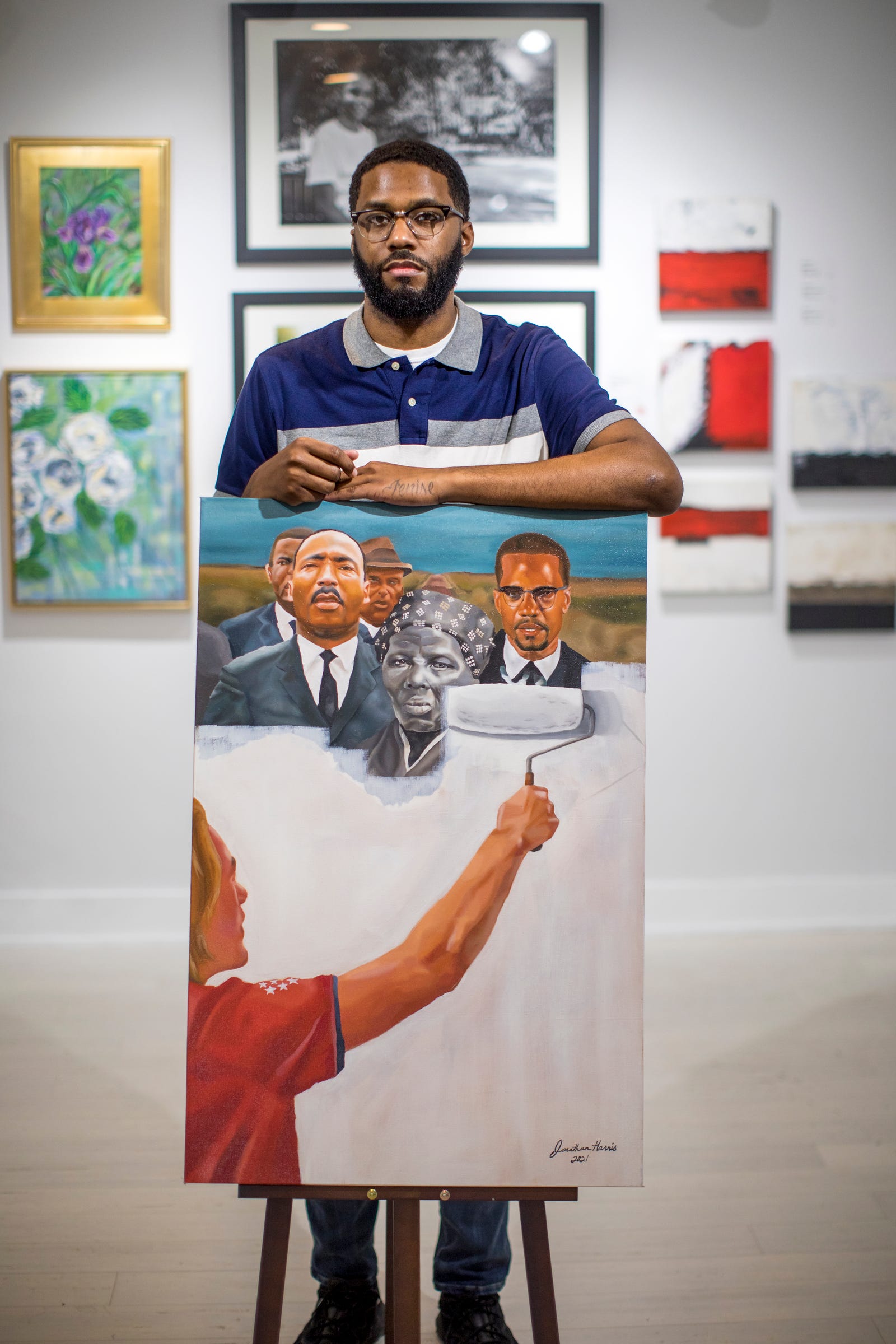

Erasure

Erasure describes an epistemology (a systematic theory of knowledge) whereby secrecy organizes knowledge by removing it from sight and displacing by palatable or recognizable narratives. For that reason, it resembles what Peter Galison calls anti-epistemology. Erasure adds two distinct features: removal and production, which correspond to the 'negative' and 'positive' aspects of erasure. Importantly, 'negative' and 'positive' do not refer to 'bad' and 'good' value judgments but rather to functions of addition and subtraction, whereby knowledge is either taken from public view or something is added to deflect attention from what has been removed. In the critical tradition of deconstruction, words under erasure are marked using strikethrough, which indicates an almost imperceptible, minimal difference. Erasure is an absence in the historical record. It is also the construction of a different, mythic narrative as a "cover-up" of the destruction wrought by imperialism and settler colonialism.

Paired Reading

Tzvetan Todorov, "The Semiotic Conquest of America"

Recordings for this Entry

- Erasure as Negativity (Audio Only)

- Erasure as Production (Audio Only)

This entry describes erasure in two ways: (1) as the removal or deletion of content and (2) as a form of production, a way of layering a new past over the one to be forgotten.

Erasure as Removal

As negativity or removal, erasure has connotations of iconoclasm, as well as the forgetting, disavowal, and concealment of content. The word erasure sometimes signifies iconoclasm, which means “the destruction of the symbol,” and which makes the sacred object into a profane thing. It may help to think of “negative erasure” as forgetting -- as it’s most commonly understood. As Bradford Vivian writes, forgetting is sometimes narrowly understood as negativity: for some scholars, it “ continues to signify a loss, absence, or lack -- not simply of memory but of live connections with a tangible past.” Forgetting can be the “opposite of memory" and “a symptom of the undesirable dissolution of communal heritage or historical wisdom.”

Erasure-as-removal is the idea that secrets exist because some piece of information is taken away from our view, such as by the government’s supposed management of secret information. It also describes knowledge in the fact that a public does (or publics do) not know this content. As Peter Galison explains, no one has any very good idea how many classified documents there are in the contemporary world. “No one did before the digital transformation of the late twentieth century, and now -- at least after 2001 -- even the old sampling methods are recognized to be nonsense in an age where documents multiply across secure networks like virtual weeds. … in the last few years [before 1999], the rate of classification increased fivefold, with no end in sight. Secret information is accumulating, at a rate that itself is accelerating, far quicker than it is being declassified.” Erasure in a negative sense is the removal of knowledge and the dangerous, conspicuous accumulation of this information.

In The Semiotic Conquest of America, Tzvetan Todorov writes that “the efficient conquest of information was always what brought about the downfall of the Aztec Empire.” The systematic elimination and replacement of Indigenous language by Cortes and European colonizers was a mode of removal because it meant the destruction of the historical record, forcing it into secrecy. Cortes was motivated “to control the information he received” both in order to eliminate the indigenous knowledge he encountered and to take advantage of “how others [namely Indigenous peoples] were going to perceive him.” The destruction of the archive is evident because Cortes understood the myth of Quetzalcoatl’s return -- and then positioned himself as its architect. For example, “the idea of identifying Cortes with Quetzalcoatl definitely existed in the year immediately after the conquest,” but not before. Negative erasure is the removal of myth, the removal of history from the indigenous inhabitants of the Americas; the destruction of this archive.

Erasure as Production

As opposed to negativity, erasure can be understood as the “positive” production of “forms,” which includes a range of terms including “patterns,” “practices,” “significations,” and “myths.” Unlike the iconoclasm of erasure-as-removal, erasure-as-production is a form of iconophilia; a 'love of the image' that proliferates or multiplies representations. To say that erasure is “positive” or “affirmative” or "productive" does NOT mean that it is ethically good or morally sound. Instead, it means that erasure is something brought forth into the world, rather than something that is withdrawn from it. It’s important not to confuse “positivity” with ‘good feelings” or “positive intentions.” Instead, erasure is a constructed, produced, or enacted form. It is new information or data that violently “over-writes” the past with a new (settler) narrative.

The production of erasure is a material and rhetorical process. By rhetorical, I mean that erasure is something that happens in and through discourse -- as speech, representation, performance, and practice. By material, I mean that it has bearing on something more than language: life, labor, and a set of real circumstances. As Patrick Wolfe writes in, “Settler Colonialism and the elimination of the Native,” “the logic of elimination marks a return whereby the native repressed continues to structure settler-colonial society.” Settler colonization [is] a structure rather than an event. That means that erasure is not *a* happening, a single obliterating instance in which the white colonizer commits genocide against and forces servitude upon indigenous and exogenous peoples. Instead, settler colonialism is a series of events weakly supported by a material rhetoric, one which creates the real with discourse.

In Todorov’s Semiotic Conquest of America, this kind of erasure is happening constantly. Cortes imposes himself as an agent of Mayan and Aztec myth, literally re-writing this history with himself and white settlers as agents. He did “everything in his power to reinforce” the myth that he and the Spanish colonizers embodied the coming of Quetzacoatl. The reason this chapter is important is that it draws attention to the way that Cortes literally deploys the white, western tradition of classical rhetoric as the dominant term in which this history can be told. Todorov, it should be noted, is complicit with Cortes. He argues at the end that without the Spaniards, the spread of Nahuatl would not have been possible. That is the erasure of the colonizer: one in which the colonizer’s history and intellectual traditions -- are spun as essential to the history and development of the colonized. That is also why the production of erasure is discursive and material violence -- it uses discourse to falsify, justify, and intellectualize genocidal violence as if it were a stage of indigenous cultural development. In fact, this is nothing more than a seizure of language that twists the communication gap between settlers and Indigenous peoples as into evidence that the latter cannot communicate.

That kind of erasure, in which an authoritative straight, heterosexual, and modern history is layered over top of an erased past, still happens today. In “Teaching Theory, Talking Community,” Joy James writes

“Philosophy or theory courses may emphasize logic and memorizing the history ‘Western’ philosophy rather than the activity of creating philosophies or theorizing. When the logic of propositions is the primary object of study how one argues becomes more important than for what one argues. The exercise of reason may take place within an illogical context -- in which academic canons absurdly claim universal supremacy derived from the hierarchal splintering of humanity into greater and lesser beings, or the European Enlightenment’s deification of scientific rationalism as the truly ‘valid’ approach to ‘Truth.’”

Ultimately, that is also what the story of Cortes as retold by Todorov does. Todorov, by refusing to question the classical tradition perpetuated by Cortez in the place of indigenous religion, tradition, language, and culture, instead affirms and validates these colonial intellectual traditions. The lecture The Semiotic Conquest of America, in other words, can’t see in itself the way that it perpetuates the same kind of linguistic and material violence.

Another present-day example of produced erasure occurs in the Netflix documentary Wild Wild Country. The documentary showcases the tenuous relationship between the townspeople of Antelope, OR, USA (about 50 or so) and a group of devotees to guru Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh (also commonly known as Osho) who moved into Antelope to establish a religious and cultural settlement. In the second episode, the former mayor of Antelope, Margaret Hill, says the following about Rajneesh’s followers. Hill’s speech is spliced together with testimony from other Antelope residents who support her statement.

“When they came to the community, they were welcomed to the community…but basically it wasn’t until they really started throwing their weight around…it’s not a pleasant experience at all.” … “Should some—a group of people of like persuasion be allowed to enter an area and literally wipe out the culture that is there?” … “One of the things that has—we have found most irritating is their habit of not really telling the truth. Even though you catch them in a lie, they very blandly act as if nothing happened.”

Margaret Hill and these other Antelope residents, who are white landowners and the descendents of colonizers to the Columbia Plateau in central Oregon, are without irony astonished that Osho’s adherents, a group of “people of like persuasion,” would settle an area with the goal of “literally wip[ing] out the culture” of the white settler inhabitants. The fact that she says this on lands stewarded by the Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation, the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, the Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs Reservation of Oregon, and the Nez Perce Tribe illustrates the power of erasure to cover up history. Specifically, the substitution of a narrative of white nativism, in which they are “indigenous” and at risk of being displaced, illustrates how erasure can produce white fragility, victimhood, and violence in the image of actual victims of settler colonial violence.

According to historian Richard Slotkin, the myth of the frontier” is “the conception of America as a wide-open land of unlimited opportunity for the strong, ambitious, self-reliant individual to thrust his way to the top.” What he calls “frontier psychology” which is motivated by this myth, describes murderous political violence done in the name of commerce. “The first colonists saw in America the opportunity to regenerate their fortunes, their spirits, and the power of their church and nation; but the means to that regeneration ultimately became the means of violence, and the myth of regeneration through violence became the structuring metaphor of the American experience.”

Erasure and Disavowal

The continual reliance on a mythic narrative that both recognizes the “existence of particular foundational traumas” and psychologically ‘rescues’ the perpetrators of settler-colonial violence -- and their descendants -- is what Lorenzo Veracini calls “disavowal”. The simple formula for disavowal is “I know very well, but nonetheless.” For instance, we may all know very well that consumer capitalism is destroying the earth’s environment, but purchase “greenwashed” products -- products marketed to be eco-friendly -- as a way to “rescue” ourselves from having perpetuated environmental pollution.

In the context of settler colonialism, disavowal is a defense mechanism of white fragility. It protects the colonizer from the truth of their own history by spinning a lie. When put together as a story or narrative, it is a way of turning the harm that the protagonist has done to others into the protagonist’s feeling of victimhood. For the colonizer and their descendants, disavowal is a way of saying “I know very well that my ancestors committed genocide, held deeply racist beliefs, and perpetuated institutions like slavery, but I will instead behave as though I am a victim and that the indigenous, Black, and brown people who my ancestors have literally attacked are responsible for white victimization. Like the example of greenwashed products, settler colonialism constructs a narrative in which the colonizer can be ‘more’ native than the indigenous that they displaced. By doing so the colonial ego refuses to confront its history while telling a story in which the colonist can be ‘rescued’ from the fact of the historical violence they have committed.

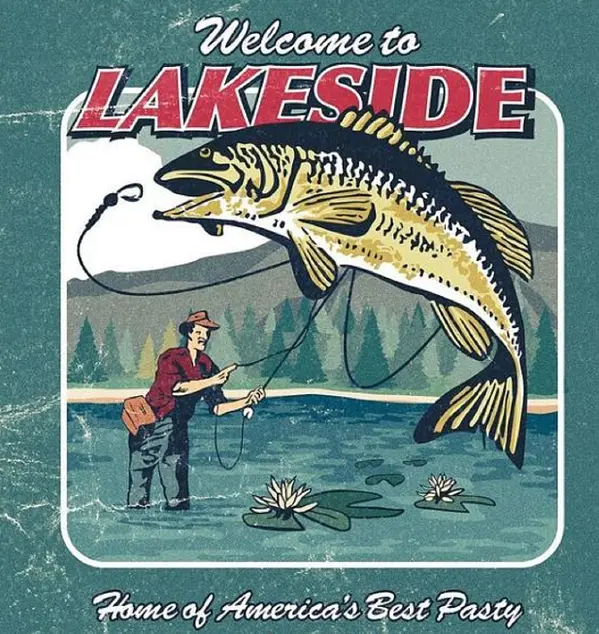

The last example for this recording comes from Season 3, Episode 2 of the television series American Gods. In this audio clip, the main character, “Mike,” (also “Shadow Moon,” played by Ricky Whittle) has arrived in the Wisconsin town of Lakeside, on the south shore of Lake Superior. Before the clip, the show makes a point to display the graphic violence of the colonizers against the indigenous inhabitants of this present-day town. The clip itself tells a settler-colonial story about Lakeside in which their “traditions” involve rituals of pollution, an embrace of so-called “nordic heritage,” myths about “first citizens” and traditions brought from “the old world.” In the background, there is music playing to the tune of “Always there to remind me.” The story that is layered over the indigenous story is erasure: one that creates the fiction of “nativism” for the colonizer’s guilty conscience.

Link to the audio file for "American Gods S3E2," transcript below.

Look at the beautiful clunker! Every year we take a wreck and we put it out on the lake and then folks guess the date and the time when it’ll break through the ice come spring. And then the winner splits the pot with the high school. It’s really fun! You’re gonna love it. Now, while Lakeside is known for its fishing, its the to-die-for pasties that put us on the map. Every delicious bite is like a warm hug. But you know what really makes this place special? The people. Everyone here genuinely cares for their neighbor. It's in everything we do. This spirit was passed down to us by the town’s first citizen, and benefactor Lester Hamilton. And when he died, he left Lakeside his fortune so that its citizens would continue to prosper. All that he asked in return is that we honor some of his favorite old-world traditions. So every year we hold an ice festival to celebrate his generosity and give thanks for our magical little town and its nordic heritage.

Additional Readings

UnTextbook Chapters

- The UnTextbook, "The Settler Situation"

News Releases and Editorials

- Sam Adler-Bell, "Behind the Critical Race Theory Crackdown," African American Policy Forum January 13, 2022.

Academic Articles and Chapters

- Alessandra Raengo, "Introduction" to Critical Race Theory and Bamboozled

- Adrienne Mayor, "Suppression of Indigenous Fossil Knowledge"

- Nikki Sanchez, "Decolonization is for Everyone"

- Indigenous Action, "Accomplices, Not Allies"

- Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang, "Decolonization is Not a Metaphor"

- Lorenzo Veracini, "Settler Collective, Founding Violence, and Disavowal: The Settler Colonial Situation"

- Sarah Bond, "This is NOT Sparta"

To Cite This Page

- Atilla Hallsby (2022), "Erasure" in The UnTextbook of Rhetorical Theory: The Rhetoric of Secrecy and Surveillance. https://the-un-textbook.ghost.io/secrecy-and-surveillance-erasure/. Last Accessed (Day Month Year).