. That which is marked as good and evil takes on an ideological dimension via association with the wrestler who enacts it, as demonstrated by the American tendency to associate wrestling villains with communist imagery.

Norton further develops Barthes’ project of mythology with an extended case study of the American Presidency. If Barthes demonstrates the complexity of a Saussurean network of signs, then Norton shows the ways in which changes in this network have a rippling effect. The authority which the President holds is informed by the association with past presidents, personality traits, and current events.

Implications for Rhetoric

The sign as object is aligned with the view that rhetoric is something that is always occurring. Rhetoric exists at the level of culture in the form of ideology. Signs exist in a network, where meaning is simultaneously shaped and changed. As Barthes argues, signs are frequently employed ideologically to reinforce the current state of affairs as natural and devoid of history. Norton develops Barthes’ project to demonstrate the complex network of signs that allow the presidency as symbol to function rhetorically. By tracing the shifting associations of the office over time, Norton reveals that rhetoric is found at the sign.

Rhetoric at the level of sign thus lends itself to ideological criticism as it illuminates the series of associations that make up culture. This view stands in contrast to criticism methods which center the text hermeneutically. For example, the Hill-Campbell debate relies on interpretation of Nixon’s speech to determine its effectiveness. Located within the text, Nixon’s speech is judged for the effect it may have on an audience. In comparison, Norton employs sign to locate Nixon’s rhetorical function as president not in a singular text, but in the wider cultural understanding of surveillance.

The sign as object presents new possibilities for methodology in terms of ideological criticism, but what also may be object of study. No longer rooted strictly in the symbol, anything can function rhetorically as a sign, and thus rhetorically as well.

Discussion Questions

- How does sign as object figure into our ongoing discussion of rhetoric as epistemology and ontology?

- How does the sign align with our agreed definition of modernity?

- Saussure, Barthes, and Norton describe the psychological associations of the sign, but are vague as to how conscious this association is. How might we understand the role of affect in semiology? Are sign associations affectual or rational?

- Barthes argues that “statistically, myth is on the Right (150). Though he is clear that the Left is capable of employing myth, he argues that it is rare as the left is aligned with the oppressed, and seeks to make the world, not mask the relations within it. Should worldwide balance of power flip, is it possible for this relationship to flip? Might we envision a world in which the left are the primary employers of myth?

Related Readings

- Barthes, Roland. 1977. “Rhetoric of the Image.” In Image, Music, Text.

- Fisher, Mark. 2009. Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? Winchester: Zero Books.

- Greenwood, Michelle, Gavin Jack, and Brad Haylock. 2018. “Toward a Methodology for Analyzing Visual Rhetoric in Corporate Reports.” Organizational Research Methods, 1–30. doi:10.1177/1094428118765942.

- McGee, Michael Calvin. 1980. “The ‘Ideograph’: A Link Between Rhetoric and Ideology.” The Quarterly Journal of Speech 66: 1–16.

Part 3: Persona

Presentation by Ryan Wold

Introductory Materials on “Persona”

- Edwin Black, “The Second Persona,” Quarterly Journal of Speech 56 (1970): 109-119 and Celeste M. Condit, “Pathos in Criticism: Edwin Black’s Communism-As-Cancer Metaphor,” Quarterly Journal of Speech 99 (2013): 1-26.

- Phillip Wander, “The Third Persona: An Ideological Turn in Rhetorical Theory” in Central States Speech Journal 35 (1984): 197-216.

- Supplemental reading: Phillip Wander, “The Ideological Turn in Modern Criticism,” Central States Speech Journal 34 (1983): 1-18.

- Charles Morris IV, “Pink Herring & the Fourth Persona: J. Edgar Hoover’s Sex Crime Panic,” Quarterly Journal of Speech 88 (2002): 228-244.

- Lisa Ede and Andrea Lunsford, “Audience Addressed/Audience Invoked: The Role of Audience in Composition Theory and Pedagogy,” in National Council of Teachers of English 35 (1984), 155-171.

The theory of persona refers broadly to an important theory of audience that has been conceived within the public address tradition of rhetorical scholarship. The theory of persona has evolved with changing notions of rhetoric and its situations. Within this framework, rhetoric is to persona as public address is to the audience of that address.

- The First Persona “is the author implied by the discourse.” It refers to the assumption that the speaker is made manifest in the text of the public address to an audience, or that some trace of the rhetor’s intention, history, or psychology is legible in a given instance of public address. Focusing upon the first persona is typically a sign that the analysis foregrounds a rhetor-centered agency insofar as the rhetor exercises a determining influence over the speech and its possible interpretations.

- The Second Persona is “the implied audience for whom a rhet constructs symbolic actions.” Put into different language, this is who the audience ‘ought to be,’ the image of the collective addressee that imputed by the text of the public address. If there is a ‘we’ implied by the rhetor or their discourse, then this constructed ideological common ground is an audience that is brought forth by rhetoric. Considered alongside the preceding units on speech (particularly its emphasis on interpellation) and the sign, the second persona also involves a concern with constitutive rhetoric, or speech/text that, through the act of self-naming, hails a social new kind of subject into the world. Against Black’s logo-centric conception of this process, Condit argues that audiences are constituted at the level of pathos, emotion, and visceral feeling, and that this mode of address does the work of ideology in a way that rhetorical critics have yet to seriously consider.

- The Third Persona refers to the “audiences not present, audience rejected or negated through the speech and/or speaking situation.” In Kenneth Burke’s terms, this would be the ‘no’ implied by the speech, a negative that is both necessitated by and rejected from the vision of presumptive unity given to an audience by an instance of public address. Recalling the analysis of the “Coatsville Address,” Black’s work revised neo-Aristotelian assumptions regarding who a possible audience might be for a given rhetorical discourse. The “second persona” continues this work by stressing the ‘moral importance’ of discovering those audiences brought into being by ideologues. Wander argues that this moral importance ought also be understood in terms of those excluded by discourse.

- The Fourth Persona “is an audience who recognizes that the rhetor’s first persona may not reveal all that is relevant about the speaker’s identity, but maintains silence in order to enable the rhetor to perform that persona.” The fourth persona is a split act of public address -- it is audible to everyone at one level of ‘meaning’ but only audible to a select group at another level: that of the “textual wink” that takes the form of a doubled reference. Related to the Fourth Persona is the eavesdropping audience attributed to Gloria Anzaldua, which “is an audience whom the rhetor desires to hear the message despite explicitly targeting the message at a different audience.” This can be for two reasons: (1) To limit room for response by, or the agency of, the eavesdropping audience, or (2) to allow the eavesdropping audience to feel empowered because they are not being criticized even as they hear criticisms made against others.

Introduction

In these articles we find the explanation of the second, third, and fourth personas in their original context. By developing these concepts the authors provides rhetorical critics with a framework for making moral assessments of discourse. These readings also help us move beyond criticism that focuses solely on the author and the text. The concepts of the third and fourth personas guide us to think about and evaluate what is not said, and how that silence relates to everything else going on in the world outside of a particular text. Together these five readings clarify the role and complicate the responsibility of rhetorical critics.

Edwin Black, “The Second Persona”

Black opens his essay by firmly stating that moral evaluation of rhetorical discourse is important and necessary. He describes the duty of academics and critics as giving order to history and believes accomplishing that task is only possible with the help of moral judgements. However, he claims we have fallen short of this duty due to the discomfort about making such judgements. He writes, “We are accustomed to thinking of discourses as objects, and we are not equipped to render moral judgements of objects.” (p.110) The unspoken premise of Black’s claim is that critics, and humans in general, are accustomed to making moral claims about people, not objects. From this starting point it is helpful to understand Black’s essay as a journey from viewing rhetorical discourse as an object to viewing a person(a) within the discourse which Black believes is necessary in order to overcome the discomfort of making moral judgements of objects. In order to make the transition from the neutrality of an object, a concept Black attributes to Aristotle, Black introduces the concept of the second persona and argues for the moral significance of that persona.

Before introducing the second persona Black introduces the first persona which he describes as “the implied author of a discourse.” (p. 111). Citing the way camera and makeup crews transform the person of Ronald Reagan into an ideal persona for a given situation he demonstrates how the first persona can be constructed. He moves quickly passed the concept of the first persona to the second persona writing, “What equally well solicits our attention is that there is a second persona also implied by a discourse, and that persona is its implied auditor.” (p. 111). To underline the idea that the implied auditor does not necessarily have anything to do with the actual (addressed) audience that hears a discourse he explains that you can identify the implied audience of a discourse even if you are the only person to ever read a speech that you find in a closet.

Black believes ideology to be inseparable from a persona. He uses Marx’s definition of ideology here, “The network of interconnected convictions that functions in a man epistemically and that shapes his identity by determining how he views the world.” Black then goes on to claim that you can identify the implied ideology of an audience by “stylistic tokens” in the discourse. He uses the example of the phrase “bleeding heart”. If someone uses that term when talking to the audience the audience has to decide whether or not they identify with the kind of person, the ideology of a person, that would describe liberals as “bleeding hearts.” Black’s argument regarding moral assessments of discourse hinges on this idea of identification. Regarding the purpose of human life in modern times he writes “The quest for identity is the modern pilgrimage” (p. 113). This claim leads Black to give major moral significance to the audience’s choice as to whether or not to identify with the persona of the implied auditor constructed in any discourse.

As an illustrative case Black uses the Blue Book of the John Birch Society, a manifesto written for a right wing anti-communist group written by Robert Welch. Black focuses on Welch’s use of the cancer metaphor for describing communism as an example of how Welch constructed a persona of a person that has puritanical attitudes toward their bodies, ambivalence toward nuclear war, reverence for private property and personal agency, and guilt. Black suggests that whether or not you agree with the text of the book is really a choice of whether or not you identify with the implied persona. Condit later exposes Black’s misreading of the Blue Book, hypocritical self-righteousness and over application of the cancer metaphor, but nonetheless Black’s explanation of the second persona made a substantial contribution to rhetorical studies.

Celeste Condit, “Pathos in Criticism”

Condit’s major contribution to the discussion regarding persona originates in her explanation that it is not ideology alone that is responsible for inspiring action. She refers back to Aristotle’s treatment of emotions to support her argument, “Ideology in isolation does not guide public action, but rather the forces that Aristotle described under the heading of pathos are also influential in public discourse and its effects” (p. 3). Condit explains the key weakness in Black’s argument is that he focused too much on the power of ideology and neglected pathos.

Condit defines pathos as, “the deliberative art for the construction of shared public emotion” (p. 3). She argues that the emotions stirred in an audience by a speech do not necessarily align with a coherent ideology. Black misstepped by treating ideologies as if they are coherent, all-encompassing entities that dictate a person’s every action. By simply identifying the inconsistencies in Welch’s ideology Condit shows the ineptness of Black’s assumption.

Taking the highroad, Condit is intentional to credit Black’s contributions to the field. However she warns that if, as critics, we fail to consider our own emotional positionality and cultural and social affiliations we may follow in Black’s footsteps. Condit cautions not to treat Black as a scapegoat, “We are all prone to Black’s errors, due both to our shared emotional predispositions and to our participation in a community of discourse-focused critics” (p. 7).

Condit dedicates much space to carefully exposing Black’s misreading of Welch and misinterpretation of the cancer metaphor. For example Black argued that Welch used the cancer metaphor due to the incurability and sense of doom associated with cancer, and insisted that fear was connected to the right’s casual approach to nuclear war because the implied audience believed they were doomed regardless. Condit dismantles Black’s argument by showing specific examples of Welch calling for less military spending and making optimistic declarations about the future of the country.

After critiquing Black’s reading of Welch, Condit still acknowledges the harmful yet effective components of Welch’s and Black’s rhetoric and concludes by writing, “Taken together, these various findings indicate that coherence between ideology and pathos is not necessary for rhetoric to be effective, or even laudable on other grounds” (p. 21).

Phillip Wander, “The Third Persona”

Wander’s description of the third persona comes toward the end of a lengthy essay in which he is responding to critics of his previous essay “The Ideological Turn.” Wander, similarly to Black, believes that critics should make socially, morally, and politically significant arguments in their work. Wander comes to the creation of the third persona in response to arguments that his ‘ideological turn’ pulls discourse that some critics and even the authors claim to be apolitical into the realm of the political and moral. Specifically, Wander is trying to answer the question, “Where does the critic get permission to link events in the material world with the ideas in a speech when the speaker does not refer to or may even deny the relevance of such things in the speech?” (p. 208). To answer this question Wander creates the third persona, “This link calls for an augmentation of the concept of audience in rhetorical theory to include audiences not present, audiences rejected or negated through the speech and/or the speaking situation. This audience I shall call the Third Persona” (p. 209).

Wander uses Heidegger’s 1933 lecture on art to illustrate the presence of the third persona. Those critical of Wander’s claims questioned how a lecture about esoteric ideas of time, being, and art could be related to the political conditions of Germany at the time. Wander makes the connection by stating that if we believe an audience member could make the connection between discussion of fine food and the experience of starvation then you are on your way to seeing how Heidegger’s lectures on art and being relate to the atrocities being committed by the German government outside the lecture hall in which he spoke (p. 210). Wander’s idea of the third persona moves beyond the rhetor and the audience and considers the totality of the world, the public space in which discourse takes place and all those affiliated with that public space. Wander emphasizes the high moral standard he imposes by encouraging critics to consider the third persona as he dramatically ends his essay with the following sentence, “Properly understood, it involves the unity of humanity and the wholeness of the human problem” (p. 216).

Charles Morris IV, “Pink Herring or Fourth Persona”

Morris’ article centers on the rhetoric of J. Edgar Hoover’s passing performance and how such performances create a fourth persona. Morris describes passing as “succeed[ing] in veling one’s identity, i.e., convincing certain audiences of an ‘acceptable’ persona” (p. 230). Morris then distinguishes social passing from rhetorical passing. He defines social passing as convincing everyone that a person is something they are not, whereas with rhetorical passing creates “one audience that’s ignorant and another that knows the truth and remains silent about it” (p. 230). The fourth persona is the audience that knows the truth, but stays quiet about it. It resembles the third persona in that both come into existence through silence.

In some passing performances, Morris explains, the rhetor may try to break the silence and “wink” at the audience of the fourth persona in hopes of a cooperating audience. Such as, “an implied auditor of a particular ideological bent, presumably one who is sexually marginalized, understands the dangers of homophobia, acknowledges the rationale for the closet, and possesses an intuition that renders a pass transparent” (p. 230). However, due to Hoover’s prominent position and long list of enemies he was desperately afraid of having his sexual preferences revealed by ‘menacing clairvoyants’ of the fourth persona. Thus he decided to implement policies aimed at silencing the fourth persona via persecution. Instead of winking at the audience he aimed to destroy the audience. Although Hoover’s actions were despicable his fears were legitimate. Morris quips, “The motto of the fourth persona: it takes one to know one” (p. 240).

Ede and Lunsford, “Audience Addressed/Audience Invoked”

Ede and Lunsford’s article is a little removed from the critical theory conversation of the previous four articles as it stems from writing studies. It is still very relevant to the conversation though. They start by asking what is the best way to teach writers about audience. If we over-emphasize audience it leads to pandering and disregards truth and good reasons; if we over-emphasize objectivity or the elusive notion of ‘good writing’ we miss out on the importance of context. To answer this question Ede and Lunsford explore a couple different ways of thinking about and teaching the concept of audience.

First they look at the idea of the ‘audience addressed.’This focuses on the actual material audience that will hear or read the text. They wrote, “Those who envision audience as addressed emphasize the concrete reality of the writer’s audience; they also share the assumption that knowledge of this audience’s attitudes, beliefs, and expectations is not only possible (via observation and analysis) but essential” (p. 156). Since such observation and knowledge is not always possible they move to explore other ways of thinking about audience.

The second idea they explore is ‘audience invoked.’ Ong’s claim that, “The writer’s audience is always a fiction” epitomizes this approach to thinking about audience. The invoked audience is the idea of an audience the writer constructs as they write and the writer can never know for sure whether or not their idea of the audience is accurate. They don’t know who their text will reach.

Ede and Lunsford also point out that the writer is repeatedly the first audience of any text as they read and reread their writing. Ede and Lunsford don’t land on any particularly partisan conclusions, and instead opt for a favorite among rhetoricians, an emphasis on context, “One way to conceive of ‘audience’ then, is as an overdetermined or unusually rich concept, one which may perhaps be best specified through the analysis of precise, concrete situations” (p. 168).

Connecting the Readings

The readings come together to create a great foundation for our understanding the rhetorical concept of persona. Black’s article brings the concept of persona front and center as he conceptualizes the idea of the second persona. Black’s move shifts the focus from the rhetor and the text as an object to an abstract concept of audience. The titles of the Wander and Morris articles alone reveal that they are in conversation with Black’s work. Beyond the obvious connection of moving from a second to a third and fourth persona it is important to see how Black’s move to step away from just the author and the text quickly led to a step that considered all of the world. Where Black looked for small hints of what is present to make conclusions about a certain implied audience Wander looked for hints about what was missing to make conclusions about the whole rest of the world. Black opened the door for critics to explore what is not said and what is not written.This open door led the way to important discoveries such as Morris’s where he was able to identify the persona and the portion of the audience that is present but silent.

These articles also share similarities in that although they focus on audience in terms of methodology they are remarkably critic-centric. The articles we read for this section each made commendable contributions to the field as they made strong arguments for critics to produce morally and politically engaged scholarship. Despite those positive contributions it appeared that none of the authors needed to leave their office in order to make these contributions. This demonstrates the difference between reception theory and persona theory. Where reception theory calls for engaging with the audience and finding out how audiences actually act, persona theory makes no such demands upon its practitioners. Black’s paper provides a great example of the risks associated with this type of armchair theorizing. In the article he claims that he can identify the implied ideology by a simple ‘stylistic token’. From the presence of ‘bleeding heart’ he develops a whole theory about a person’s ideology and actions. This can dangerously lead to stereotyping and false conclusions. As the pace of change increases it is becoming harder and harder to pindown the meaning of ‘stylistic tokens.’ Just five years ago in my undergrad education using “he/she” in academic writing was a symbol of progressivism and female inclusion whereas today it might be interpreted as a ‘stylistic token’ linked with conservative ideology and a commitment to binary definitions of gender. Condit’s critique of Black symbolizes how easily the conclusions made with persona theory can be overapplied or simply wrong.

Centering Rhetoric

This set of articles adds an important contribution to the conversation about what is rhetoric. They succeed in providing a framework for assessing the moral quality of particular pieces of rhetoric, but they fall short of answering the ancient question about whether rhetoric itself has an intrinsic moral value. Black’s explanation of the second persona and the moral decision each member of the audience has to make regarding identifying with that implied persona provides an answer to the debates we’ve had in previous classes about whether or not you can judge the moral quality of discourse. Black wrote, “We are solicited by the discourse to fulfill its blandishments with our very selves. And it is this dimension of rhetorical discourse that leads us finally to moral judgment” (p. 119). Yes, we can and should make moral judgments about discourse.

Condit adds to this conversation and to the profession of rhetorical criticism by reminding us of the importance of evaluating our own affiliations and emotional positionality. By highlighting the flaws in Black’s argument she provides an exquisite snapshot of how failing to reflect on our own affiliations can lead to misguided moral proclamations. Wander’s and Morris’ contribution of additional personas to complement Black’s initial idea provide more tools to guide the moral judgements of rhetorical critics.

Despite the fact that Black makes an intentional effort to move away from the idea of rhetoric as a neutral instrument, his assessment of Welch’s rhetoric leads us back in that direction. Both Black and Condit identify aspects of Welch’s rhetoric that was effective even though they consider the rhetoric to be morally flawed. Morris also considers some of J. Edgar Hoover’s tactics to be effective. Although These authors provide us with tools for assessing morality we still have not escaped the problem that has always haunted rhetoricians- as a discipline we still mark discourse that inflicts major pain on humanity as effective.

Discussion Questions

- In Wander’s essay regarding Heidegger’s poems he makes a great argument for the critic’s right to make links between a text and a things that are not mentioned in a text. Is there any limit to what can be linked to a text? Should there be a limit? Does every text have a third persona? Is a Super Bowl commercial ever just a Super Bowl commercial, or is it always related to the #metoo movement, the war in Syria, global warming, etc?

- How does the moral judgment of discourse relate to the effectiveness of discourse?

- What questions will persona theory allow you to answer in your research?

Additional Readings

- Catherine Helen Palczewski, Richard Ice, John Fritch, “Rhetoric in Civic Life”, Strata Publishing Inc. (2016)

Designed as an undergrad textbook this provides accessible definitions of the four personas.

- Angela Gonzalez, Elizabeth Weiser, Brian Fehler, “Engaging Audience: Writing in an Age of New Literacies”, National Council of Teachers of English (2009)

This is an anthology commemorating 25 years since Ede and Lunsford’s publication of Audience Addressed/Audience Invoked and it includes an essay with their updated vision of audience titled “Among the Audience: On audience in an Age of New Literacies”

- Erin Fries, “Personas as Rhetorically Rich and Complex Mechanisms for Design” in Rhetoric and Experience Architecture edited by Liza Potts and Michael J. Salvo