The Signifier

The Freudian-Lacanian Tradition

- Sigmund Freud, “The Dream-Work” in The Interpretation of Dreams, 211-236.

- Supplemental reading: Richard Harland, “Lacan’s Freud” in Superstructuralism, 33-41.

- Supplemental reading: Atilla Hallsby, “Psychoanalysis and Critical/Cultural Studies,” in the Oxford Resource Encyclopedia, 1-36.

- M. Jimmie Killingsworth and Jacqueline S. Palmer, “The Discourse of ‘Environmentalist Hysteria’,” Quarterly Journal of Speech 81 (1995): 1-19.

- Diane Davis, “Identification: Burke and Freud on Who You Are,” Rhetoric Society Quarterly 38 (2008): 123-147.

Signifier/Letter

- Jean-Luc Nancy and Phillipe Lacoue-Labarthe, “The Logic of the Signifier” in The Title of the Letter: A Reading of Lacan, 27-86.

- Supplemental Reading: Bruce Fink, “Reading ‘The Instance of the Letter in the Unconscious’,” Lacan to the Letter: Reading Écrits Closely, 63-105.

- Primary Text: Jacques Lacan, “The Instance of the Letter in the Unconscious, or Reason since Freud” in Écrits, 412-444.

- Shoshanna Felman, “Renewing the Practice of Reading, or Freud’s Unprecedented Lesson,” and “The Case of Poe” in Jacques Lacan and the Adventure of Insight: Psychoanalysis in Contemporary Culture, 19-52.

- Primary Text: Jacques Lacan, “Seminar on The Purloined Letter,” in Écrits, 6-50.

Applications

- Joan Copjec, “The Unvermögender Other: Hysteria and Democracy in America” in Read My Desire: Lacan Against the Historicists, 142-161.

- Diane Rubenstein, “The Mirror of Reproduction” in This is Not a President: Sense, Nonsense and the American Political Imaginary, 1-49.

- Kaja Silverman, “Liberty, Maternity, Commodification,” new formations 5 (1988), 69-89.

Introduction

This week, we consider the psychoanalytic account of the signifier as a unique method for rhetorical theory. The reason that this is situated here as method is that psychoanalysis is a method or technique developed for the specific purpose of alleviating the subject’s trauma. It is a way of reading the patient’s speech for its conspicuous markings, with the express goal of resignifying the past or at least revealing the contingency of affective commitments. These commitments take the form of fixed or stubborn significations; the tools of psychoanalysis help us to describe how they are unfixed or loosened. Ultimately, this is because in psychoanalysis, it is not the subject or meaning that is most important or exercises control over the signification of their speech. Instead, the signifier has its own agency which exercises a measure of control over the subject.

The question that separates the Freudian from the Lacanian tradition is “where do we find the signifier”? In Freud, we find it in the dream-work, and more specifically, in the mechanisms of condensation and displacement. With Lacan, we find it in discourse, which is both the patient’s ‘talk’ in session and the ‘talk’ that circulates in public settings, broadly construed. Consequently, we can today claim to find the unconscious either by analyzing discourse in a way that resembles Freud’s interpretation of dreams, or by recognizing (w/ Lacan) how the unconscious is “on the outside,” in the speech that the subject adopts as their own, although it long precedes and long outlasts the subject who comes to it. The acquisition of language, understood as the entry into the symbolic, is traumatic and produces the subject as the site of a loss -- although this loss could not exist without the intervention of language. More precisely, we would not know that we had lost something unless a signifier intervenes to name this pre-verbal plentitude.The signifier is particularly important for understanding Lacan’s method. His major rhetorical terms are metonymy and metaphor (mapping loosely onto displacement and condensation) which describe a patterned relationship between signifiers. Metonymy describes a kind of slippage among signifiers, a looseness that links them together like the “hands” and the bodies of sailors in the phrase “all hands on deck.” For instance, psychoanalysis is known for the theory of the superego, the big-O Other, and the Father, all of which describe a position of authority that exercises repressive control over the subject. (Folks like Zizek will equate such positions with capital). There is a metonymic relationship among these signifiers insofar as they are only loosely associated but there is a kind of slippage among/between them. Metaphor describes a signifier “with substantial gravity” that binds a metonymic series together, retroactively. In other words, we don’t always know the connections or links between different signifiers until a “master-signifier” binds them together, bringing their precise hierarchy into focus. Jacques Alain Miller describes the patient in session who says the word “love” may/will not mean the same thing by this term as any other patient; we must interpret for just that one particular case. However, the meaning of “love” for that patient -- whether traumatic, abusive, romantic, etc -- will come into focus retroactively, after the fact, once other signifiers have allowed it to crystalize as a point “with substantial gravity.”

The terms signifier, objet petit a, and the (purloined) letter are similarly bound up in a metonymic connection to one another, and on the surface would appear to refer to similar linguistic concepts. Each serves a different function, however. The signifier is theorized as a correction to Saussure’s theory of the sign, which no longer depends on meaning, but the way that the signifier slides from one meaning to the next. The objet petit a describes the “object of desire” and the “object of the drive” under different circumstances, but refers ultimately to an arbitrary site of the subject’s attachment. The letter is an allegory for the connection among the real, symbolic, and imaginary, and how a signifier creates different attachments for different subjects. In Lacan’s view, communication occurs very rarely, in the sense of an exchange of meaning. Instead, there is an exchange of signifiers which mediate an absolute division between the desire of the subject, the desire of the other, and the way each imagines their opposite.

Lacan also leverages a number of other concepts that have importance/relevance for rhetorical studies. These include the registers of imaginary, symbolic, and real.

- The imaginary is the locus of representation and the register where signifiers are connected contingently to a signified and referent. It is also the site of the “want to be,” or the aspirational/despised self, to which the subject makes an emotional attachment. In the chess metaphor employed earlier in the seminar, the imaginary are the individual, moment-to-moment moves.

- The symbolic is the site where the subject’s identity and desire are organized as a patterned attachment. Lacan describes it as a linguistic network, automaton, or machine where the subject is fed into a circuit. In the chess metaphor, the symbolic is ‘the rules of the game,’ the limited moves that are available and their finite permutations.

- The real is the condition of possibility for a complete reconfiguration of the symbolic and imaginary registers; it is a disruption or hole in the symbolic order that undermines and undoes an established network of connections among signifiers. In the chess metaphor, it is when the table is flipped, and the rules are changed from mathematical permutations into a more literal violent conflict.

Like metonymy and metaphor, these concepts have been leveraged to advance critical goals that are similar or in harmony with those of rhetorical studies. The collected readings seek to provide an account of how that harmony can be achieved, as well as how the above described concepts can be mobilized as a systematic critique of public discourse.

Part 1: The Freudian-Lacanian Tradition

Diane Davis, “Identification: Burke and Freud on Who You Are,” Rhetoric Society Quarterly 38 (2008): 123-147.

Davis expertly threads together similarities and differences between Burke and Freud’s understanding of identification to explore the ever-burning question: who are we? How are we who we are? Her scholarship helps us better understand socio political situations (easily applicable to the environmental movement and climate change debate, which we will discuss in the following readings), the players within them, and how individuals and groups do or do not identify with each other for the betterment or endangerment to society.

Similar to Freud, Burke set out to expose human motivations by analyzing language (124). They both describe identification as a social act that “partially unifies discrete individuals, a mode of symbolic action that resides squarely within the representational arena (125). However, Davis establishes a few important differences in their understandings of identification.

Burke brings in the psychoanalytic assumption that we are separate subjects who do not openly transact information. For Burke, we are separate human beings (A and B) who do not share an essence and are not conjoined in any sense: “there is no essential identity; what goes for your individual substance is the incalculable totality or your complex and contradictory identifications through which you variously become able to say ‘I’” (127). Thus, we need rhetoric as a “mediatory ground” to connect A to B. Here, Burke frames rhetoric as a courtship more than a duel (125). But it is not as simple as A relating to B, and therefore becoming identified with B. A sees something of themselves in B. That projection of ourselves on to the other allows us to see something of ourselves in someone else. The biological separation, the state of nature that we are in fact physically separate human beings, is always there, but through communication we can recognize something of ourselves in others, and therefore relate to them. This act reinforces a sense of identification that tricks us into thinking that there is a connection even though, for Burke, we are separate.

For Freud, the infantile subject is very important. He maintains a “clear distinction between desire and the purely secondary motivation of identification: Boy wants Momma, Daddy has Momma, so Boy wants to be Daddy, identifies with him, takes him as the ideal model” (124). Freud argues that the infant subject doesn’t see any difference between their body and the rest of the world; between the infant’s body and the mother’s body. It is not until we experience the absence of the breast that we realize we are fundamentally separate from each other. This loss of connectedness is traumatizing and forces us to come into our identity.

Burke aligns with Freud’s reasoning that humans are motivated by desire but argues that “the most fundamental desire is social rather than sexual, and that identification is a response to that desire” (124-125). By establishing identification as a social phenomena instead of a sexual one, Burke is able to enter the world of politics. Davis points out a tension in Burke’s theory of identification. Burke establishes that we are separate beings that identify with each other when we see something of ourselves in the other. But he also explains that we are actors, “enacting roles that are available to me (us) as a member of a group, which is the only active mode of identification possible” (127). If our identities are the product of an identification with figures or symbols that reside outside ourselves, then we are always already other than ourselves (127). Burke insists that the subject, the wax, is “both estranged and knows it is estranged, which allows him to interpret identification as an active response to passive estrangement...an estranged and desiring individual holding steady beneath the swirl of identifications” (132).

Davis debunks Burke’s theory of divisiveness by introducing research on mirror neurons in our brains that fire off not only when we do something but also when we see someone doing something--they resonate in my brain when I see you move (131). It is not only that “I” am hardwired to mime your actions, but “I may be your actions, that there may be no me until I perform you” (132). Davis argues that humans cannot be characterized as divisive if we cannot consistently distinguish between ourselves and others (131-132). While this shatters the presumption of Burke’s biological disconnect, it aligns with his theory that we are all actors, acting each other.

Similar to acting each other, Freud argues that we eat each other, stating, “you are who you eat” (134). However, Freud theorized that the ego is formed “directly and immediately” through primary identification which precedes the very distinction between ego and model. He states that “the effects of the first identification made in earliest childhood will be general and lasting” (134). Whether identification occurs blindly and immediately at birth as Freud suggests or through communication and association between separate organisms as Burke argues, a big question remains: can we overcome our identifications? Or as Freud puts it, “is there any way retroactively to switch off the swallowing machine” (136)?

Burke insists that identification is a symbolic act, and therefore it is available for us to critique (127). Even though identification makes it possible for people to come together, Burke views it as more dangerous than optimistic--especially when identification goes out of control. He recognizes that too much identification can lead to war. The real challenge is for people to learn how to resist and distance themselves from identification, which is ontologically guaranteed (126). “The problem, then, is not with identification (trust, faith) per se, but with faulty or malign identifications, which must be exposed, critiqued, discarded, and replaced with sounder loyalties” (126). This is where suggestion and hypnosis come into play.

Suggestion, a synonym for hypnosis, names the power of an “influence without logical foundation” (137). It is the birth of a subject or an idea that takes root in the brain and “not examined in regard to its origin” (137). It has the power to put people into motion, even without the use of words, based on our associations and expectations. It may be challenging in our current state of utopia, but let’s try to imagine there is a unifying figure that leads people with a false image of reality. Some people identify with that leader--they see something of themselves in them. This group of people is so hypnotized and influenced by the unifying figure that even when that figure falls (#2020) the group’s sympathetic bond of identification remains. “This untrying tie forms an identification from the withdrawal” (144). The ideology lives on-- ”persuasion without a rhetorician...produced in the absence of any direct suggestion” (140).

Davis articulates that the power of suggestion, our capacity to be “directly and immediately induced into action” without logical foundation, takes place “behind the back and beyond the reach of critical faculties” (140). This challenges Burke’s idea that we could feasibly secure a crucial distance between self and other through reasoned critique or other forms of symbolic action (142). According to Freud, “persuadability operates irrepressibly and below the radar of critical faculties” (144). This leaves a sorrowful feeling in the reader (me) that there is little hope for collaboration or unification in the environmental movement. However, the following articles provide insight into how things could be better; how the scars we have made on the earth (that we have repressed and turned away from), may bubble up to haunt us in the conscious light of day.

Sigmund Freud, “The Dream-Work” in Interpretation of Dreams, 211-236.

Freud investigates the relationship between the manifest dream-content (the actual imagery and events of a dream, and the latent dream-thoughts (the unconscious wishes of the dreamer). He argues that “it is from this latent content, not the manifest, that we worked out the solution to the dream” (211). Freud argues that, through procedure (dream work), we can identify how and why the actual dream reflects our unconscious.

Let’s take a dream that I just had (time stamp, Thursday, April 11, 7:58am) as an example (real dream). I was walking through the lobby of a brightly lit building with high ceilings and an open layout. People bustled around purposefully like they had just finished their first cup of coffee but hadn’t started the sad demise of their second cup--a happy buzz. I was walking with Kristiana, a friend and colleague of mine at UMN. I don’t remember what we were saying to each other, but we were making some sort of small talk as we walked to the bathroom. I sit on the toilet in a stall with red doors, still chatting with Kristiana. I look down and just outside of my bathroom stall I see a blanket on the floor. It is the same blue and green blanket with large flower prints that I meticulously picked out when I proudly got my own room in 6th grade. I wondered why Kristiana had my blanket before howling wind woke me up. I lay motionless in bed, wondering if the wind was somehow strong enough to blow my canoe out of the yard, decided today was definitely a leggings day, and got up to finish this paper.

Freud explains that our dream worlds are over coded because the world we are living in is too much to handle. Our dreams compensate for that by coding our dreams, littering the dream world with symbols and representations to protect us from difficult thoughts or realities. For example, in my dream, the building we were in was unfamiliar, but I can assume it was meant to be school based on the fact that Kristiana was there. I think the bathroom stall represents me wasting time, because I often linger to escape the world in the four flimsy half-walls of a stall. Just that night sat on the toilet looking at instagram for a while before I heard a “hello?” from John in the other room, confused about where I had gone during our bedtime routine. The blanket from my dream is the same blanket that I had draped over my shoulders in my home office while I was writing this paper last night until I discovered we still had place and bake cookies and then forget what exactly happened in the seventh season of Game of Thrones and decided that folding laundry while watching GOT and eating cookies might be a really good use of my time until 1:00am rolled around I realized that really John Snow is really Dany’s nephew (what’s gonna happen you guys?) and that I hadn’t even started my Freud summary yet.

It is fairly easy to see the latent dream content (unconscious) at play in my manifest dream-content. In Freud’s procedure, we would start out by talking about the dream thoughts that often “reveal themselves to be a complex of thoughts and memories with the most complicated structure, having all the features of the trains of thought familiar to us from waking life” (237). These things from my day, concerns I had for the next day, familiar people in forgein places were just endless symbols and representations that reflected a deeper reality (need to write this paper), transmuted to be acceptable to deal with in my dream. Every element of the dream had been coded in this way. Freud refers to these substitutions, everything that represents something else, as displacements. Everything has been substituted and changed in order to make it safe enough for us to digest while we are sleeping. Among these symbols, Freud argues that there is often one element in the sea of representations that is particularly difficult to reconcile. This is what he calls condensation (and what Lacan refers to as metaphor). It is the most important substitution, that must be protected at all costs, which organizes all of the other representations in the dream. “The entire mass of these dream thoughts is subject to the pressure of the dream work, and the pieces are whirled about, broken up, and pushed up against one another…”(237). Reflecting on my dream thoughts, I think the most important element of the dream is the blanket, which represents the work that I still have to do. The building, Kristiana, and the bathroom stall were all displacements. Freud would probably like to psychoanalyze further, what does that blanket represent from my childhood? I will spare you on this account.

To sum it all up in a blanket statement: our unconscious surfaces in symbols and representations in our dreams and we have to do work to decipher them; to uncover what we are unconsciously trying so hard to protect.

M. Jimmie Killingsworth and Jacqueline S. Palmer, “The Discourse of ‘Environmentalist Hysteria’,” Quarterly Journal of Speech 81 (1995): 1-19.

Killingsworth and Palmer explore the charge of “environmental hysteria”, a term often used by opponents in the environmental debate. They argue that most people agree that our environment should be “fit for life, not only for the present, but also for future generations” (1). But this idea of environmentalism is broad and abstract; it is an easy vision to agree with, but much more complex and dirty to unpack. Environmental activists like Rachel Carson (Silent Spring) claim there is more at stake than the “preservation of wild nature...people are directly affected” (1). This shifts the environmental conversation from nature to people, which explodes into a multitude of concerns from public health to human values. In this arena, activists challenge the direction of technological development and “improvements” from which our ever-growing capitalist society is based. This disturbance is upsetting to their opponents.

The use of “environmental hysteria” by environmental opponents, positing environmentalists as overly emotional and irrational, represents an attempt to “defuse the threat and maintain the stability of the social order as it is” (2). Killingsworth and Palmer argue that the charge of hysteria contains a measure of defensiveness, worry, and pathos that are worth exploring to better understand the public debate over environmental degradation (2).

“Hysteria” has a dark and deeply sexist history. Initially, only women were diagnosed with hysteria, believed to be “caused by the movements of the empty and dissatisfied womb” (3). According to Freud, hysteria occurred when repressed information appeared in coded expressions and often in physical symptoms (2). He found that traditional medicine was not helpful to cure hysteria. In fact, several doctors were baffled by the symptoms, not understanding the mental and emotional factors that brought physical ailments to the body. Killingsworth and Palmer return to this idea with their comparison of static and dynamic objectivity. Static objectivity ignores the sense of self and separates the mind and body, eliminating emotion and other subjective connections, whereas dynamic objectivity relies on the connectivity of holistic systems (10).

Freud acknowledged the power of words that could help the hysteric conceptualize/reconceptualize what their bodies are trying so hard to repress. The analyst, “by breaking the code and allowing the repressed information to enter into conscious conversation, could effect a talking cure that eliminated the bodily symptoms” (2). In this regard, environmentalists and nature writers like Carson are voices for the earth; they shed light on the signs of dead skin and weeping trees on the landscape; our collective repression bubbling up through the cracks, harming mother earth’s body. This activism pushes forward what we have turned away from for so long. Repressing the consequences of technological man has created an unsustainable disconnect between mind and body, humans and nature. “An ostensibly rational public discourse has neglected the signs of trouble for so long that only a cry of pain can break the public habit of inattention” (3).

By looking at hysteria in the environmental movement we can better conceptualize things like climate denial. Freud argues that, at first, we try to turn away from painful or challenging memories. We bury them deep within the earth and avert our attention from them. But “what is repressed returns to haunt the body” (5). This insistence in turning away explains why the climate denier cannot interpret the sights, sounds, and smells that show the earth is ailing. This only gets worse, as the “ego attempts to carry out its conscious purposes in life, the unconscious exacts a toll, which becomes larger and larger as long as the affect remains unsatisfied, eventually blocking purposeful action altogether” (4). But there is a silver lining: if hysteria can be talked through and satisfied, could a similar approach be used in the environmental movement to release the unconscious? Can we collectively overcome our initial powerlessness to reconstruct the demon we have created, and accept it as our own creation?

Carson’s work to bring ordinary people into consciousness and action is an attempt to “reintegrate the human mind with the natural body” (14). Just as the body and the mind are connected, so are humans to nature (humans are nature, a part of a larger nuanced system). This idea parallels Freud’s understanding that “the mind and the world have a more dynamic relationship than positivist medical science can allow”. Just as early hysteria was largely seen as woman’s emotional fabrication, we have a convenient division of mind and body in the environmental movements that permits “defensive practitioners of science to protect themselves against their powerlessness to understand or to cure by placing the blame on the ill by saying, ‘it’s all in your head’” (12).

Connection between the readings

The connection between the Freud and the Killingsworth and Palmer is that we are applying similar tactics from the interpretation of dreams to discourse and public text, as if they were dreams. “Dream work” that unearths the unconscious is similar to the work that activists do in their attempts to bring society into consciousness. Carson’s idea of this holistic and immediate connectedness with the earth is like Freud’s primary identification. In this primal connectedness, the infantile subject is translated into the social domain where the body of the mother is the body of the earth. Our connection to the earth is what we are trying to get back to, just as we are trying to recuperate for our separation from the breast.

Burke’s theory of identification greatly applies to the environmental movement, which both benefits from and is complicated by identifications. An issue like climate change is splattered across social, economic, environmental, and political discourses that are littered with thick group formations and lingering ideologies and suggestions. His urge to distance ourselves from identifications, to look critically at the sense of connectedness between people and ideas, provides a glimmer of hope that climate-deniers are capable of stepping back and considering their position. However, Freud’s idea that “persuadability operates irrepressibly and below the radar of critical faculties,” if true, does not bode well for the environmental movement. Even if activists like Carson raise the flag of awareness, Burke argued that if our identifications are not checked that too much identification will lead to war. In this case, war amongst ourselves and war upon the earth (i.e. war against ourselves).

Centering Rhetoric

Rhetoric resonates through the readings this week as we dive into questions of right and wrong that pollute the political landscape in which “rhetoric has traditionally been understood as a productive art enabling ethical and political action” (1). For Burke, rhetoric’s basic function is persuasion, but notes that any persuasive act is first an identifying act: “You persuade a man (sic) only insofar as your can talk his language by speech, gesture, tonality, order, image, attitude, idea, identifying your ways with his” (Davis, 125). In this understanding, rhetoric is used not necessarily to win an argument but to make a connection with the “other”. Burke argues that rhetoric is necessary as a mediatory ground to establish identification between two unlike individuals (Davis, 125-126).

Freud’s work demonstrates an “ancient rhetoric that involves not an emotional appeal but an immediate affection” (Davis, 142). We can see this in his description of primary identification. (It is also worth noting the comparison between Freud’s condensation and displacement and Foucault’s resemblances--types of rhetorical tropes like metaphor and analogy).

Davis argues that suggestibility and persuasion are not simply rhetoric’s fundamental aim but also rhetorical theory’s greatest problem because it “undercuts any theory of relationality grounded in representation, and therefore any hope of securing a crucial distance between self and other through reasoned critique or other forms of symbolic action” (142).

For Killingsworth and Palmer, the rhetorical analyst is “ever blocked by the presence of the political opponent, who demands to be given a voice and engaged (15-16). They point out that behind activism lies a desire for the death of the political opponent; a post-political world.

Thus, there is a reactionary rhetorical response to this death wish that undermines efforts to make the world a better place and creates an endless cycle of rhetoric. Rhetoric is both the solution and the biggest challenge facing the environmental movement.

Discussion questions:

- How do these ideas frame the current environmental debate? What rhetorical strategies do competing groups use and why or why not are those effective?

- What sorts of symbols of the earth’s ailment do you recognize? What are anti-environmental responses to these ailments? How would Freud describe their reaction to them?

- Do you align more with Burke’s theory that we are all separate and then form our ego or Freud’s theory of primary identification (ego forms directly and immediately)?

- Burke -- how can we feasibly step back and decide what is good or bad identification?

- Considering its deeply sexist history, should we use the term hysteria anymore? Is this a productive analytic?

- If Burke can interpret Freud as talking about the social rather than sexuality, then can we do the same thing with hysteria?

Part 2: Signifier / Letter

- Jean-Luc Nancy and Phillipe Lacoue-Labarthe, “The Logic of the Signifier” in The Title of the Letter: A Reading of Lacan, 27-86.

- Jacques Lacan, “The Instance of the Letter in the Unconscious, or Reason since Freud,” in Écrits, 412-444.

- Bruce Fink, “Reading ‘The Instance of the Letter in the Unconscious’,” Lacan to the Letter: Reading Écrits Closely, 63-105.

- Jacques Lacan, “Seminar on The Purloined Letter,” in Écrits, 6-50.

- Shoshana Felman, Jacques Lacan and the Adventures of Insight

Introduction

This section of reading is structured in two parts. The first looks at Lacan’s “The Instance of the Letter in the Unconscious, or Reason since Freud,” and the second examines his “Seminar on The Purloined Letter.” The first group of papers lay out, in great abstraction, the definition of the letter, the primacy of the signifier over the signified—and even the sign itself—and the structure of the unconscious. The second group of papers provide a psycho-anlaytic reading of the purloined letter. I believe that in order to best understand Lacan, the first readings should be treated as a singular unit. I will put them in a singular dialogue as they tend to explain each other far more than they explain themselves. Felman is much kinder to our vocabulary and provides an application to the abstraction.

Jean-Luc Nancy and Phillipe Lacoue-Labarthe, “The Logic of the Signifier” in The Title of the Letter: A Reading of Lacan, 27-86.

Nancy and Lacoue-Labarthe have provided a reading of Lacan’s “The instance of the Letter in the Unconscious, or Reason since Freud.” As Fink points out, deciphering Lacan is an act of analysis in of itself. Like all great scientists, the authors begin with the twofold definition which isn’t really a twofold definition of the letter:

- It designates the structure of language that contains the subject, meaning:

- The Letter is a material object that any subject and language relies on.

- The subject must use the letter to locate themselves and others, but is already pre-located by the letter’s structuring of the language.

- It constructs the subject and therefore “enslaves” the subject to its own structures (Language).

They end by reinforcing Lacan’s appeal to treat linguistics as a specific science (like Saussure) so that the theory of the subject can have “no relation to any anthropology or psychology to this “emergence” of linguistics…”(32.) Fink, points out that this is likely an attempt to avoid misinterpretation.

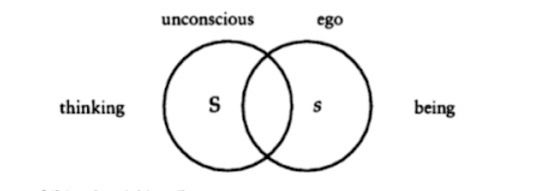

The second section of the paper concerns itself with Lacan’s famous algorithm; Ss. This is closely related to Saussre’s presentation of the sign

with some crucial adjustments. First, the big-S in Lacan’s algorithm represents the big signifier, which is always over the small-s signified. Second, there is no oval. Lacan does not believe in a unified sign. Third, there are no arrows, the signifier and signified are not constantly interchanging, in fact they are independent of one another. Finally, the bar cements the primacy of the signifier and irreconcilably divides the two.

The primacy of the signifier is the key point here.As Nancy and Lacoue-Labarthe point out, “All “evil,” in other words, comes from having conceived language in relation to the thing.” (Nancy 37) In other other words, “the signifier does not serve the function of representing the signified.”(Fink 81) In other3 words, language does not express human thought or the signified, it controls it.

Nancy then elaborates on Lacan’s examples. First, he presents Two doors, with the signifiers “Gentlemen” and “Ladies” above the bar. To Lacan, the signified in both pictures is the exact same. It is the signifier that alters and controls the sign. The second example involves a boy and a girl on a train who see “Gentlemen” and “Ladies” outside different windows and because they sit across an aisle, assume that they are physically at “ladies” and “gentlemen” respectively. A fight ensues. Nancy explains, that using a gender binary to differentiate between the two places is the act that makes gender binary.

Next is a discussion of the technical aspects of the signifier. The signifier is the prime variable of the algorithm (Ss) and the algorithm has “no meaning” without the signifer.

The third chapter explains “The tree of the signifier.” They begin by saying that the structure of the signifier is articulated. This has two meanings:

- It allows for φώνη to be constructed of signifiers of letters of phonemes.

- It allows for signifiers to chain together to create meaning.

Importantly, neither the phonemes or the chains of signifiers make meaning. Instead they always anticipate… meaning. We anticipate the endings of sentences to understand their beginnings. This anticipation is itself indicative of the way the signified “slides” under the signifier. As we assemble greater chains of signifiers, the signified become retroactively tied to the earlier signifiers. Simultaneously these connections disappear as quickly as they are formed. This retroactive meaning making is in direct opposition to the idea that language is linear in our experience and comprehension of it. This section ends with a discussion of poetry’s ability to engage with multiple meanings that are continually working in counterpoint with one another as a subject interacts with any chain of signifiers.

Finally, Nancy and Lacoue-Labarthe address “signifiance.”I think Fink’s diversion to metaphor and metonymy is a better direction. As Fink points out, signifiers can say the opposite of what their traditionally linked signified can express. By replacing one signifier for another (e.g “Stink Contest” for “election”, “Muenster” for “Minister”), we can speak about both appetizers and politics. This intentional sliding of the signified helps obscure meaning to some and deepen that same meaning to others.Metonym, Fink and Lacan point out, is the way in which we find substitutes for the Father.

Bruce Fink, “Reading ‘The Instance of the Letter in the Unconscious’,” Lacan to the Letter: Reading Écrits Closely, 63-105.

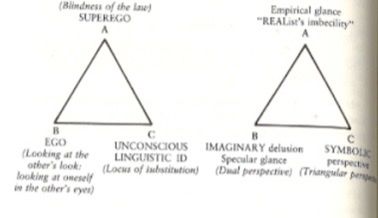

Metaphor as Fink explains it, is where meaning is produced in non meaning. An staunch presentation on psychoanalysis cannot literally be a breath of fresh air on a snowy Thursday, but nevertheless, here we are, soaking it in. These impossibly related words should mean nothing together, but somehow they do. With this in mind, we can return to Signifiance. Signifiance “is the operation of the signifier when it has passed over to the signified.” (E. 510) Fink reduces this multipage definition to the translation: Signifierness. Finally, all three readings define the topography of the unconscious. Nancy and Lacoue-Labarthe remind us that signification exists outside the subject but simultaneously was introduced as its internal structure. To resolve this contradiction, they explain that “the signifier represents the subject for another signifier and the subject is not able to represent anything but for another signifier.”(Nancy, 69) In other4 words, “When I speak of myself, I am presumably the subject of the signifier, whereas the person of whom I speak is presumably the subject of the signified.” (Fink 102) The answer, Fink explains looks like the following diagram:

Here, the unconscious and the ego do not overlap. To work with the ego is to work with the signified, and the unconscious, which is what Lacan cares about in this paper exists in the realm of signifier. It is then the job of the analyst to listen to the metonyms and metaphors of the analysand to understand the workings of the unconscious, and thus cure it.

Shoshana Felman, Jacques Lacan and the Adventure of Insight

Felman’s paper discusses Lacan’s famous “Purloined Letter” paper. Here, Felman explains that Lacan’s theory of signification can be used as a hermeneutic reading strategy. Thus, Felman teaches us how to read the reading. She explains the theory, then looks at Lacan’s use of the theory in explaining the “Purloined letter.”

First, she explains the theory. The analyst is expected to read past the literal meaning of the patient. Mixed metaphors, pauses, interruptions, anagrams of words in different languages all hint at the underlying unconscious. Felman also turns this strategy upon itself. As I read, your interpretation of this reading is affected by your unconscious, and you become both an analyst and your own analysand. To Felman, this realization—first discovered by Freud—is revolutionary for three reasons. First, the act of reading does not reveal oneself through resemblance, but difference. Second, this reading is constructed in dialogue between the analyst and their own unconscious. Finally, the unconscious is constructed, not discovered, and it is constructed to explain “the efficiency of the practice.”(Felman 24)

Next, Felman turns from Freud to Lacan. She begins by situating Poe in the western canon of poetry. She argues that his poetry is the outgrowth of his psyche, but Poe himself is a psyche constructed by poetry. She explains that Poe is one of the most written about poets in psychoanalysis, because he is both lauded and hated. He is influential enough to be frequently written about, even by his major detractors, and thus is ideal for this type of psychoanalytic reading.

Felman then expands on some less than amazing analyses by Joseph Wood Krutch and Marie Bonaparte. Krutch believes that Poe is just transcribing severe neurosis. (Felman 32) Felman responds by pointing out that Krutch is overly reductive. She then questions Krutch’s own neurosis, something that he seems to ignore. She then brings up Marie Bonaparte’s work. Felman points out the Bonaparte is much more sympathetic to Poe as a human being, but still seeks to diagnose him through his art. Felman reiterates that this approach confuses poetry with mental illness, it does not analyze literature so much as author and it does not explain Poe’s “genius.”

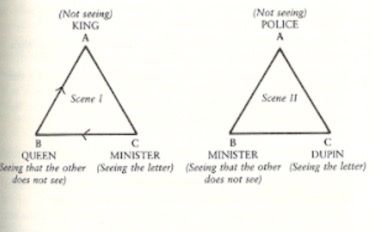

Now Felman begins looking at how Lacan chooses to analyze “The Purloined Letter.” Quick Summary:

A queen gets a compromising letter and hides it from her husband by making it look like a normal letter. It gets stolen from right in front of her by a minister, but she can say nothing because it might alert the king. She then directs the police to take the letter back but they are unable to find it. A detective, Dupin, retrieves the letter by finding it crumpled under the minister’s desk, where it was hiding in plain sight, and replacing it with a decoy.

Lacan takes this story to be a tale of repetition compulsion. She provides the following diagram to explain the repetition:

Lacan does not examine this structure much deeper, but Felman points to multiple triads this diagram maps onto:

We can discuss these diagrams in relationship to the previous presentation, but importantly, Lacan feels that the physical letter, is a signifier without a signified. We know nothing of what it says, and thus cannot know its meaning, but we can see possible significations. Lacan sees it as a signifier of the repressed which keeps trying to emerge within the story.

That said, the scenes do differ. Felman points out that this scene can be read as an allegory for psychoanalysis. Dupin, who worked as the unconscious, is able to see the letter and replace it with a harmless substitute. One signifier becomes another. This differs from Bonaparte in 5 major ways:

- It interprets the difference of the characters and not their reflection of the same author.

- It analyzes the signifier of the letter and not the signified. It does not care about the content of the letter.

- It considers the text and not the biography.

- It considers the analyst of the text as a possible analysand.

- It looks at the inter implications of art and psychoanalysis and not the application of one to another.

Felman finishes her essay by pointing out that psychoanalysis can be used as a tool for reading with multiple outcomes. The How to use psychoanalysis is itself a psychoanalytic question. Poetry and the unconscious both resist the want to be psychoanalytically interpreted, and exist because of psychoanalytic effects.

Connecting the Readings

Lacan is obviously the central point to all of the readings, which are themselves guides for reading Lacan. The major theme and the one most important for our understanding of rhetoric is the importance of the signifier outside of the sign itself. Here, the signifier becomes responsible for signification. The readings also build from one to another. After Fink, Nancy, Lacoue-Labarthe, and Lacan’s exhaustive explanation of the signifier, Felman takes an opportunity to show its rhetorical power.

Centering Rhetoric

Signification and Letters give us a new way to understand signs and sign theory. This methodology transcends the arbitrary nature of the sign, and instead points to how powerful observing connections between signs through signifiers can be. This act is a rhetorical strategy involving a special type of hermeneutic reading. It finds meaning through careful examination of metonymy and metaphor. This method helps us track the propagation of signs and the work they do in the world.

Importantly, while the signifiers and signs in Lacanian psychoanalysis are rhetorical, its important that we consider one of Felman’s implications: rhetoric is inherently psychoanalytical. The choices we make in writing, understanding, and communicating are all processed through the letters of the unconscious. The psychoanalytic method in many ways demands that we turn it upon ourselves.

Discussion Questions:

- How does using mathematical structures effect Lacan’s argument? Is it a useful tool in rhetorical research?

- Much like we have to question what is rhetorical, what is or is not psychoanalytic?

- Where is meaning in psychoanalysis? Is it in the mind, the body, the aether?

Bibliography

Lakoff, George, and Mark Johnson. Metaphors We Live By. University of Chicago Press, 2008.

Kuehne, Tobias. “Mathemes Avant La Lettre: Lacan’s Language Functions in ‘The Instance of the Letter’ as Triggers for Formalization.” Paragraph 40, no. 2 (May 19, 2017): 193–210.

Brodsky, Seth. From 1989, or European Music and the Modernist Unconscious. Univ of California Press, 2017.

Part 3: Applications of the Signifier

For applications of the method of reading at the level of the signifier, I turn to three examples of reading American presidents and the American presidency through the lens of psychoanalysis. Each of these authors finds the signifier in a different place, however: Copjec and Rubenstein locate the signifier in the speech about and representations of presidents like Ronald Reagan, who mean more than they say. Silverman attends to the Statue of Liberty and many ways it figures identity. Admittedly, Rubenstein turns to Baudrillard rather than Lacan primarily, but in service of the argument that the relationships of the signifier as the central feature of the reading.

Joan Copjec, Read My Desire: Lacan Against the Historicists

“The Unvermogender Other” opens with a description of the ‘realist imbecility’ of the television news cameras in their coverage of Reagan’s presidency. As the story goes, the news placed Reagan’s speeches side-by-side to show how he had contradicted himself and failed to keep his promises to the public. But the fact that Reagan had lied wasn’t enough to turn the public against him. News broadcasters confused the ‘referent’ with the ‘signified’: as they tried to get the public to recognize the literal, constated falsehood of Reagan’s speech, they failed to attend to “the dimension of intersubjective truth,” or the particular investment the public had in Reagan. Copjec’s illustration makes two important points: first, that within democracy, it is possible for obvious contradictions between what the public knows and what it feels to be true can be stably maintained. Second, that this contradiction, even at the level of the sign, takes the form of a split between the universal statement (or here, referent) and the particular enunciation (or signified). The referent gives rise to the illusion that reality is “free standing, … independent of and prior to any statements one can make about it.” The signified, however, describes the particular investment in Reagan, the way in which what Reagan’s relationship to the public was captured in an economy of love in which “it is still possible to dislike the gifts, to find fault with the other’s manifestations, and still love the other.” (143) What Reagan’s words meant was, in other words, irreducibly singular. Regardless of how false his statements were within a general domain of reference, America’s hysterical romance with Reagan shows us that whatever Reagan gave to us would have been enough:

If all our citizens can be said to be Americans, this is not because we share any positive characteristics but rather because we have all been given the right to shed these characteristics, to present ourselves as disembodied before the law. I divest myself of my positive identity, therefore I am a citizen. … Reagan … became the emblematic repository, the most visible beneficiary of this increase of belief that beyond all its diverse and dubious statements there exists a precious, universal, “innocent” instance in which we can all recognize ourselves. (146)

Being misrecognized allows the democratic subject to become reinvested in the need to be recognized by the Other. Copjec writes that “the subject of democracy is thus constantly hystericized, divided between the signifiers that seek to name it and the enigma that refuses to be recognized.” (150) This is the ‘realist imbecility’ of the demos: When our particular signifieds go unacknowledged, the referent, or the abstract polity, stands in as a promise of our eventual recognition. Copjec also leverages ‘realist imbecility’ as a critique of Foucault, for whom power belongs properly to no one, and is instead distributed across a field of discourse. For Foucault, power is a form of relation between bodies, and cannot be reduced to the particular motives or identities of the bodies who exercise it. But according to Copjec, Foucault inhabits the position of the universal: the position in which an abstract subject becomes power’s point of application as the universal addressee of the law. In modern democracies, transgressing the law is retroactively constituted as a gateway to a prohibited pleasure. The proliferation of the law’s forms therefore act as a multiplication of these prohibitions even as it appears to extend principles such as ‘liberty’ or ‘equality’.

Diane Rubenstein, This is Not a President: Sense, Nonsense and the Political Imaginary

Rubenstein argues that we can “read the history of the twentieth century American presidents as a gradual loosening of the signifier from the signified.” (Rubenstein 2008, 31) Her account of Ronald Reagan, for instance, describes him as the man who became an actor who became a president; a political role in which he ‘played’ himself. As Rubenstein writes, Reagan came back “as a double of a self that never was,” a stage name that is his real name, a “Reagan that resembles himself.” (28) Discerning between the ‘real’ and ‘fake’ Reagan was always unclear because Reagan was pure copy: “It was the role of a lifetime: himself!” (12) “Reagan” is a signifier, a name that becomes meaningful only through a successive splitting of the man from himself. Rubenstein also cautions critics that framing secrecy as a hermeneutical problem, one in which the question is of how to interpret the speech that is being delivered to us, “presupposes a theory of readability in the text.” This means that the critic’s strategies of reading are presumptively anterior to the text, inhabiting the document, sign, or testimony. Such assumptions dispose the critic to assume that the text is coherent before they come to it, and that what has been said is predisposed to make sense.

Rubenstein also uses Baudrillard’s neologism of hyperreality to frame the Reagan presidency as an era whose dominant feature was the confusion of textual original and copy. Hyperreality is a state of artificial naturalness created by substituting the original with a miniaturized model. The “territory no longer precedes the map, but is generated by it,” as when a photograph becomes more ‘real’ than the scene from which it was taken. This logic also works upon speech, where the duplicated, miniaturized, and reproduced version of an original text becomes more ‘real’ than that archival original. The point of this substitution, however, is that it troubles the very notion of originality, achieving an absence of historical depth. The simulation presents itself as a pure surface, disconnected from its history.

Applied to the presidency, this confusion ultimately undermines the possibility of discovering a real ‘self’ beneath or behind the executive’s representation. Rubenstein, for instance, draws attention to how after his film career, Reagan received his ‘original’ name as a stage name. He came back “as a double of a self that never was,” a stage name that is his real name, a “Reagan that resembles himself.” Discerning between the ‘real’ and ‘fake’ Reagan was always unclear because Reagan was pure copy: “It was the role of a lifetime: himself!” The theory of the president-as-simulacrum troubles the possibility of locating an ‘original’ or ‘authentic’ signified for the president or his appeals. It also enables a reading of what Rubenstein calls the sign’s ‘obtuse meaning’: the “instances in which we have a signifier but no signified.” If the sign no longer represents or references, we may instead turn to the form of representation, to a critically reconstituted relationship between signifiers. In Rubenstein’s words, we must locate the “figural subtext whose rich metaphoricity suggests something beyond representation.”

Kaja Silverman, “Liberty, Maternity, Commodification”

Silverman offers the following, somewhat traditional, semiotic reading of the Statue of Liberty by referencing other, related signs, most notably Delacroix’s Liberty Guiding the People to the Barricades (1830). In this case, the sign of the painting/statue/artwork is set aside for an emphasis upon the particular signifiers (costuming, the body) that are foregrounded by each.

[W]hereas Delacroix’s Liberty carries a tricolour and a rifle, and is in fact leading a revolutionary insurrection, Bartholdi’s Liberty supports a domesticated torch, and holds a stone tablet with the date of a revolution long past. Liberty Guiding the People also strides robustly forward, trampling bodies under foot, accompanied by armed comrades and the smoke of battle, whereas her subsequent counterpart stands solitary and motionless, with only her right foot suggesting even the possibility of movement. However, what speaks most eloquently to the distance separating the moderate republicanism articulated by Bartholdi’s statue from the radical republicanism embodied by Delacroix’s protagonist is that whereas the latter wears a red phrygian cap, the former displays a seven-rayed diadem, evocative of a sunburst. (72)

Silverman finds the costuming and body of each “Liberty” to be particularly significant. Whereas Delacroix depicts liberty in a red, “phyrygian cap” that recalls the caps “awarded to slaves who had been given their freedom,” Bartholdi’s Liberty wears a “radiant headdress” that carries “a monarchical past.” (73) Delacroix (and others) also depict Liberty as “breaking free from her loose garment, drawing a metaphysical connection between the political revolt of the people and the exposure of the sexualized parts of the female anatomy.” The American counterpart, meanwhile, “completely buries the female form beneath her classic drapery.” (74) As Silverman states, “What Bartholdi’s statue held out to his compatriots was the promise of a liberty uncontaminated by passion, a republic without republicanism, and a political arena from which the female body would be discretely barred.” (75)

The larger point made by the article regards the radical or revolutionary political potential encoded into representations of the female body. Silverman in particular draws upon the maternity/prostitution opposition in order to show how Bartholdi’s Liberty advances a more monarchic and conservative feminity on behalf of American national identity. It is not just that the statue advances a political desire, but an Oedipal one as well -- meaning a desire for the mother, and more specifically, “the desire to ‘return’ to the inside of the fantasmatic mother’s body without having to confront her sexuality in any way.” (82) As Silverman writes at length:

This maternal construction clearly taps into lack and Oedipal desire in a big way, but to say that is not the same thing as to propose a one-for-one relationship between Mme Bartholdi (or any other existential mother) and the Statue of Liberty. I would in fact go so far as to suggest that Bartholdi’s colossus works to rectify the political degradation … of the mother whose sexuality had been exposed within political representations like Delacroix’s Liberty, Daumier’s Republic, or -- to return to the example I cited a moment ago -- Courbet’s Origin of the World. (80)

Whereas the other artworks described trouble the mother/prostitute dyad by foregrounding the naked female form as a mode of political or revolutionary resistance, the covering-over of the body presents the opposite message; it is an either/or; and preferably the mother. As certain later historical and aesthetic accounts demonstrate, however, Liberty is not only a maternal figure:

‘This decent woman’ [Trachtenberg] writes, ‘takes on an altogether different character’ to those who ‘know’ her (and this ‘know’ has a decidedly carnal inflection) than to those who merely ‘see’ her from outside, since ‘for a fee she is open to all entry and exploration from below.’ The implication is obvious: although Liberty seems to be a mother, she is in fact a prostitute. (82)

According to Silverman, such renderings do “nothing to challenge the binarism of mother and prostitute; she has simply slipped irretrievably from the first of those categories to the second.” (85) If the purpose of the article is to highlight the symbolic exchange that characterizes the statue, then such exchange is possible “because her assigned gender makes her so pre-eminently exchangeable so easily transferable from France to England, from the Chrysler Building to the Empire State Building, and from buyers to sellers of all kinds.” (87-88)